Election Perspective

COVID-19 testing and ballot photos by Forrest Anderson. Historical photos are in the public domain or available for use under Creative Commons licenses. Photo of Hillary Clinton by Gage Skidmore.

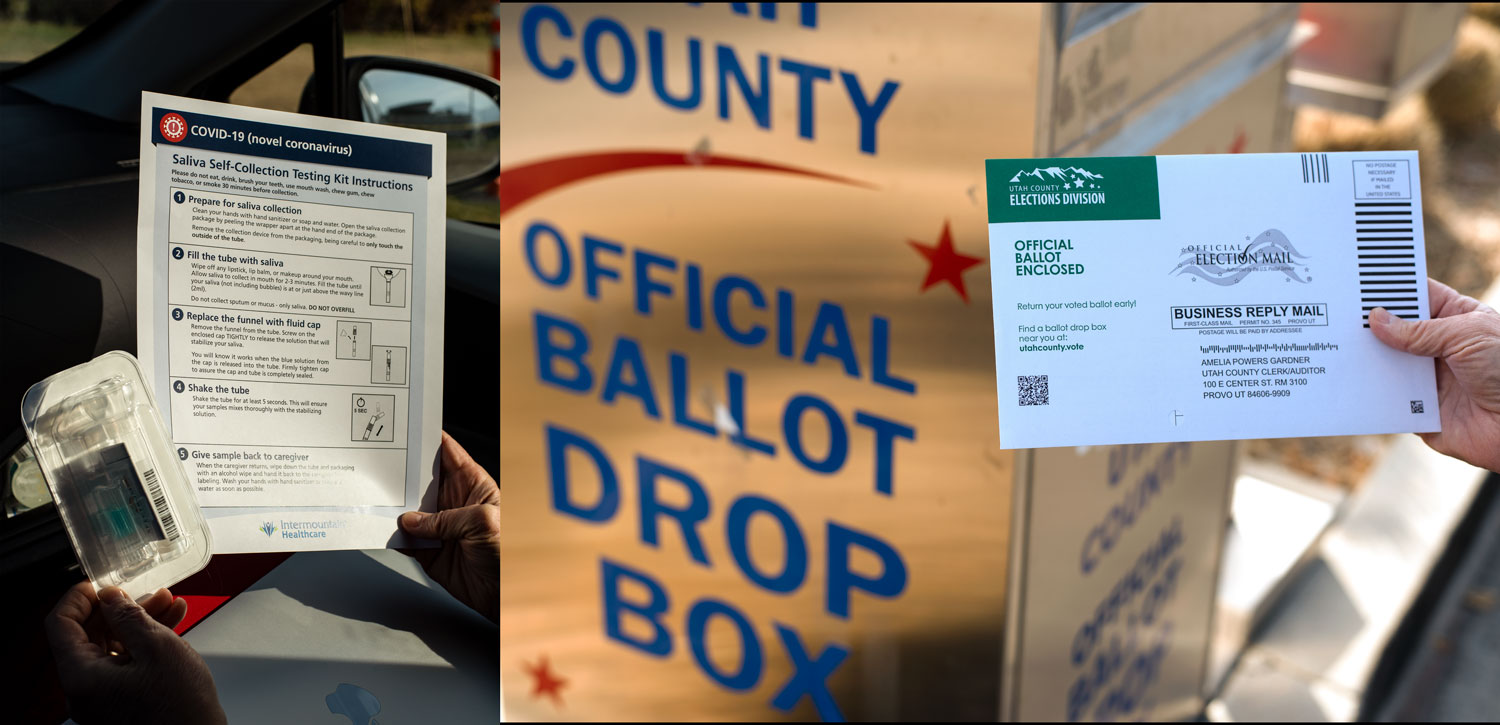

In yet another of 2020’s freakish moments, I both voted and lined up in a long row of cars to get tested for COVID-19 on the same day, having been exposed to a family member/health care worker who has tested positive.

Back at home waiting for the test results (which luckily came in negative), I went looking for some historical perspective about presidential elections. I thought I might be able to find a semblance of sanity by rummaging through the past. Sadly, I was disappointed.

What I found was that the American presidential election process is a lot like a porcelain teacup – fragile but surprisingly durable. Once every four years, our fractious country joins together to place its enormous power in the hands of one leader by each casting an individual vote. Many of those who we have chosen over the years have not been at all up to the job. In some cases, partisan politics and nasty compromises have intervened to throw the election to the oddest of candidates. Small wonder that the citizens of many other countries look on the U.S. election process with wry humor, concern, ridicule or simply a lack of comprehension.

Yet the presidential election process has ensured the continuance of one of the world’s most stable and enduring governments, even as our elections have been followed by bloody wars, made and broken illustrious careers and spawned the nation’s expansion from a few colonies to a large chunk of a continent. Presidential elections have both withdrawn and restored civil rights to people of color over the nation's long history.

It is the very fragility of U.S. elected power that protects the system from the long-term tyranny of a single monarch or dictator. The process's saving grace is the simple collective assumption that if we don’t like the person we elected to govern us, we can return on the wave of a four-year backlash and toss that person out of office for someone new. No one is immune to our collective censure. We assume that our presidents will be imperfect and that we have a right to fire them if they make too many mistakes. It is this factor, not the quality of our leaders or even of our voting decisions, that keeps the United States afloat and delivering a relatively high degree of personal freedom to most of its citizens. While we are roughshod in our handling of those who aspire to govern us, we by and large treat our elective process with considerably more respect. Defeated or retiring presidents are expected to step down without a fuss, defeated candidates to concede with grace. We return to our own business when an election is over. Many of us fume and occasionally hit the streets to protest if we don’t like what current presidents are doing, but mostly we bide our time and wait to cast our next vote.

What follows is my jaunt through a timeline of America's more unusual presidential elections. It doesn't pretend to capture all significant presidential election moments, but it does illustrate the pivotal role that presidential elections have played in shaping our nation. The good news that I learned in my walk through the past is that our vote counts and can have immense consequences. The bad news is that this year's election doesn't have a monopoly on bizarreness, acrimony, corruption or sheer incompetence.

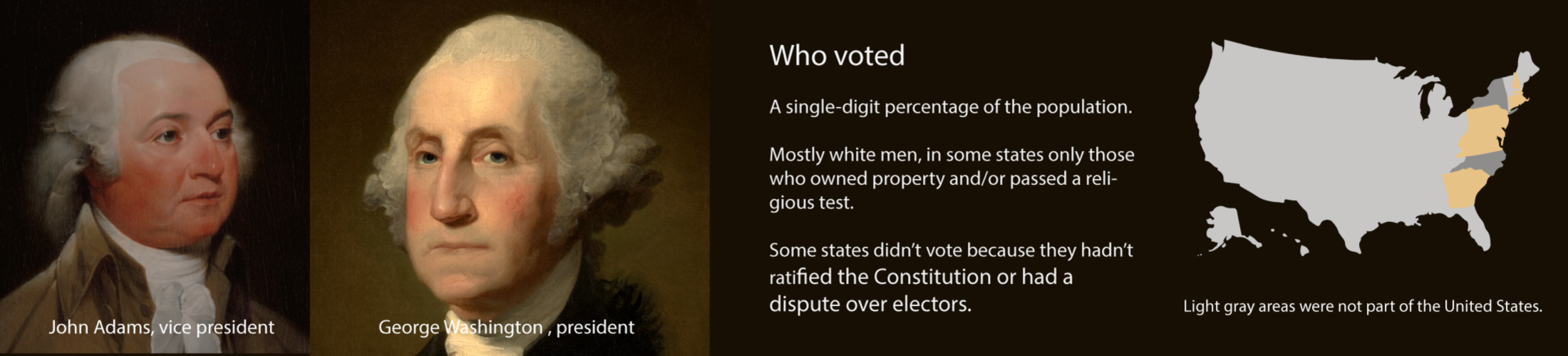

1788-1789

This first presidential election in U.S. history was a shoo-in for George Washington, who didn’t campaign and had no opponent. Sparks flew, however, in the selection of vice president from 11 candidates, which laid the foundation for misinformation in American politics. The Federalists, who supported Adams, spread a rumor that the anti-Federalists had hatched a plot to undermine the United States by electing Richard Henry Lee or Patrick Henry as president instead of Washington. The result was that Adams got the majority of votes and became vice president.

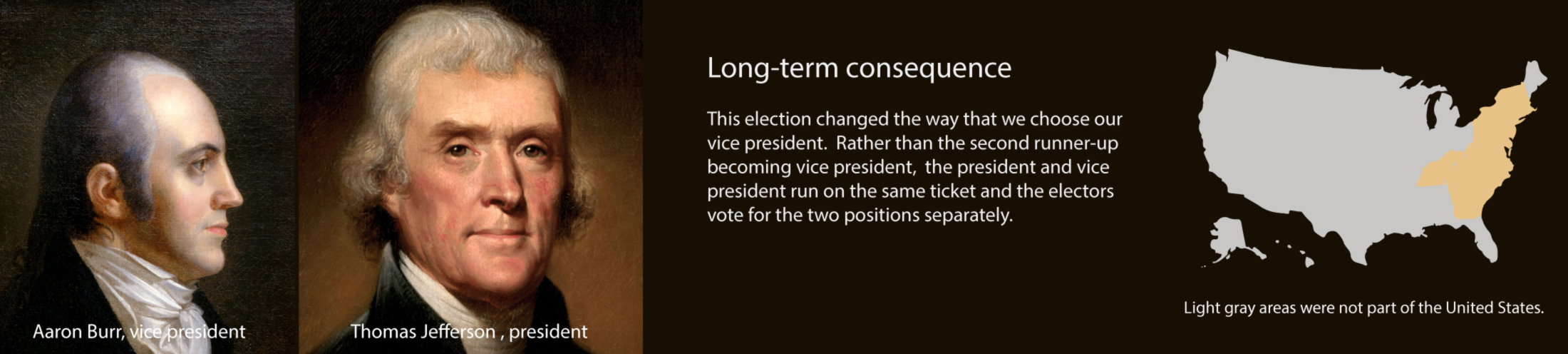

1800

The 1800 election between Thomas Jefferson and John Adams was so bizarre that the outcome resulted in an amendment to the Constitution. In 1800, Thomas Jefferson had been fuming over his loss four years earlier to John Adams. He used resentment against Adams’ tax policies as a way to depict himself as a voice for change. Federalists who supported Adams warned that if Jefferson were elected, "murder, robbery, rape, adultery and incest will be openly taught and practiced, the air will be rent with the cries of the distressed, the soil will be soaked with blood, and the nation black with crimes."

A newspaper spread the unsubstantiated rumor that Adams had planned to marry one of his sons to a daughter of British King George III, launching a new dynastic monarchy, but that George Washington had intervened and threatened to use his sword against Adams.

Underlying the mud-slinging was the tension between two opposing visions for the United States that persists to this day - that of a strong federal government versus decentralization of power to the states.

At the time, the electoral college picked two candidates. The one with the most votes became president, and the second-runner vice president. Jefferson and his ally and vice presidential choice, Aaron Burr, tied for first place, each with 73 votes in what some thought was a Burr conspiracy. Adams got 65 votes and his vice presidential candidate, Charles Pinckney, got 64. The votes lined up geographically, with Adams' supporters sweeping New England, Jefferson's the South, and the Mid-Atlantic states' votes split between them.

The election went to the Federalist-controlled House of Representatives. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton was a Federalist who disliked Jefferson, but he thought Jefferson was a better choice than Burr and he persuaded his allies in Congress to vote for Jefferson on the 36th ballot. Burr became vice president.

The election had a couple of major consequences - one of which stays with us today. In 1804, a 12th amendment was added to the Constitution to specify that electors would vote separately for president and vice president.

The second consequence was that Burr and Hamilton continued to quarrel over politics and Hamilton convinced New York state’s Federalists not to vote for Burr for governor of the state in 1805. Burr lost. He then challenged Hamilton to a duel in which they were to shoot at each other until one of them was dead. Burr shot Hamilton, who died 36 hours later, and Burr was charged with murder in the most famous duel in U.S. history. He was not convicted.

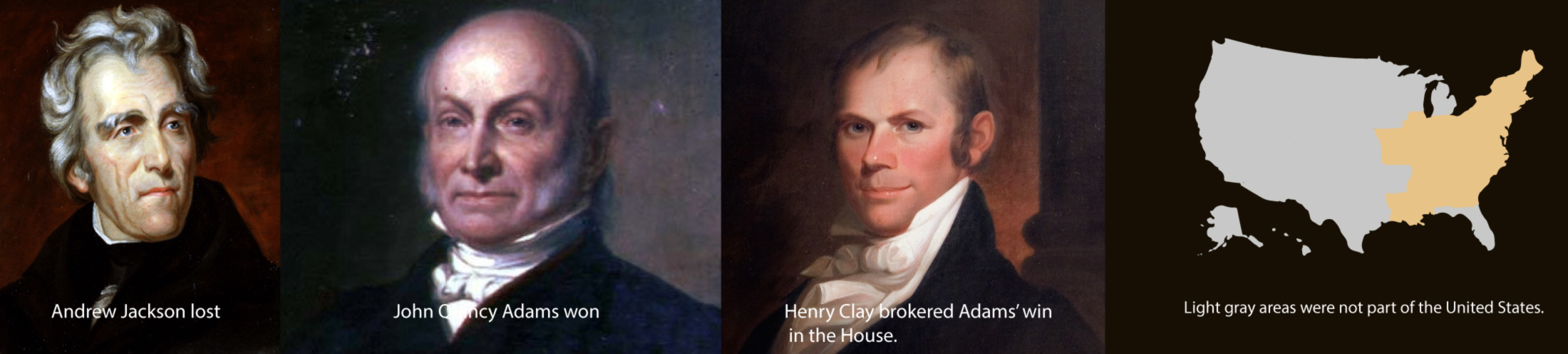

1824

This election took place during the first peacetime economic crisis in the country’s history. Five members of President Monroe’s Cabinet ran for president, making it impossible for any to get the required majority of 131 electoral votes. Andrew Jackson won the popular vote by 41 percent, fewer than 39,000 votes, and captured 99 electoral votes. John Quincy Adams got 31 percent of the popular vote and 84 electoral votes. Lesser numbers went to other candidates.

The election went to the House of Representatives, where House Speaker Henry Clay, who got the least number of electoral votes, was eliminated from contention. However, he still controlled the House and he detested Jackson, who he thought had shed too much blood as a general in the War of 1812. Clay's supporters mostly supported Adams, so Adams won in spite of the popular and electoral college votes. Clay was rewarded with the position of secretary of state soon after Adams’ inauguration, which Jackson famously called a “corrupt bargain.”

1828

Andrew Jackson returned to win the presidency as the head of a new Democratic Party in 1828 by almost 13% in the popular vote. This was partly a backlash against the backroom deals of 1824, and thereafter the nominating of candidates became more democratic with the replacement of caucuses with conventions. There was vicious mudslinging by both sides, including claims that Jackson’s wife was a bigamist, and Jackson accused his wife’s critics of murdering her when she died after he won the election. It was in this election that the Democratic Party started using the donkey as its symbol, after Jackson co-opted it from his opponents who had used it as a slur against him and started putting it on his campaign posters. The elephant as a symbol for the Republicans was later popularized by political cartoonist Thomas Nast.

Jackson’s inauguration party, which was open to the public, was described as a mob scene at which women fainted and men got bloody noses.

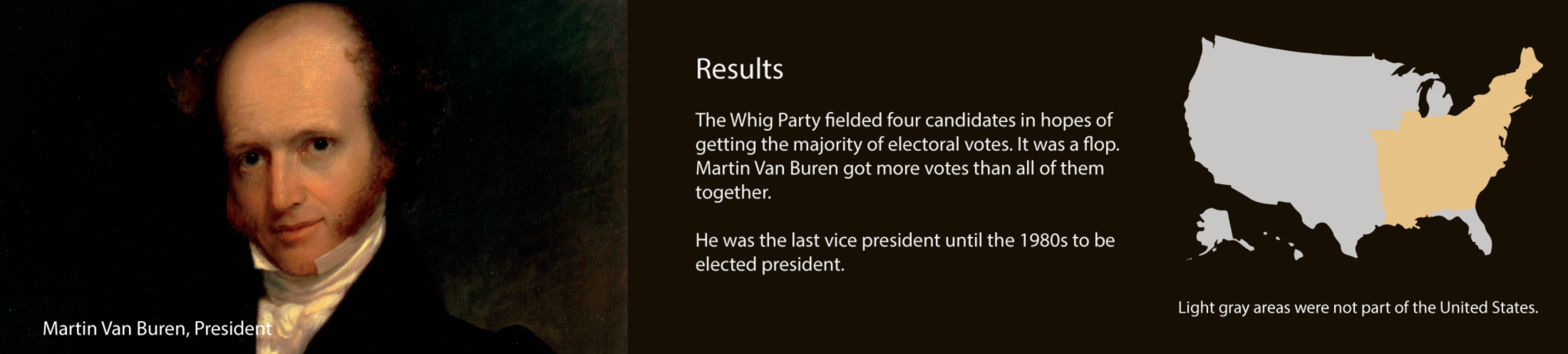

1836

The Whig party ran four consecutive campaigns with four different nominees, in hopes of getting enough electoral votes to send the election to the House of Representatives where they thought they could get enough votes. The Whig candidates got 738,000 votes together but Martin Van Buren received 762,678 popular votes and 170 electoral votes and became president.

1844

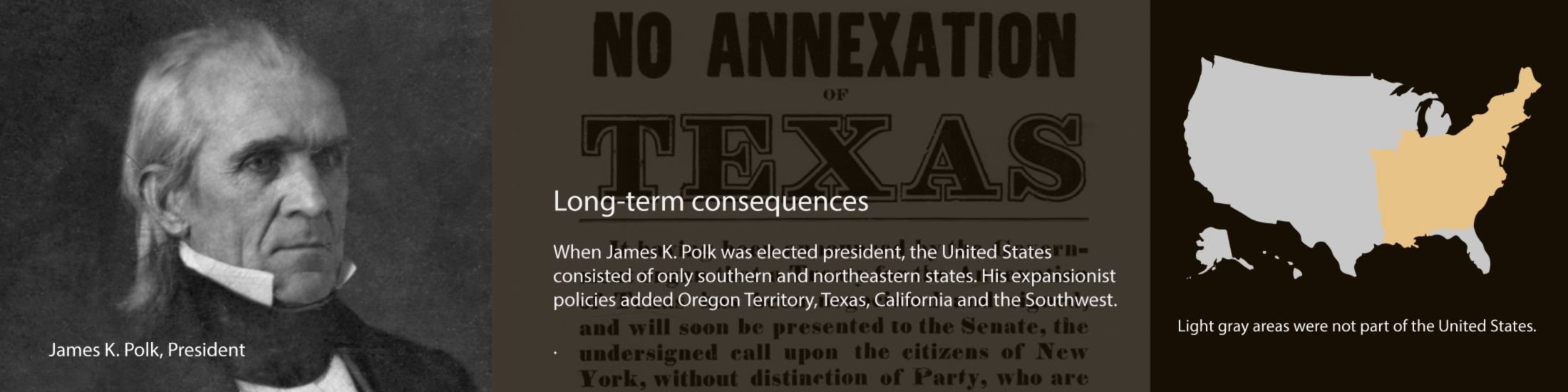

The 1844 Democratic nominee for president was expected to be Martin Van Buren, but the newly-formed Republic of Texas was asking to join the United States. Van Buren’s opposition to this annexation during the Democratic nominating convention resulted in the Democrats choosing James Polk instead. He was such an obscure choice that people went around asking, “Who is James K. Polk?”

“The Democrats must be Polking fun at us!” one Whig paper joked.

Some supporters of his opponent, Henry Clay, were so sure that Clay would win that they ordered Clay some rosewood furniture for the White House bedroom. However, Polk won by just 38,000 votes after campaigning on support for the annexation of Texas and claiming Clay had a weakness for whiskey and gambling. Polk's expansionist agenda resulted in a compromise with Britain over Oregon Territory and the Mexican-American War, which ultimately resulted in the addition of Oregon, California and the Southwest to the United States.

Just after this election in 1845, Election Day was designated nationally as a Tuesday after the first Monday in November. The rationale was that farmers needed a day to get to the county seat to cast ballots, but should not have to travel on Sunday.

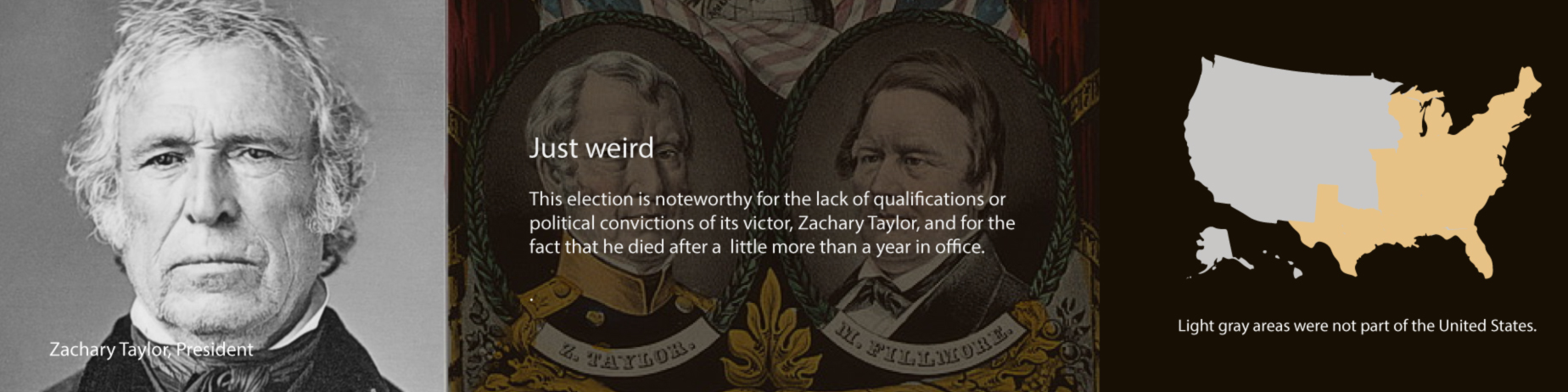

1848

Zachary Taylor had the distinction of never having voted in an election when he became a candidate. Taylor had great name recognition as “Old Rough and Ready” for his role as a general in the Mexican-American War, but he was poorly educated and had no strong stance on the issues of the day. The Whig Party accordingly ran him with no platform, positioning him as a political outsider "without regard to creeds or principles." His opponent, William Cass, was an experienced politician, but he angered abolitionists with his stance that frontier territories should vote on whether to abolish slavery within their borders. The vote was split when former President Martin Van Buren ran on a third-party anti-slavery ticket. He pulled in enough votes to tip the election in Taylor’s favor. Taylor's presidency had little impact, as he died after a little over a year in office and Vice President Millard Fillmore took over.

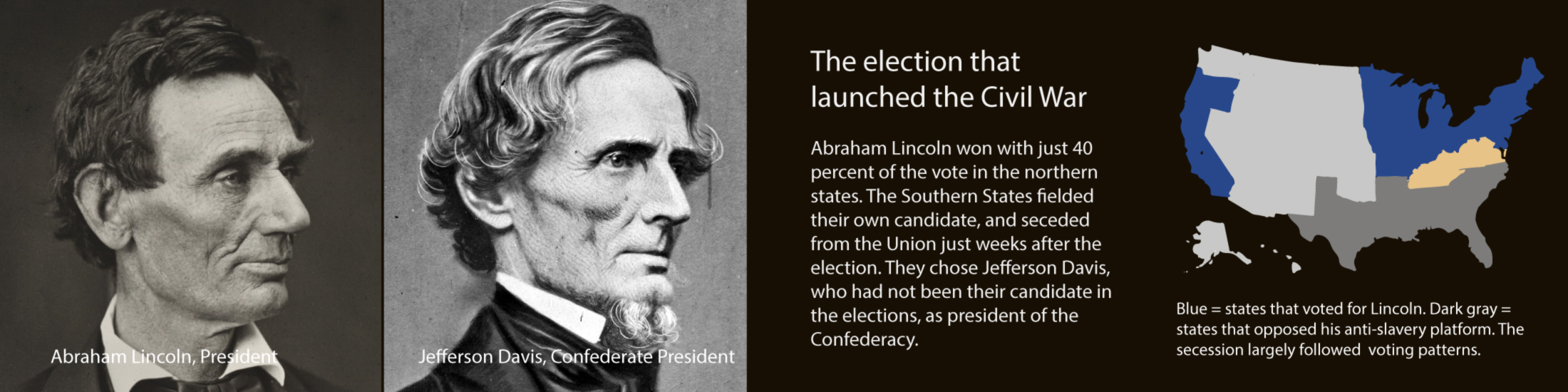

1860

This election had the most violent outcome of any in U.S. history, as it launched the Civil War. Incumbent President James Buchanan urged the Supreme Court to vote pro-slavery in the Dred Scott v. Sanford case. This made him so unpopular that he bowed out of the race to avoid getting assassinated. This opened the way for Republican Abraham Lincoln, a slavery opponent, to go up against Senator Stephen Douglas. Many who had been associated with the Democrats or Whig parties but opposed slavery joined the Republicans, while pro-slavery advocates left their parties and joined the Democrats. The southern branch of the Democratic Party defected and chose Vice President John Breckenridge as their candidate.

Lincoln wasn’t on the ballot in most southern states, and got just 40 percent of the popular vote but won most Northern electoral votes. Breckenridge won most of the southern electoral votes, plus Maryland and Delaware. South Carolina seceded from the Union just six weeks after the election, and six other southern states followed. They formed the Confederacy in February 1861, with Jefferson Davis as president, and the war was on.

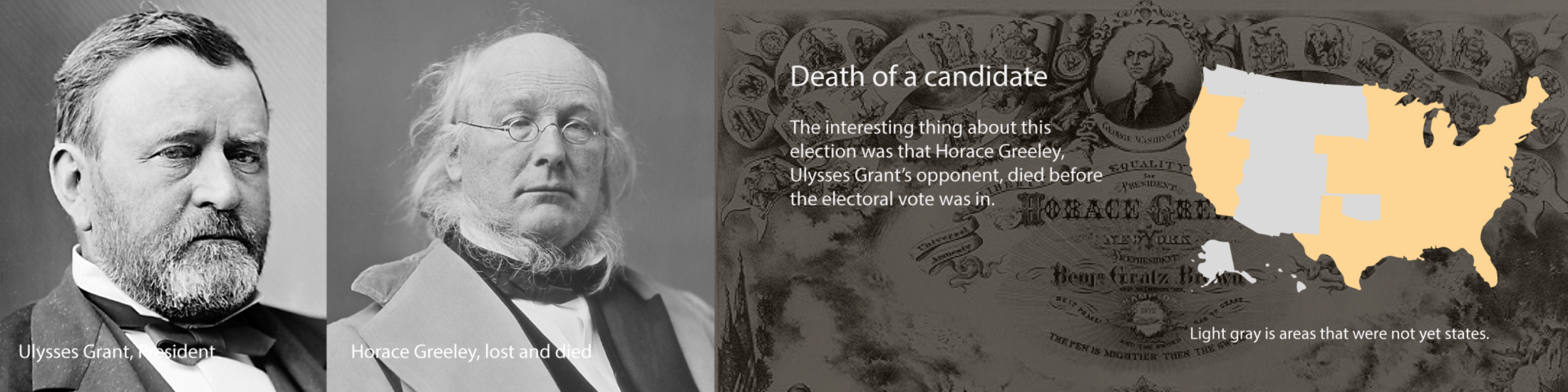

1872

Incumbent President Ulysses S. Grant easily won a second term in this election. He got 286 electoral votes compared with his opponent Horace Greeley’s 66. Before the electoral college votes were in, Greeley died, the only final presidential candidate in U.S. history to die before the election was finished. The first woman to run for president did so this year – Victoria Woodhall, leader of the Suffragette movement.

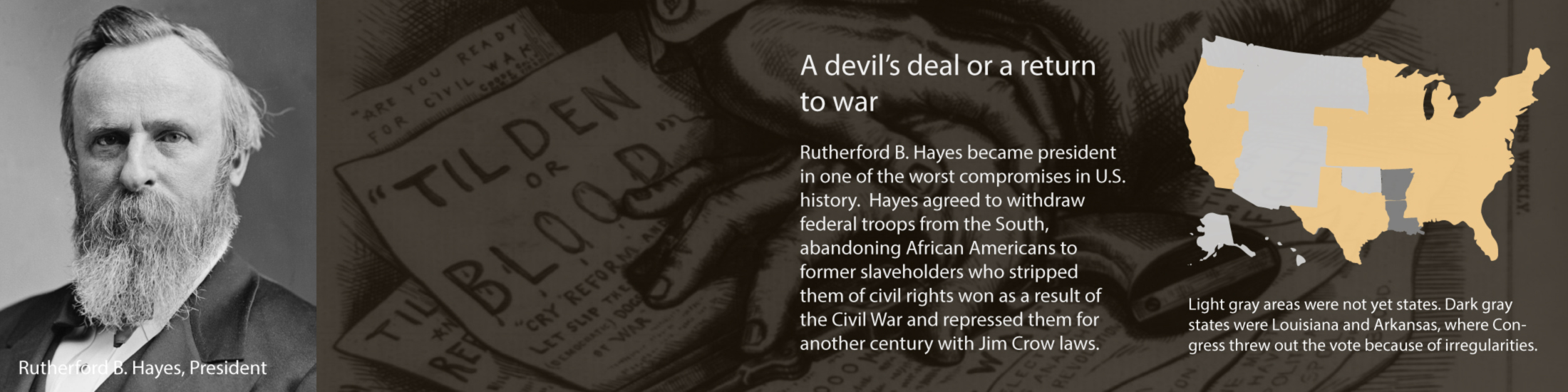

1876

Rutherford B. Hayes, a Republican, and Samuel Tilden, a pro-slavery Democrat, vied in one of the ugliest elections in American history. Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated and federal troops had been stationed across the South in the wake of the Civil War. Roving gangs of white supremacists suppressed votes in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, often in bloody encounters, leading to Tilden winning the popular vote by 250,000 votes and 19 electoral votes. However, he was one short of the required majority of 185. Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina were too close to call, as each side accused each other of fraud. In Oregon, an elector was declared illegal and replaced with controversy. The dispute was so bitter that there was talk of another civil war.

The Senate and House of Representatives deadlocked on the election, and agreed to establish a 15-member electoral commission of senators, congressmen and Supreme Court justices to decide the issue. It included seven Republicans, seven Democrats and one independent. Hayes got the swing vote and all 20 electoral votes from the disputed states, giving him 185 electoral votes. The Democrats threatened to filibuster and block the official vote count. Hayes and Tilden reached a compromise. Hayes would receive 20 electoral votes that he needed to become president if he withdrew federal troops from the South. This effectively abandoned African American citizens to white supremacists who passed repressive Jim Crow laws ending many African American rights that had been won during Reconstruction. These rights were not restored until the 1960s. Some northern Democrats referred to Hayes as “his Fraudulency.”

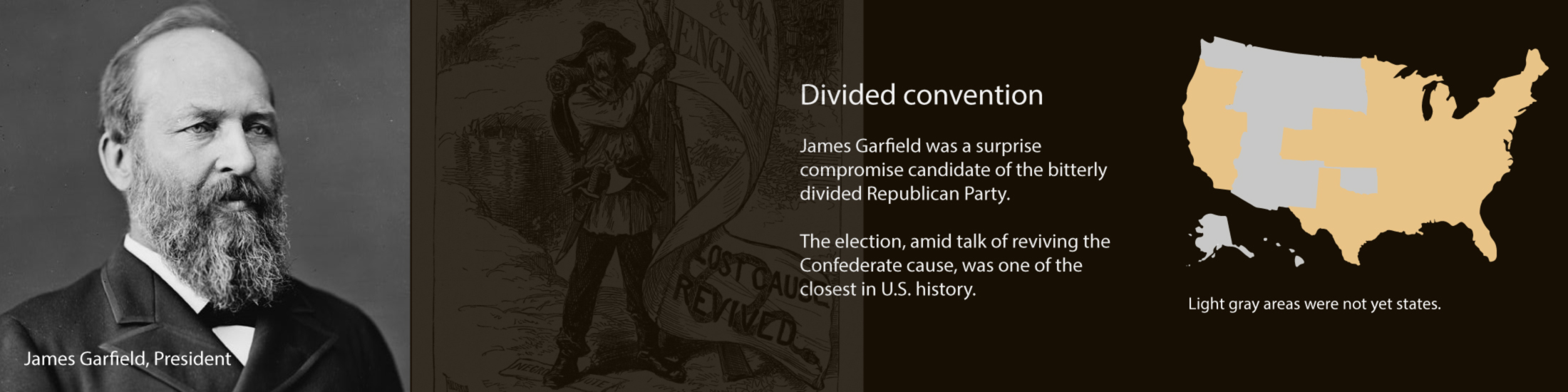

1880

Ohio Congressman James A. Garfield was a surprise consensus candidate after the divided Republican Party held a seven-day marathon convention at which no candidate got the required majority of votes. Garfield, who had attended the convention as another candidate’s campaign manager, emerged on top after 36 ballots. He protested, but ended up running against a former Civil War general named Winfield Scott Hancock. Garfield won by fewer than 10,000 votes, but was killed by an assassin just four months after his inauguration.

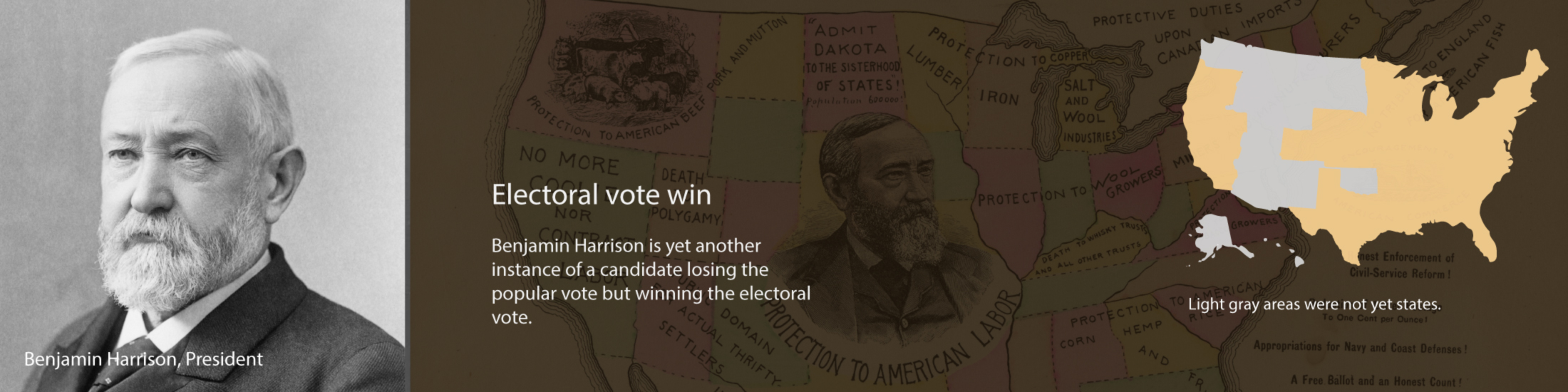

1888

Benjamin Harrison lost the popular vote in the 1888 election against incumbent Grover Cleveland by about 90,000, but won the electoral college. Cleveland returned to the White House in 1893 as the 24th president.

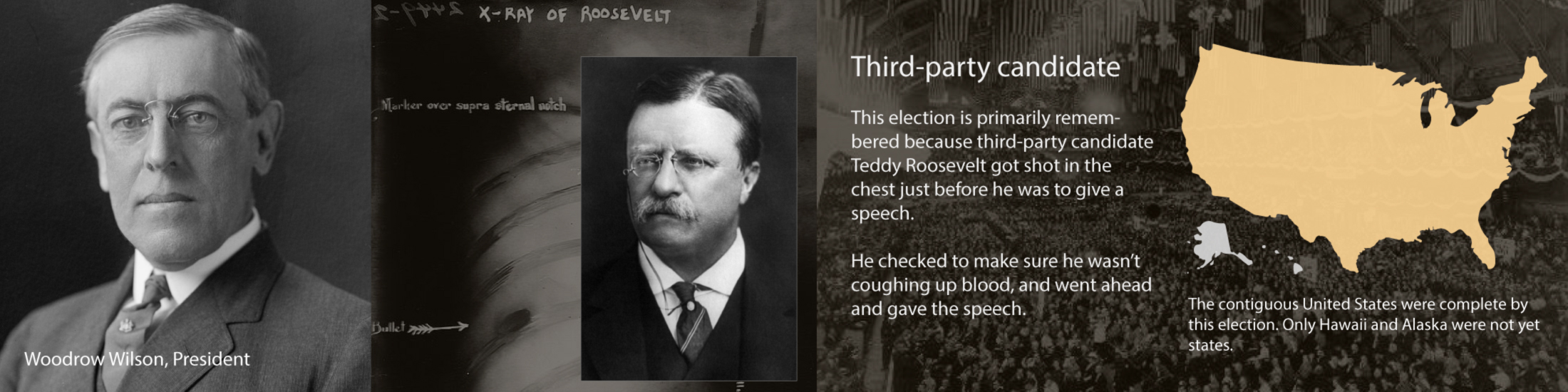

1912

Theodore Roosevelt challenged William Howard Taft in the 1912 Republican primaries and lost, whereupon Roosevelt and his supporters left the Republican Party and formed the Progressive Party. Speaking at a campaign stop in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Roosevelt began his speech by saying, “Friends, I shall ask you to be as quiet as possible. I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot.”

His horrified audience watched as he unbuttoned his vest to show them his bloodstained shirt. He took a bullet-torn 50-page speech from his coat pocket and said, “Fortunately I had my manuscript, so you see I was going to make a long speech, and there is a bullet – there is where the bullet went through – and it probably saved me from it going into my heart. The bullet is in me now, so that I cannot make a very long speech, but I will try my best. “

Roosevelt spoke for the next hour and a half, glaring at his aides whenever they tried to stop him from speaking.

The shooting had occurred not in the auditorium but as he had stood up in an open-air automobile waving his hat to the crowd. Roosevelt’s stenographer put the would-be assassin, who was just five feet away, in a half nelson and grabbed his wrist to keep him from firing a second shot with a Colt revolver.

The crowd around the car beat on the shooter and shouted “Kill him!’ while Roosevelt watched coolly.

“Don’t hurt him. Bring him here. I want to see him,” he said.

“What did you do it for?” He asked the shooter. When the man didn’t reply, Roosevelt said, “Oh, what’s the use? Turn him over to the police.”

Roosevelt then reached inside his overcoat and felt the dime-sized bullet hole on the right side of his chest. “He pinked me,” he said. Coughing into his hand and not seeing any blood, he decided the bullet hadn’t penetrated his lungs and proceeded to the speech venue.

After the speech, Roosevelt had X-rays taken that showed that the bullet had lodged against his fourth right rib on a path up to his heart. His overcoat, eyeglass case and speech had slowed the bullet. Roosevelt telegraphed his wife that he was “in excellent shape” and the wound was trivial.

Roosevelt told his speech audience that vicious election rhetoric had contributed to the shooting. “It is a very natural thing that weak and vicious minds should be inflamed to acts of violence by the kind of awful menacity and abuse that have been heaped upon me for the last three months by the papers.”

It wasn’t Roosevelt’s first encounter with assassination – he had become president in 1901 after an assassin had felled President William McKinley, and subsequently had served for two terms.

Roosevelt and Taft split the Republican vote in 1912, throwing the election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson although he had less than a 50 percent majority in many states. Roosevelt came in second. It was the last time that a major party candidate failed to finish either first or second in a presidential election.

1920

This election was significant not because of the candidates, but because of the voters. It was the first year that women were allowed to vote in presidential elections. Women's vote increased the vote numbers dramatically from 18.5 million in the previous election to 25.8 million in 1920.

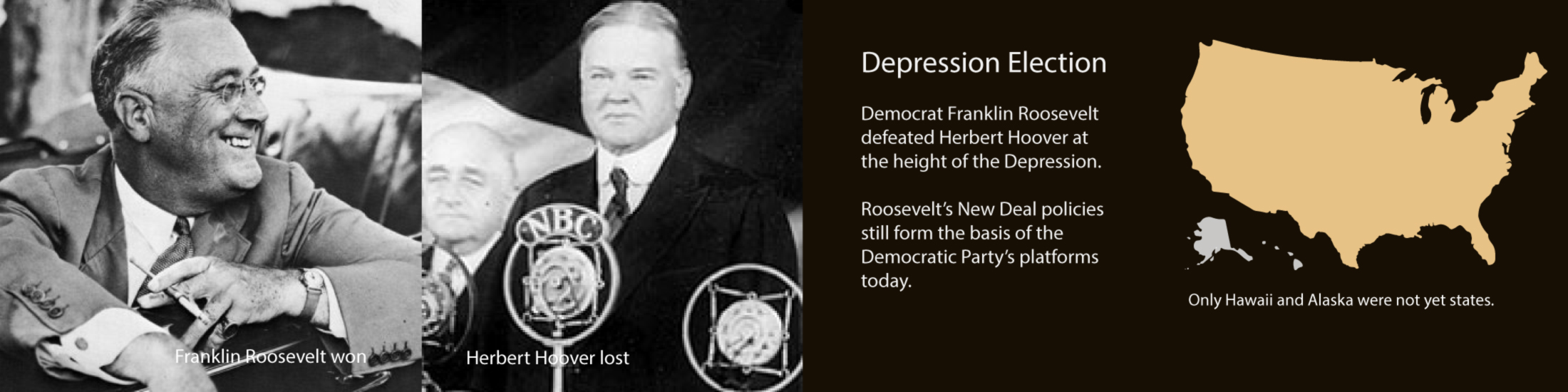

1932

Democrat Franklin Roosevelt came to power during the Depression by forming a New Deal coalition that united urbanites, northern African Americans, southern whites and Jewish voters. This coalition formed the Democratic Party's enduring base.

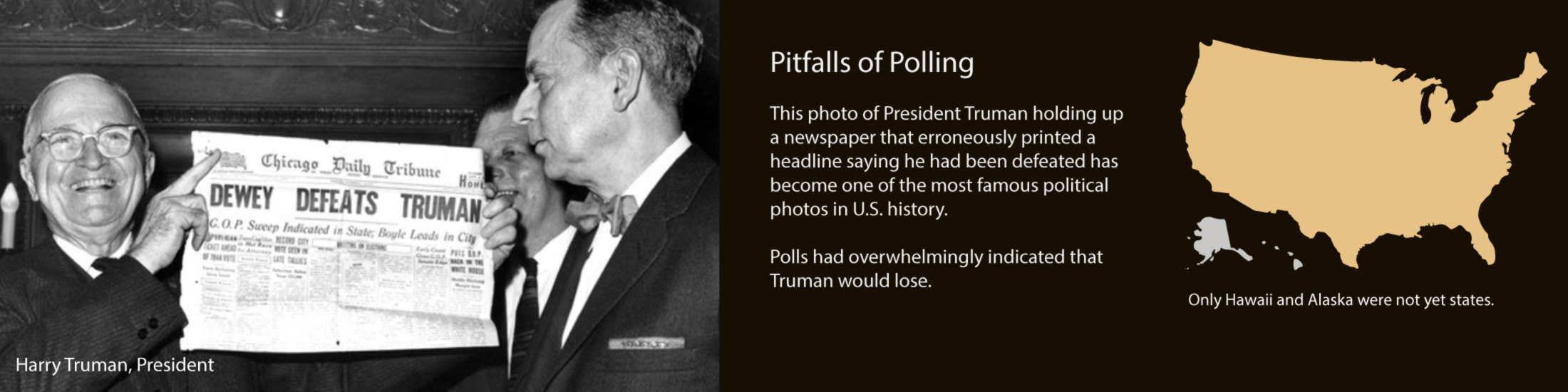

1948

Democratic President Harry Truman trailed New York Governor Thomas Dewey by a significant margin in almost every poll in the months before the 1948 election. Truman’s approval ratings were below 40 percent, while the Republicans appeared to be on the rise because they had gotten a majority in Congress in 1946. The New York Times announced that Dewey’s election was “a foregone conclusion,” Truman's own commerce secretary quit to run against him on the Progressive Party ticket, and the first lady privately acknowledged that her husband was likely to lose. Truman’s public support of civil rights for African Americans lost him the support of southern conservative Democrats who walked out of the Democratic national convention and formed their own state’s rights party known as Dixiecrats behind South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond. Truman campaigned on the platform that Republicans would repeal the popular New Deal programs that had helped bring the country out of the Depression. Truman took a 22,000-mile whistle-stop train tour and courted labor and African American support. He went to bed on election night thinking he had lost, but was awakened by his Secret Service agents at 4 a.m. with the news that he had won by 303 electoral votes to 189. The Chicago Daily Tribune’s famous headline, printed before all of the results were in, read “Dewey Defeats Truman.” Truman posed for a photo-op holding it up, one of the most famous in U.S. political history.

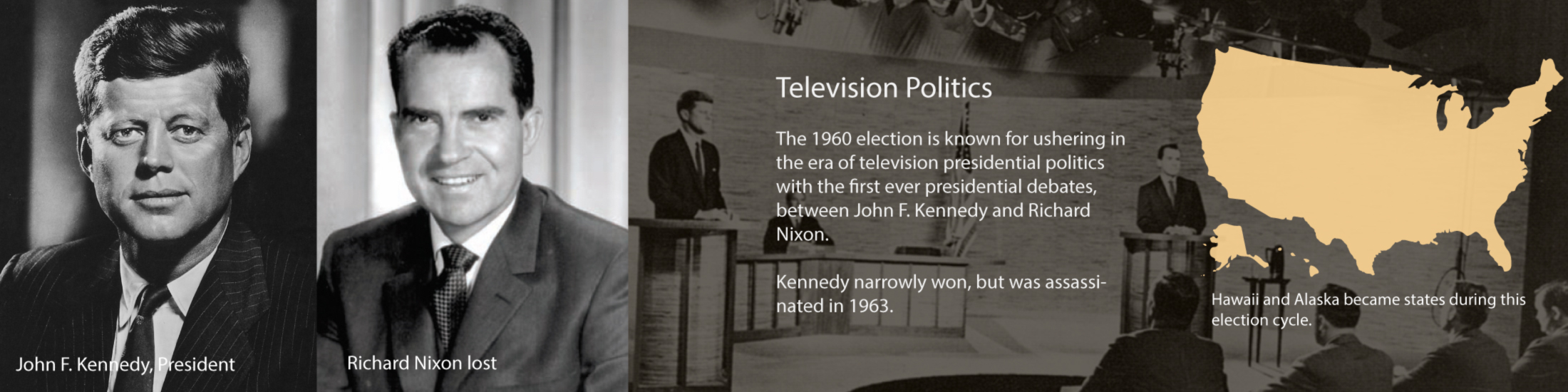

1960

The election in which Democrat John F. Kennedy defeated Republican Richard M. Nixon was noteworthy for a number of reasons. Kennedy was just 43 years old when he became the youngest president ever. He also was the nation’s first Catholic president. The two candidates sparred in four televised debates – the first ever. Kennedy’s performance and tanned, athletic appearance in the first debate was widely credited with giving him the victory, while Nixon, who had a 102-degree fever and a hurt knee, came across as haggard. Nixon fared better in the other three debates, but still lost the election and television became an important part of presidential campaigns.

Some accounts claimed that Chicago mobsters played a role in Kennedy’s victory in Illinois. The election was so close that Nixon could have disputed the vote, but said he didn't want to cause a "constitutional crisis."

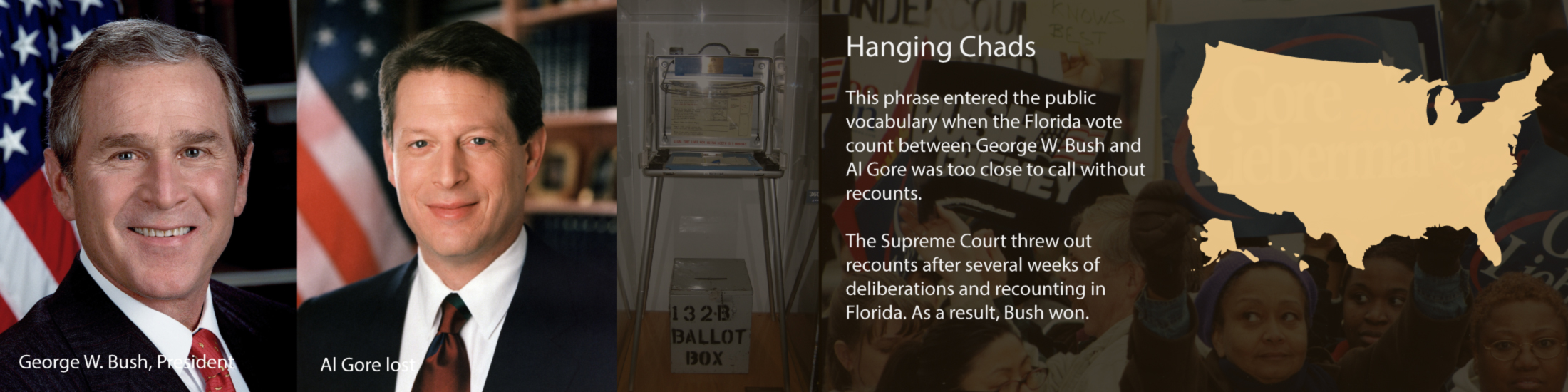

2000

This was the election that just kept on going. Republican George W. Bush was the first candidate in 112 years to win the presidency without winning the popular vote. He was behind Democrat Al Gore by more than 500,000 votes, but it was the electoral vote that was in question in the states of Florida, New Mexico and Florida where the popular vote was very close.

There were just a few hundred votes separating Bush and Al Gore in Florida. Following a mandatory recount in Florida that shrank the margin between the candidates to 327 votes for Bush, the Florida Supreme Court ruled for manual recounts throughout the state. The phrase “hanging chads” became famous because those doing the hand counts had to determine whether partly-attached scraps of paper called “hanging chads” on punch-card ballots should count as votes.

There were heated disputes over confusing and improperly punched ballots, missing names on voter rolls and minority voters getting multiple requests for identification. Bush’s legal team appealed to the Supreme Court for the recounts to stop. It took five weeks before the Supreme Court decided the outcome of the election, ruling 7-2 that a statewide recount by Florida was unconstitutional and that smaller recounts could not go forward. The decision meant that Bush became the next president by a .0009 percent margin.

One of many lasting effects of this election is greater scrutiny of the election process.

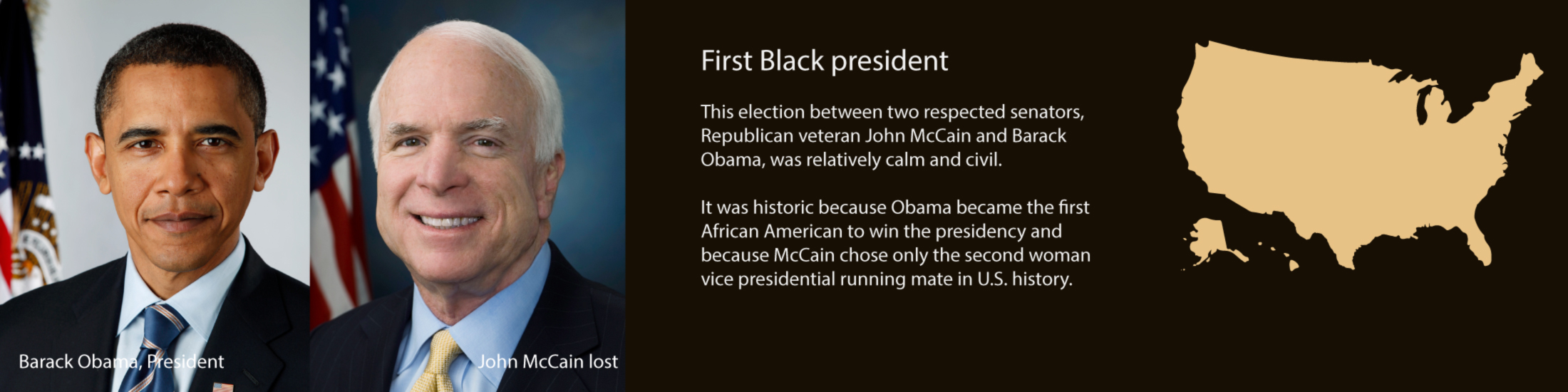

2008

Barack Obama became the first African American to win the White House, triumphing during one of the worst recessions in the country’s history. Obama, a two-year senator, not only defeated the popular Republican senator and war hero John McCain in the final election, but New York Senator and former first lady Hillary Clinton in the Democratic primaries. Obama’s campaign slogan, “Yes We Can,” became an oft-cited American motto.

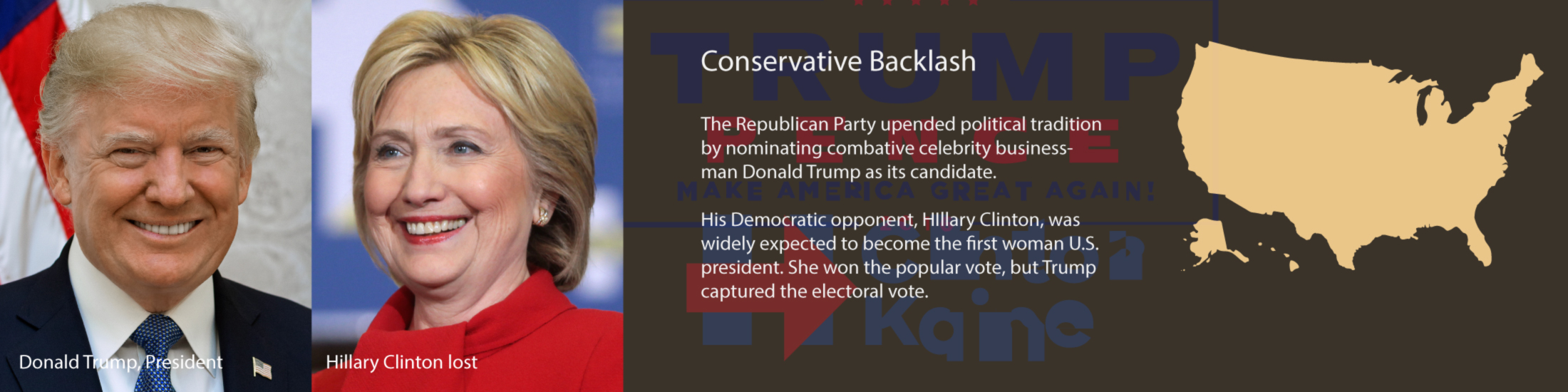

2016

Donald Trump’s election was momentous for a number of reasons – he became president despite losing the popular vote thanks to the electoral college count. He defeated the first woman to win a major party nomination for president. He was a political outlier whose outlandish personal conduct and comments seemed impervious to political backlash. He was the first president in U.S. history never to have held a government position before. At 70, he also was the oldest first-term president in U.S. history. He was the second divorced man to be elected president, after Ronald Reagan.

The primary season was raucous, with 17 Republican candidates who were the largest presidential primary field in U.S. history. Trump dominated headlines with bizarre comments about his opponents amid allegations against him of past sexual misconduct. Democrat Hillary Clinton was challenged by Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders. She won the popular vote by 65,844,6010 to Trump’s 62,979, 636, but Trump got 304 electoral college votes to Clinton’s 227.

The election was upset partially as a result of FBI Director James Comey informing Congress that the FBI was investigating Clinton’s use of her personal email server when she had been secretary of state and that new evidence in this case had been found on the computer of the husband of a Clinton aide during an investigation into whether he had been sexting an underage girl. Two days before the election, the FBI cleared Clinton. The election was notorious for going in the opposite direction of pre-election polls, which had shown Clinton leading, and for allegations of Russian interference in the election.

2020

So here we are. It's obviously too early to draw conclusions about the election's outcome. We do know it will be remembered most for the COVID-19 pandemic which has been the leading campaign issue and has made the election heavily reliant on mail-in ballots.

Check out these related items

Patriotic New York City

New York City, America's great atypical metropolis, taught me what America means. Here are my favorite patriotic sites in the city.

The Racism of Confederate Statues

The racist past associated with the Confederacy and Confederate monuments has a complex history.

Getting A Vaccine against Racism

A mother of non-white children compares her fears for her children because of COVID-19 and her fears for them because of racism.