Britain and Greece’s Parthenon Dispute

Photos by Forrest Anderson

Those Lord Elgins! What are the chances that a father and his son would be considered responsible for carting away some of the most iconic cultural treasures of two ancient nations? Their story is even more bizarre because neither of them set out to do so, lending credence to the saying that the British conquered the world by accident.

The 7th Earl of Elgin’s and later his son the 8th Earl’s conduct have sparked heated international debates for more than 200 years that persist today.

The 7th Earl, Thomas Bruce, was the ambassador to Constantinople in the 1810s when he had about half of the surviving sculptures on the Parthenon in Athens, Greece hacked off, crated up and shipped off to Britain. Honestly, who does that?

His son James Bruce, the 8th Earl of Elgin, commanded a British army that invaded Beijing in 1860 because the Chinese government tried to stop the British from selling Indian opium in China. When the Chinese threw his army’s advance party into prison and killed and tortured some of them, the Earl ordered the Chinese emperor’s exquisite summer palace, the Yuanmingyuan, burned and looted. Again, ships filled with crates of treasures sailed off to Europe to enter palaces, private collections and museums where many remain.

The 8th Earl’s adventures were partially chronicled earlier on this blog. This blog entry largely concentrates on Britain’s 200-year conflict with Greece over the fate of the Parthenon marbles, which rose to the fore again earlier this year when Greek President Prokopis Pavlopoulos asked visiting British Prince Charles to return the marbles to Greece.

Charles, who has no authority to return the marbles since doing so would take an act of the British Parliament, responded, “We are all Greeks,” a quote from the English poet Percy Shelley meaning that laws, literature, religion and arts have their roots in Greece.

His comment was a thumbnail summary of the British argument for keeping the Elgin marbles, that the marbles are part of mankind’s cultural heritage and the Greek government, which came into being after Elgin took off with the marbles, is not their legal owner.

The dispute goes to the heart of what major cultural icons mean in the context of both nationalism and globalization and how their ownership should be handled in a world in which treasures have changed hands as often as people have gone to war, governments have risen and fallen, and borders have changed.

We’ve been this way before. The building of the Parthenon (447-432 B.C) happened because the Persian empire’s army had razed an older temple on the site while invading Greece. Greece won that round. The Parthenon was built as a temple to Athens’ patron goddess and war diety, Athena, to celebrate and thank the gods for the victory and independence over the imperial invaders. The marble sculptures, considered the finest in Greek art, were created under the supervision of the great architect and sculptor Phidias.

The building is the most important surviving building of classical Greece. You can’t get better than the Parthenon as a symbol of Greek nationalism. However, the Parthenon is also the iconic symbol of democracy in Athens, which is considered the root of the Western democratic tradition which has since spread globally. Athena’s status as a goddess of reason and wisdom mades her a universal symbol. In later centuries, when Greece was absorbed into the Roman Empire, the Romans adopted Athena as the goddess Minerva and took her throughout the empire, including to Britain. The 7th Earl of Elgin called the Parthenon the Temple of Minerva and clearly considered her legacy part of the British empire’s. It is this broader cultural heritage that is celebrated at the British Museum, where the marbles are viewed along with Roman, Egyptian, Persian and other artifacts. As British Museum officials are fond of pointing out, the marbles are seen by 6 million visitors annually, as compared to 1.5 million who visit the Parthenon itself.

What are the marbles?

The Parthenon stands on a three-step platform, its roof supported by a post and lintel structure, with eight columns on either end and seventeen on the sides. At either end is a double row of columns. The gables on either side had a triangular pediment that originally had sculpted figures. The building also had sculptured friezes of carved pictorial panels. The temple is famous for its Doric columns that have the appearance of being straight from a distance while they actually lean slightly in and are slightly curved.

A model of the Parthenon, British Museum.

Most of the surviving sculptures that were on the building are in the British Museum or the Acropolis Museum in Athens, with a few in the Louvre in Paris and in museums in Rome, Vienna and elsewhere in Europe.

The building originally had 92 metopes, or square panels, on the frieze. It was a monument to war. Those on the east depict a mythical battle between the Olympian gods and giants for control of the cosmos. Those on the west show a mythic battle between Athenians and Amazons, a nation of all-female warriors. The southern ones show a battle of the legendary Lapiths against half-man, half-horse centaurs. Those on the north side are poorly preserved but appear to depict the sack of the city of Troy.

Panel showing a centaur battle, British Museum.

A frieze around the exterior walls of the inside “cella” structure of the Parthenon depicts a procession that some believe was an annual one to honor Athena and offer sacrifices and a new dress to her. A bas-relief frieze running around the exterior walls of the cella was carved in situ. Some interpret it as mythical pre- and post-battle processions.

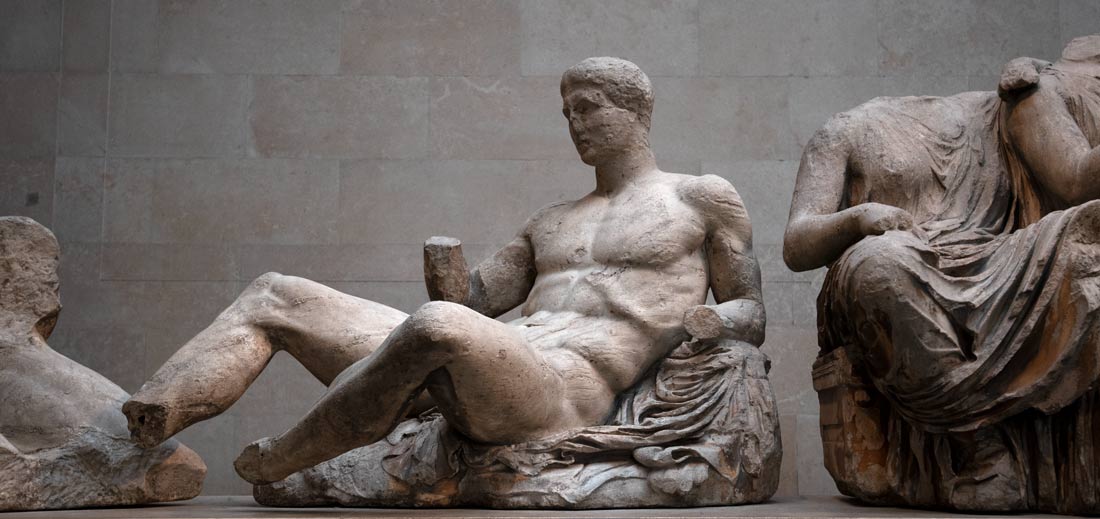

The figures on the triangular east pediment depict the passage of the day, with the horses of the god of the sun, Helios, ascending into the sky at the start of the day and the moon goddess Selene’s horses as the day ends.

Selene's horse, British Museum.

Various figures on the pediment are dieties and a mythical king and his daughters.The largest figure, the god Poseidon, was broken in 1688 by the Venetian assault. Venetian troops looted the building. While they were trying to remove Athena’s and Poseidon’s horses and chariots from the pediment, the sculptures fell and were smashed. Parts of Poseidon are in the British Museum and the Acropolis Museum.

The Parthenon’s roof and much of the sanctuary interior was destroyed in a 3rd century fire. Not long after, Heruli (East Germanic) pirates sacked the city and destroyed the Parthenon and other public buildings. Repairs were made in the 4th century. The Parthenon was a temple to Athena for almost 1,000 years until it and other pagan (i.e. polytheistic) temples were ordered closed by the Eastern Roman Emperor. The statue of Athena was taken to Contantinople and later destroyed, possibly when the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople in 1204.The Parthenon became the Church of the Parthenos Mary in the late sixth century, converted to a Christian Church with an alter and walls painted with Christian icons. Christian instructions were carved into the columns. Some sculptures were removed while others were re-interpreted with a Christian theme. The building became one of the most important Christian pilgrimage destinations in the East Roman Empire. For about 250 years, it was a Roman Catholic church with a bell tower and a spiral staircase built onto it and vaulted tombs built beneath the floor.

After the Ottomans besieged the Acropolis for two years before its defenders gave in, the Parthenon was converted to a mosque in the 15th century. The tower was extended upward and became a minaret, the Christian altar and icons were removed, and the walls were whitewashed to cover Christian imagery. The basic structure remained intact.

In 1687, during the Great Turkish War of 1583-1699, Venetians attacked the Acropolis. The Ottoman Turks fortified it and stored gunpowder in the Parthenon as well as sheltering local Turks there. A Venetian mortar blew up the gunpowder, demolishing the building’s center and felling the inner sanctuary’s walls and columns on the south, north and east. The columns brought down marble sections above. The catastrophe killed about 300 people and caused fires that burned many homes. The Turks recaptured the Acropolis from the Venetians and used some of the rubble to erect a smaller mosque inside the shell of the ruined Parthenon. Parts of the remaining structure were looted for building material.

This section of the north frieze was badly damanged in the Venetian explosion.

During the 18th century, it became trendy for the sons of wealthy British families to take tours of Europe, especially ancient sites such as the Parthenon. At this point, the Acropolis was in ruins and the Ottomans had converted it into a garrison. Travelers hauled off items that they thought would be destroyed anyway and there was a local black market in them. The Acropolis was used as a quarry, with marble sculptures that fell off the buildings burned to obtain lime for building projects. Irish painter Edward Dodwell wrote that marble from the Parthenon had been repurposed in garrison cabins. Many Europeans visited the ruins and drew and painted them. Some produced and published the first measured drawings of the Parthenon in 1787.

In 1796, the 7th Lord Elgin built a country mansion at Broomhall in Scotland using an architect who shared his passion for ancient Greek art and architecture. When Elgin was appointed British ambassador to the Sublime Porte of Selim III, the Ottoman Sultan of Turkey, in 1798, the sultan ruled Greece. The architect asked Elgin to hire artists to create replicas of the sculptures at the Parthenon so they could be installed at Broomhall.

At the time, the sultan wanted to cultivate close ties with the British to help him defend himself against Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt, which was indirectly under Ottoman rule. When Elgin traveled to Constantinople with his new wife, the sultan lavishly received the two Britons.

Elgin hired artists to take casts and drawings of the Parthenon under the supervision of Neapolitan court painter Giovani Lusieri. Local Ottomans demanded large daily payments to gain access to the Parthenon and refused to let Lusieri set up scaffolding, so Lusieri asked Lord Elgin to intervene with the sultan to get a firman, or edict, giving Lusieri access to the site. Supposedly, Lord Elgin got authorization on July 6, 1801, not just to take casts and measurements of the sculptures but to take pieces of stone that had old inscriptions and figures. The decision to remove the sculptures on the Parthenon was made by Philip Hunt, Elgin’s representative in Athens who persuaded the governor of Athens to interpret the document broadly.

Elgin's published defense written later said: “In the prosecution of this undertaking, the artists had the mortification of witnessing the very willful devastation, to which all the sculpture, and even the architecture, were daily exposed, on the part of the Turks and travelers…. Many of the statues on the posticum of the Temple of Minerva, (Parthenon), which had been thrown down by the [Venetian] explosion, had been absolutely pounded for mortar, because they furnished the whitest marble within reach….”

“Besides, it is well known that the Turks will frequently climb up the ruined walls, and amuse themselves in defacing any sculpture they can reach or in breaking columns, statues, or other remains of antiquity, in the fond expectation of finding within them some hidden treasures.

“Under these circumstances, Lord Elgin felt himself impelled, by a stronger motive than personal gratification, to endeavor to preserve any specimens of sculpture, he could, without injury, rescue from such impending ruin.”

Elgin also was concerned that French artists, who had already hauled off some of the sculptures and placed them in the Louvre museum in Paris, were planning to do the same with more of them.

Elgin acquired some 21 figures from the east and west pediments, 15 or 92 metope panels depicting battles between the Lapiths and Centaurs and 75 meters of the interior Parthenon frieze. He nabbed more than half of what now remains of the Parthenon’s sculptural decoration. He also acquired a Caryatid from the Erechtheum, four slabs from the parapet frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike, and other architectural fragments of Acropolis buildings.

Elgin later said he had obtained the firman from the Sultan, but the only thing he could produce was a document that claimed to be an English translation of an Italian copy of the document, which is now in the British Museum. Its authenticity has been questioned because it didn’t follow the form of a firman. The document was recorded in an appendix of a report by an 1816 parliamentary committee that convened to examine Elgin’s request that Britain buy the marbles. The report said that the document in the appendix was an accurate translation, in English, of an Ottoman firman dated July 1801. The original document has not been located although it was the common practice to preserve firmans issued by the Sultan in the Ottoman archives.

A 1967 study by British historian William St. Clair, Lord Elgin and the Marbles, concluded that the clause allowing the British to take stones with old inscriptions and figures probably did not mean art decorating the temples. Privately, some members of the Elgin party, apparently including Lady Elgin, thought they were authorized to take only objects that they found while excavating. Nonetheless, the columns’ capitals, metopes and frieze slabs were hacked off and some sliced into smaller sections, damaging the building as well.

An English travel writer who watched the removal of the marbles wrote that the Ottoman fortress commander tried to stop the removal of the metopes but was bribed to allow it.

Such firmans along with bribes were not uncommon - Edward Clarke and his assistant obtained authorization from Athens’ governor for the removal of a statue of the goddess Demeter with Lusieri’s intervention. This despite local people rioting against the removal of the statue, which they worshipped. Clarke also removed another marble from Greece which he donated to the University of Cambridge along with Demeter. It is now in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

Supporters of Elgin removing the sculptures say that Elgin had to have gotten a second firman to ship the marbles to Britain. After all, it wasn’t as though he tucked them under his coat and boarded a ship – they occupied more than 200 boxes that were loaded onto wagons and transported to the port of Piraeus to be shipped to England. Elgin apparently was far more concerned that the marbles would fall into French hands than that he would be prevented from taking them out of Greece. It does seem that the Ottoman ruler at the least turned a blind eye to Elgin’s project in exchange for closer British ties.

A ship carrying some of the marbles sank in a storm near southern Greece, and Elgin had to hire divers to salvage them, an operation that took two years. The marbles eventually made it to England, but Elgin himself was nabbed and imprisoned for three years by the French on his way home to England. Once he got there, he negotiated to get the Ottoman government to authorize a second shipment of sculptures which left Pireaus in 1809. The final shipment of 80 boxes was sent in 1812.

Many Britons were enthusiastic about the Parthenon marbles being shipped to Britain, although some thought they lacked the ideal beauty of other sculpture collections. Lord Byron denounced Elgin as a vandal. His poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, published in 1812, said:

Dull is the eye that will not weep to see

Thy walls defaced, thy mouldering shrines removed

By British hands, which it had best behoved

To guard those relics ne'er to be restored.

Curst be the hour when from their isle they roved,

And once again thy hapless bosom gored,

And snatch'd thy shrinking gods to northern climes abhorred!

Sir John Newport called the taking of the marbles "the most flagrant pillages." Even Clarke called the removal of the metopes a "spoliation: and a greater injury than that inflicted on the Parthenon by the Venetians. Sir Frances Ronald wrote that "If Lord Elgin had possessed real taste in lieu of a covetous spirit he would have done just the reverse of what he has, he would have removed the rubbish and left the antiquities."

Elgin wrote the defense of his actions in a pamphlet, Memorandum on the Subject of the Earl of Elgin’s Pursuits in Greece, in 1810. Parliament exonerated him after a debate.

Meanwhile, Elgin’s wife left him, apparently for another man whom she eventually married. Elgin had to sell the marbles, which he was exhibiting in a London house, to pay for the costly divorce settlement.

In 1816, Elgin sold the marbles to the British government for 35,000 pounds, about half of what it cost him to acquire them. The vote was 82 in favor of the sale and 80 against. A parliamentary committee concluded that the monuments should be given "asylum" under a "free government" such as the British one.The sculptures were installed in the Elgin Room in the British Museum along with molds of pieces Elgin hadn’t taken. Large crowds went to see them.

Other than serving as a Scottish representative peer until 1840, Lord Elgin thereafter withdrew from public life. He remarried and had a family with his new wife, including his son James Bruce who became the 8th Earl of Elgin. James as governor of Canada was praised for having negotiated a pivotal treaty that allowed Canada to market its goods in the United States without becoming a part of the United States. However, Bruce is among the most reviled figures in history from China’s point of view because of his role in the 1860 Opium War and burning and looting of the emperor’s summer palace. The ruins of the palace are considered the most prominent symbol of foreign imperial aggression in China. His writings indicate that he was a reluctant British warrior. Of the British bombardment of the southern Chinese trading center of Canton as part of the Opium War, he confessed to his wife that "I never felt so ashamed of myself in my life."

He went on to become viceroy of India and died and was buried there. His legacy survives in the naming after him of Canadian towns, a peninsula and streets and bridges in India, Hong Kong and Singapore. His son, the 9th Earl of Elgin, was viceroy of India during a famine in which between 4.5 million-11 million people died. He headed a commission to investigate the Boer War in 1902-03 which was notable for the British Empire officially considering the views of common soldiers and people affected by military operations.

Elgin said in his pamphlet that he went to Rome to consult with Italian sculptor Antonio Canova, the world’s best sculptural explorer of the time, on how to restore the marbles. “Canova declared, That however greatly it was to be lamented that these statues should have suffered so much from time, and barbarism, yet it was undeniable, that they had never been retouched, that they were the work of the ablest artists the world had ever seen… and had been found worthy of forming the decoration of the most admired edifice ever erected in Greece… it would be sacrilege in him, or any man to presume to touch them with a chisel.”

British artists concurred, “and all idea of restoring the marbles has been deprecated.”

Have the British preserved the marbles well? Over the years, they suffered some damage from London’s notorious 19th-20th century pollution and cleaning by the museum staff. In 1838, scientist Michael Faraday described applying water, fine gritty powder, alkalis both carbonated and caustic and dilute nitric acid in a futile attempt to restore the patinaed marbles to whiteness. Museum official Richard Westmacott in 1858 wrote that some of the marbles had been much damaged by ignorant or careless moulding with oil and lard and restorations in wax and resin, which caused discoloration. In 1937-38, when a new gallery was built to house the collection, Lord Duveen who financed the gallery arranged for the masons to remove discoloration from some of the statues using scrapers, a chisel and carborundum stone. This scraped away detail on many of the carvings by removing as much as a tenth of an inch from them. The museum has acknowledged the mistake but insisted that the main cause for damage was 2,000 years of weathering on the Acropolis and that techniques similar to those used by the British were also used in Greece.

The marbles were placed in storage during the Nazi bombing of London. The gallery suffered extensive damage which was later repaired.

British Museum documents also reveal minor accidents, thefts and vandalism, including two schoolboys knocking off part of a centaur’s leg in 1951, a west pediment figure being chipped by a falling glass skylight in 1961, and vandals scratching lines and letters on figures in 1955 and 1970. A dowel hole in a centaur’s hoof was damaged by thieves trying to extract lead pieces from it.

The Elgin marbles inspired replicas across England and became an important part of the British empire’s 19th century culture. They influenced the way in which great museums display and interpret human culture. They lost meaning from being torn from their original context, but gained new meaning from being seen next to and compared with Assyrian, Egyptian, Roman and other Greek artifacts. An entire intercultural field of studies developed alongside globalization in which the British empire played a dominant part.

Patrons at the British Museum view the Elgin sculptures.

This statue may be Dionysius, who may have originally been holding a cup in his hand.

Greece gained independence from the Ottoman empire in 1832. Searching for a nationalist symbol to unite the war-torn country, the country’s new ruler made the relatively small town of Athens his capital as a symbol of the resurgence of Greece. Greece began to restore the Acropolis and retrieve looted art. The minaret on the Parthenon was demolished along with other medieval and Ottoman buildings on the Acropolis to return the site to its 5th century B.C. state. The Parthenon became the national symbol of Greece.

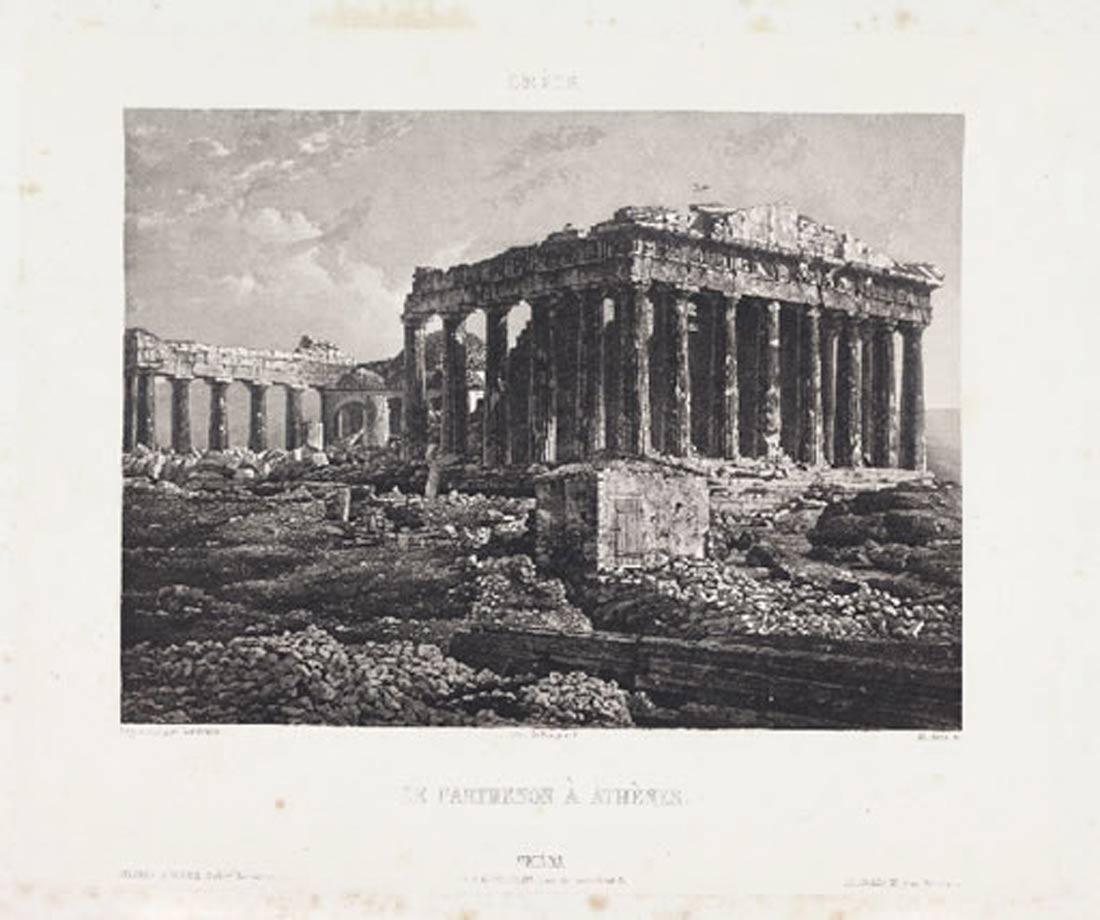

An 1839 photo of the Parthenon shows the state of ruin in the early 19th century. This photo was taken after Elgin stripped parts of the frieze.

Since then, intermittent attempts have been made to get the Elgin marbles back. A campaign to repatriate them to Athens began in the 1980s. The International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures, founded in 2005, unites organizations from almost 20 countries, including Britain, that are trying to get the statues returned to Greece. The Greek government’s goal is for the complete Parthenon frieze to be unified and restored.

UNESCO offered to mediate between Greece and the United Kingdom in 2014 to resolve the dispute, but the British Museum refused to work with it on the grounds that UNESCO works with government bodies, not museum trustees.

A large-scale restoration of the Acropolis began in 1976 and has been on-going since. An archaeological committee documented every artifact on the site and architects used computer models to determine their original locations. To prevent further damage from pollution and acid rain, the original sculptures were removed to the Acropolis Museum, where they are displayed with spaces left should Greece ever persuade Britain to return the marbles. High-quality replicas replaced the removed artwork outside. Britain’s argument that Greece had nowhere to keep the marbles dissolved with the 2009 opening of the Acropolis Museum.

A laser technique was used on the Athens marbles that shows original chisel marks and the veins on horses’ bellies. Some similar details had been scraped and scrubbed off with chisels at the British Museum to try to whiten the marbles there.

The Greek campaign to reunite the sculptures is aimed at allowing visitors to appreciate them in their historical environment as a whole and to permit their fuller understanding and interpretation. The Greeks also state that the marbles may have been obtained illegally and should be returned to their rightful owner.

Sweden, the University of Heidelberg, Germany, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the Vatican have returned fragments to Greece.

Greece has requested only the return of sculptures from the Parthenon, saying it would not set a precedent for other such claims because of the “universal value” of the Parthenon.

The Greeks say the safekeeping of the marbles is ensured at the new museum, which was built to hold the Parthenon sculptures in natural sunlight that characterizes the Athenian climate and arranged in the way the sculptures would have been on the Parthenon. The museum's facilities have state-of-the-art technology for protection and preservation of exhibits. There is a strong case for the view that the sculptures would gain from being seen close to the Parthenon, although they would not be installed on the Parthenon itself.

The Greeks also insist that the friezes are part of a single work of art, and that casts of them could demonstrate the cultural influences that they have had on European art, while the British Museum can’t replicate the context that the marbles belong in.

Directors of the British Museum have not ruled out a "temporary" loan to the new museum, but state that it would be under the condition of Greece acknowledging the British Museum's claims to ownership.

It comes down to how the world's great cultural icons are to be shared. Are the marbles owned by those in the place where they were made or could they legitimately become the possessions of others in the world?

British Museum director Hartwig Fischer, in a January 2019 interview with the Greek daily newspaper Ta Nea, defended the British museum’s incorporation of the Elgin marbles as a “creative act. “

“The imperial patronage of the British Museum has no limits,” George Vardas, secretary of the international association for the reunifications of the Parthenon sculptures, retorted in the Greek paper Vardas. Fisher’s comments, he said, come from “amazing historical revisionism and arrogance.”

“What is the creative cause of the destruction of the temple and the plundering of the keys of the ancient history of a nation?” he asked.

Fischer said that the sculptures “tell different stories” about the Parthenon, which at various times was a temple of Athena, a Christian church, and a mosque. The museum shows the sculptures in a context of world culture, he said.

“Since the beginning of the 19th century, the monument’s history is enriched by the fact that some [parts of it] are in Athens and some are in London where six million people see them every year,” Fischer argued.

He also said the sculptures were no more made for the Acropolis Museum, an archaeological museum in Athens opposite the Parthenon, than they were for the British Museum, neither being their “original context.”

The British government would have to rewrite laws to return the sculptures because their legal owners are the British Museum’s trustees, on whom the responsibility of preserving the museum’s collections for future generations was conferred by the British Parliament. In 2018, British Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn pledged to oversee the scuptures return to Greece if he were prime minister.

In April, the president of Greece, Prokopis Pavlopoulos, said the British Museum was a “murky prison” housing the Elgin Marbles as trophies and that Greece was engaged in a “holy battle” for their return to Greece.

“The Trustees remain convinced that the current locations of the Parthenon sculptures (in London and Athens) allow different and complementary stories to be told about the surviving sculptures, highlighting their significance for world culture and affirming the universal legacy of ancient Greece,” a British Museum spokesman said.

Opponents of restoring the marbles to Greece say that fulfilling all restitution claims would empty most great museums and that Parthenon marbles also are kept by other European museums. They say a legal time limit for Greece to pursue the issue in court has passed. In a 2005 case involving Nazi-looted Old Master artwork that the British Museum wanted to return to the family of the original owner, the English High Court ruled that legislation would be necessary to make such returns because the British Museum Act of 1963 protecting collections for posterity would have to be legally overridden.

The British Museum website has said: "The Acropolis Museum allows the Parthenon sculptures that are in Athens to be appreciated against the backdrop of ancient Greek and Athenian history. This display does not alter the Trustees’ view that the sculptures are part of everyone’s shared heritage and transcend cultural boundaries. The Trustees remain convinced that the current division allows different and complementary stories to be told about the surviving sculptures, highlighting their significance for world culture and affirming the universal legacy of ancient Greece."

School children study the marbles with the help of drawings on their electronic tablets, Britisn Museum.

A number of organizations and celebrities such as George Clooney and Matt Damon have voiced support for the return of the marbles to Greece. BBC TV host Stephen Fry wrote that “it’s time we lost our marbles.” Several polls have suggested that about 40 percent of Britons support the marbles being sent back to Greece while a much smaller percentage oppose it.

The British Museum also has fragments from the Parthenon sculptures from collections unconnected with Lord Elgin.

After the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, some suggested that the United Kingdom be forced to return the marbles to Greece as a precondition for an agreement on Brexit, as an agreement between the European Union and the United Kingdom had to be approved by European Union member Greece.

The 7th Lord Elgin inspired the term “elginism,” the destruction of artworks when they are taken from their cultural and physical context so that scholars can’t retrieve valuable historical information from them and they instead take on the identity of the person who removed them from their setting. UNESCO has put in place international laws to protect monuments from elginism.

Check out these related items

Treasure Room and Two Palaces

In the French palace at Fontainebleau is a treasure room of dazzling artifacts taken by the French army from a palace in Beijing.

The Summer Palace

The Summer Palace, the most famous and heartbreaking of China's glorious imperial gardens, highlights dilemmas in the nation’s past.

Ancient Silk Road Meets High Tech

The International Dunhuang Project digitizes old documents, caves and artifacts to enable global study of Central Asian history.

The Many Layers of Mona Lisa

Mona Lisa has long been mysterious, not just because of her smile. But was mystery or realism her famous creator's object?

What is the Louvre?

The former palace, the world's largest museum, music video and fashion show venue, and global brand has never been more cool.

Marie Antoinette and Barbie

Since she was guillotined in the French Revolution, Marie Antoinette has become one of the most popular icons worldwide.