Heavenly Stone Masons

Photos by Forrest Anderson

In ninth-century France, Christianity was under attack. No one would have thought that it would survive the pagan Northmen who sailed up France’s broad, navigable rivers in Viking ships to loot and burn Christian churches along their route. Weakened by internecine wars, France was defenseless.

Monks cowered in monasteries praying that God would deliver them.

“And so among us the sword of barbarian men rages, unsheathed from the scabbard of the Lord,” wrote one Frenchman. Churchmen and kings desperately bribed the ruthless invaders to withdraw, but they always came back later for more loot.

In 845, the Vikings captured Paris on the eve of Easter, plundered monasteries and churches, and slaughtered priests and monks. They returned 12 years later and burned all of Paris’s churches except three which were spared because the Parisians paid enormous bribes. Notre Dame Cathedral was badly damaged, but Paris strengthened its walls and restored it.

In the 1880s, the city held out through a four-year Viking siege that ended when the French monarchy granted the Northmen land to the north that they already held. Whereupon the Northmen became a French vassal, accepted Christianity, and abandoned their Old Norse language for French. The Northmen then turned their energies toward trade and religion, contributing generously to the Catholic Church and the building of monasteries and churches.

The monasteries built magnificent monastery chapels, and churches that had been destroyed or damaged were rebuilt. Bishops in the cities launched cathedral building and reconstruction projects, sparking a church building boom that became a blend of remarkable engineering and artistic creativity.

Highly skilled master builders went from church site to church site, taking with them their favorite skilled masons and carpenters. Through the eleventh and twelfth centuries, they built Romanesque buildings with two towers on the west, sculpture around the doors, and stone vaulted ceilings. These masons developed transverse arches in the buildings to enable them to move scaffolding after each section of vaulting had been built. The masons learned to make barrel vaults that intersected at right angles and strengthen them with ribs where they met – a step toward the Gothic vault.

The Romanesque underground vault of Saint Denis in Paris. Saint Denis was the first Gothic church, and its architecture illustrates the transition from Romanesque to Gothic style.

With peace, the economy prospered, the political structure became stronger, the population and towns grew, and wealth and power concentrated around royal dynasties in France, England, Germany, and Italy.

At the same time, the Normans conquered Sicily, bringing Arab and Byzantine influences of southern Italian architecture to France, sometimes because skilled Greek and Arab workers were imported. The crusades expanded this cultural exchange.

Since the Roman Empire, there had been a French tradition of wealthy segments of society such as shipbuilders contributing to the building of religious edifices to a goddess called the Great Mother. This tradition was carried forward into the medieval era in cult of the worship of the Virgin Mary which inspired the building of churches in her honor.

In the optimism of the times, dark Romanesque churches seemed out of place. Worshippers wanted light-filled spaces. This impulse eventually was set in stone in Gothic architecture.

The first great Gothic church was Saint Denis in Paris, a rebuilding of an old abbey church outside Paris that housed what was believed to be a nail from Christ’s True Cross, other religious relics, and the remains of many French kings.

Saint Denis is a masterpiece of stone and stained glass.

The church’s abbot, Abbot Suger, had Saint Denis rebuilt in a soaring light-filled style to highlight gold, gems, and marble that his prosperous abbey acquired. Suger was the epitome of the Gothic craftsmen of the time. He personally chose the building’s stone and went to the forest to choose the trees for roof timbers. A cult of miracles emerged around his meticulousness in finding the right stone, the right forest with the right number of trees, and a cache of gems from a collection sold by King Henry I of England. The jewels ended up on a large colorful crucifix in the church.

Stories of other miracles circulated, such as a visiting bishop saving the unfinished, swaying church during a violent storm by holding out a sacred relic, the arm of St. Simeon.

Suger brought skilled masons, sculptors, glassmakers, and other artisans from Normandy and southern France or had them trained on the site of Saint Denis. The church had pointed arches, a cross-ribbed vault, and stained-glass windows that filled the building with dazzling colored light. The stunning windows depicted sacred scenes from the Bible that involved light.

The king, queen, nobles, and clergymen in elaborate clothes attended the 1144 consecration of the building amid the glitter of golden vessels. It was an event to remember, and awed clergymen who were present went home and sparked a wave of church building throughout France.

Gothic architecture was elevated to a high art as masons and carpenters developed their skills and created ever more soaring, light-filled buildings.

Notre Dame de Paris was rebuilt with a facade of sculptures depicting the Virgin Mary, the Christ Child, kings and bishops, and a statue of Maurice Barbador who supervised much of the building’s construction.

Notre Dame de Paris.

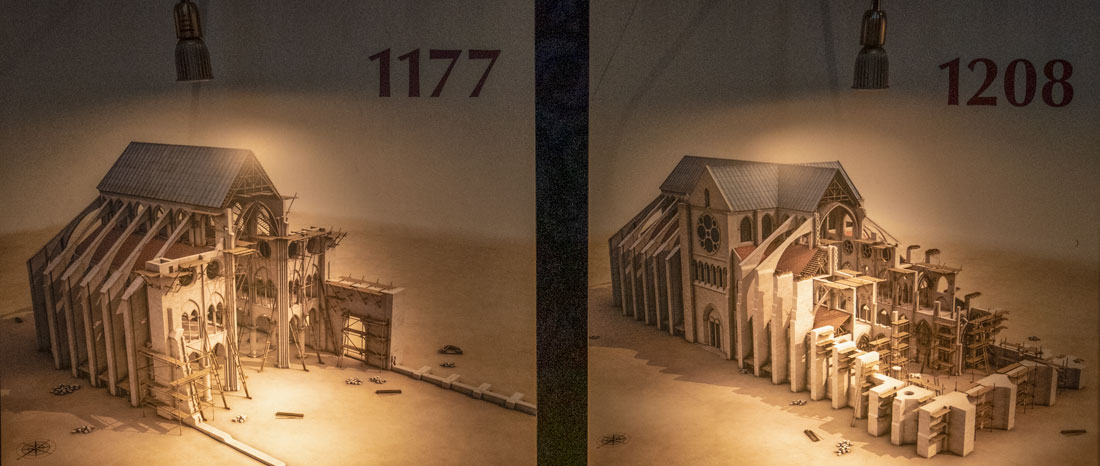

Notre Dame took 200 years to build. Here are two drawings of stages in its construction, from a display in the church.

A corps of skilled workmen assembled along with the building boom, organized into guilds with wages negotiated between guild masters and cathedral chapters or set by law. Teams of these workers went from city to city as cathedrals reached building phases in which their skills were needed.

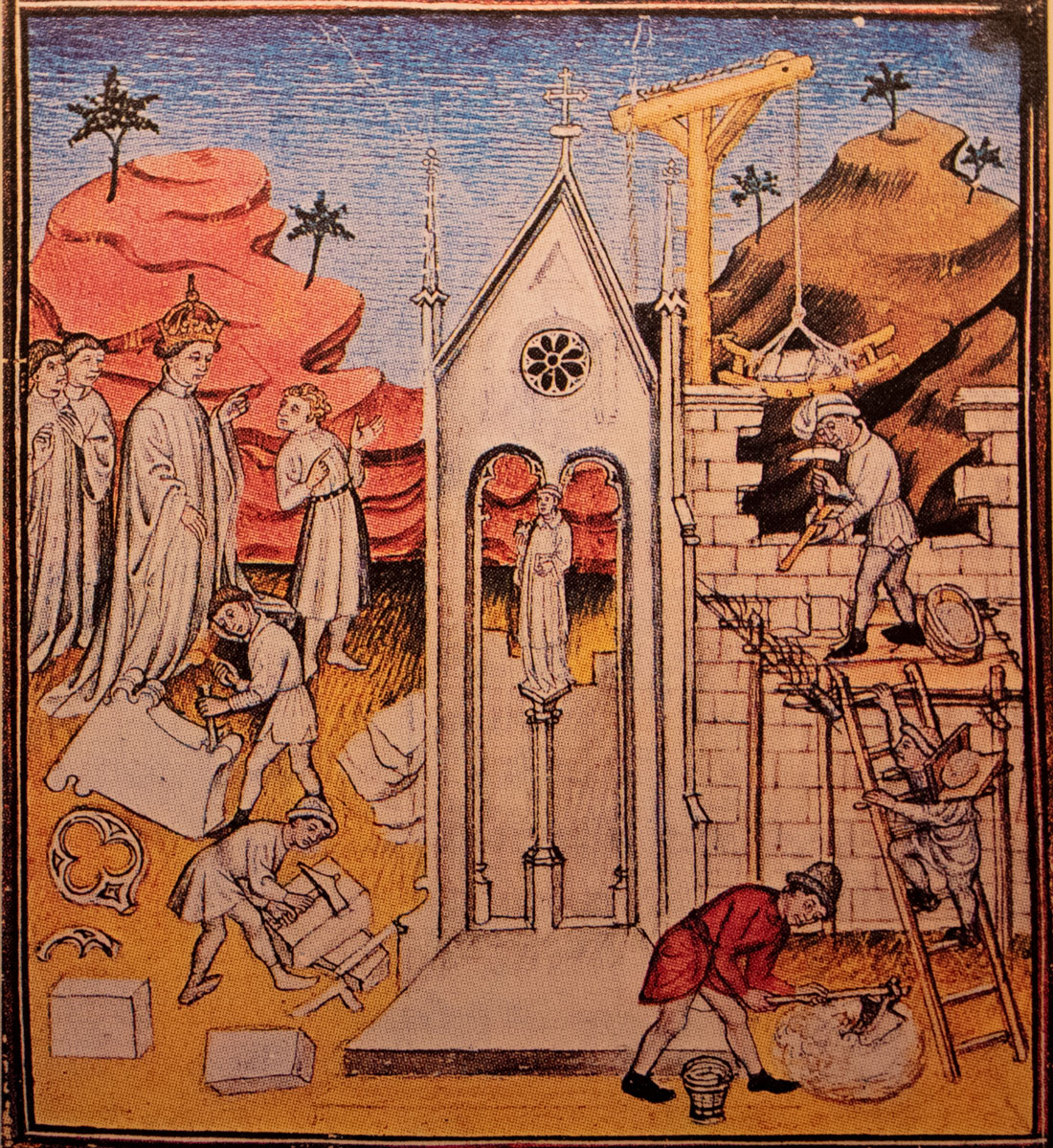

This model shows construction on the site of Notre Dame, with workers carrying out various tasks.

The work began at quarries where quarrymen without explosives or mechanical saws split the stones along cleavage lines in grain patterns in the stone beds. They shaped millions of tons of stone while surrounded by choking stone dust. They used harder stone for weight-bearing parts of the cathedrals and softer varieties for sculpture. The quarrymen were paid by the block.

The stones were transported to the building sites on barges or ox carts, each of which could carry a ton. A single cathedral would use thousands of tons of stone. In tribute to the sturdy oxen, 16 life-sized statues of oxen are on the towers of the cathedral in Laon, France.

Once in a while, there would be a shortage of oxen to move the stone. People would harness themselves to the ox carts and drag stones to the building on them as a form of religious penance for sins. At the site, they would beg the priests to scourge them as part of what came to be called the cult of the carts.

The masons drew inspiration from scenes from everyday life in the medieval world. Here, a horse-drawn cart was carved on a capital placed in the vault of Saint Denis.

A medieval depiction of stone masons working at a church construction site.

Working at a site in other capacities could be a form of penance, but it wasn’t appreciated by the workers who jealously guarded their wage agreements. Workers beat to death one penitent nobleman who was working on a cathedral for almost nothing. After the Black Death of 1349-51, stone masons’ wages went up because of a skilled labor shortage.

The masons shaped and marked on each block symbols indicating where it was to be placed on the cathedral. They also chiseled their personal marks or symbols on the stones to ensure that their work would be counted so they could be paid for it at the end of the week. Mason’s marks were passed down to sons, who would add a new stroke to them to distinguish them from their fathers’ marks. Researchers have mapped the travels of some masons from cathedral to cathedral using the marks.

There were different types of mason’s marks:

- Peacemaker’s marks. These ensured a stonecutter was paid for his work.

- Positioning marks – squares, crosses, or arrows – indicated the direction stones were to be placed.

- Marks of provenance identified the quarries where stones came from, so quarries could be paid, and stones could be arranged according to the quarry they came from.

- A master’s mark was given to a mason by his peers and was a unique identifier for the rest of his life. It was a sign of honor for outstanding work. Some of these marks became coats of arms which were inscribed on stones.

Many marks were simple crosses, circles, or letters, while others were elaborate. Some depicted animals.

Such marks were not unique to masons; local officials, nobility, and members of other craft guilds also had such marks, and carpenters and smiths placed their marks on their work.

The masons worked with other craftsmen to build churches. Smiths at the building sites sharpened and forged the masons’ hammers, chisels, saw, drills, punches and other tools, forged chains used to hoist stones, and created the giant nippers or tongs that gripped and lifted the stones high in the air.

The simplest stones were rough blocks that filled interior walls and buttresses. Apprentices shaped these. Journeymen cut the larger blocks for the face of the cathedral, drums stacked in columns, and stones that formed arches. Master masons cut the lacelike tracery on Gothic windows, carved moldings, and capitals for columns.

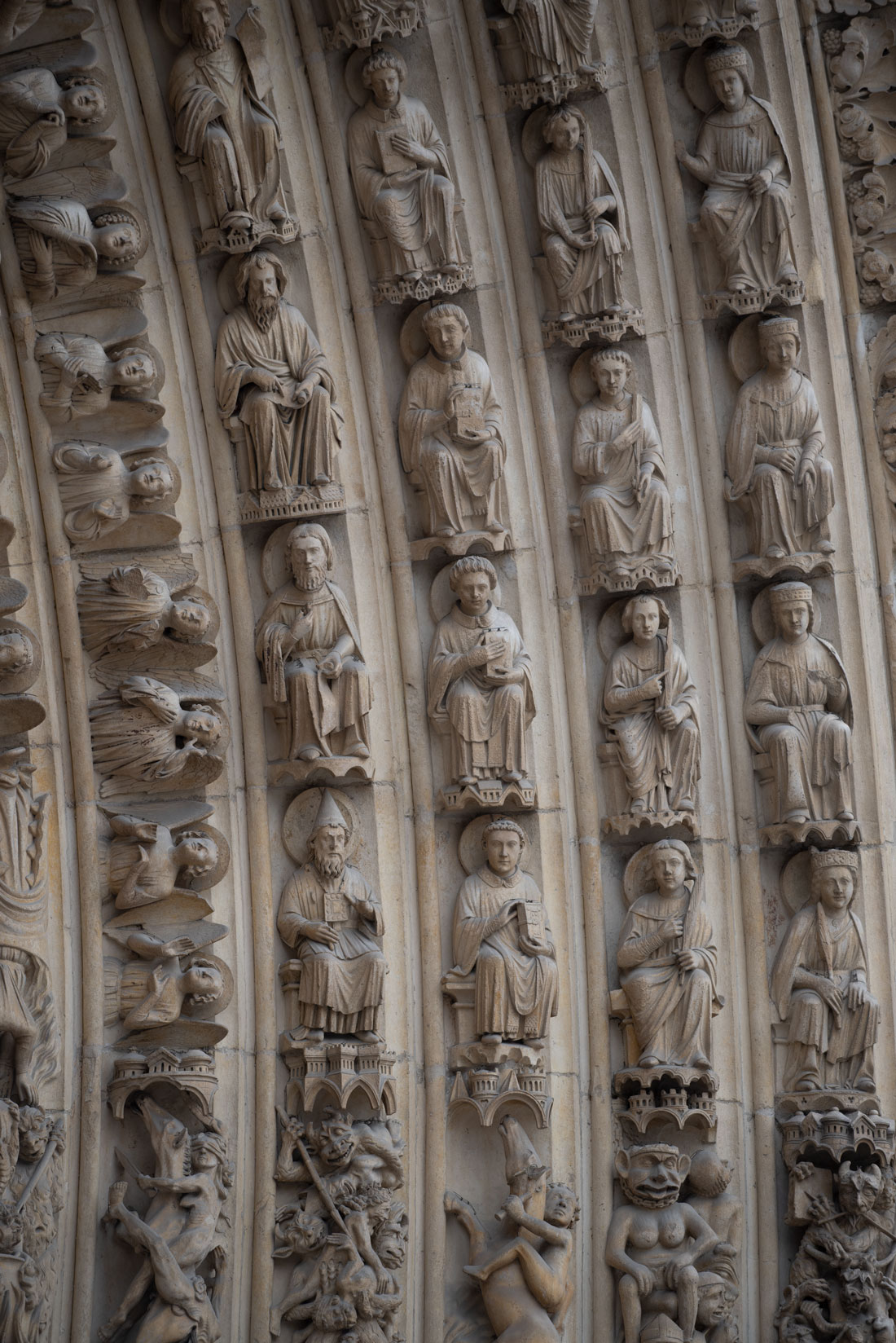

Those who carved the statues of the Virgin Mary, Old Testament figures, kings, angels, and gargoyles were among the most skilled. They had a huge job - Notre Dame has 1,200 sculptures, and the cathedral at Reims, France, has 3,000.

Sculptured figures on the facade of Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris, France.

The masons often carved buildings on the buildings as part of scenes such as this one of the Last Judgement on the facade of Saint Denis, Paris, France.

At Sainte Chapelle in Paris, a castle that was a symbol of King Louis IX's mother, Blanche of Castile, was paired with the royal fleurs de lis symbol of the French monarchy.

The masons lived at masons’ lodges, which housed architecture libraries, schools to teach apprentices, and also acted to protect mason’s rights and as a social and employment network for the masons.

The masons collectively discovered a series of architectural innovations that created the Gothic style, such as a thin-shelled stone web with a double curvature could be applied between the stone ribs on vaults. In some cathedrals, this is a thin mixture of stone rubble and mortar. The ribs supported it while it set. Much later, when some cathedrals were bombed in wars, it was discovered that their vaults would hold even if the ribs fell because of this thin mixture. The six-inch layer at Notre-Dame below held for eight centuries.

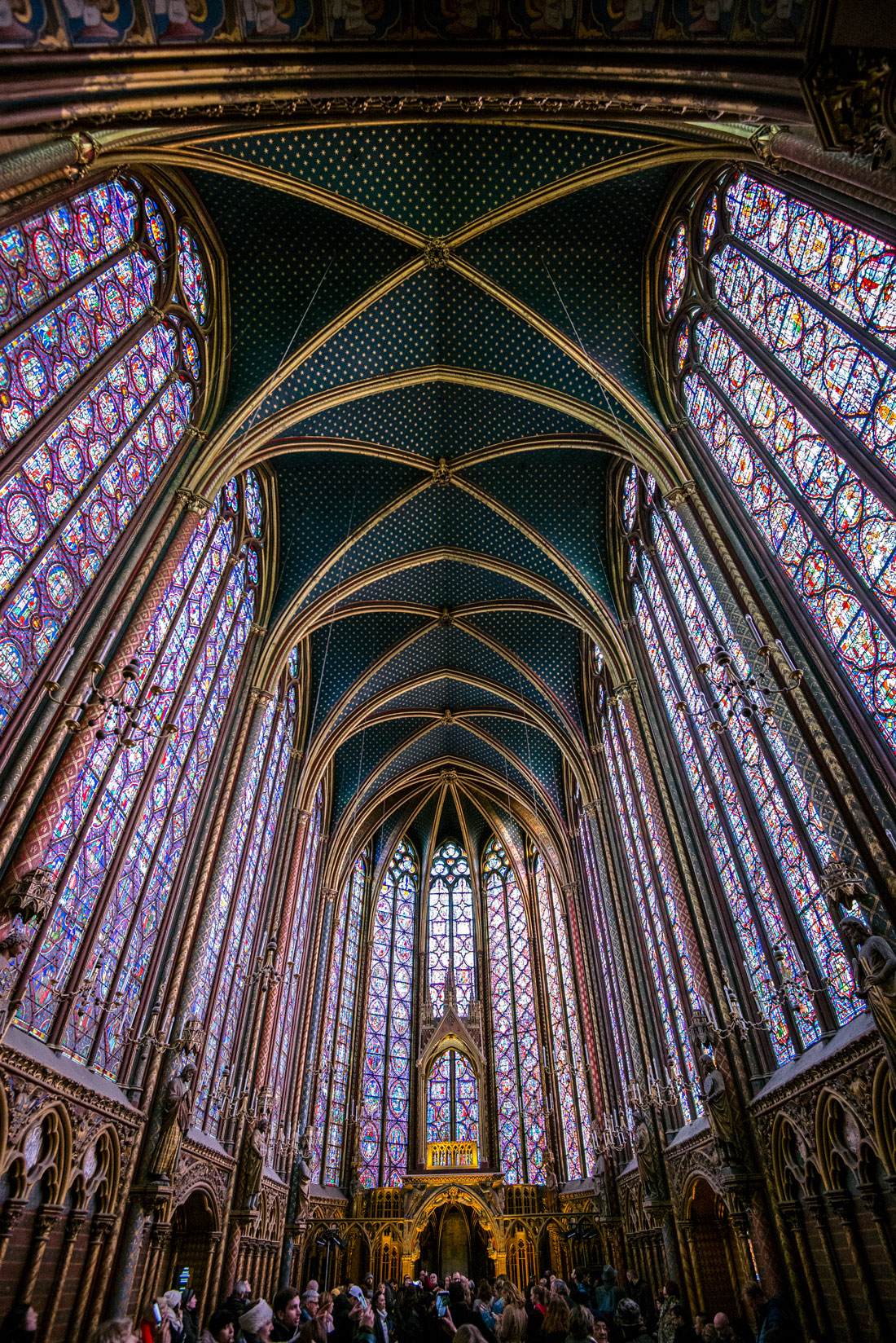

The vaulted ceiling above of Saint Denis, and below of Sainte Chapelle.

The masons’ lives depended on carpenters who lashed together the scaffolding used to build Gothic structures. For medieval people, scaffolding was one of the most common features of medieval views of cathedrals.

Carpenters also built ramps to carry materials, and shoring to hold walls in place as they were being built, and mortise-and-tenon roof rafters with wooden pegs.

Carpenters built and maintained a giant wheel for hoisting stone and other heavy items into place.

The carpenters also built complex curved frames that supported arches during construction. Unless the curvature of these was correct, the stone arches would collapse when the frames were removed. It was critical to remove the framing at the right time. If it were removed too soon, an arch would fall. If it were removed too late and the mortar was already hard, the vault would crack when the frame was removed and the building settled. The carpenters removed wedges a few at a time so that the arches could settle gradually as the mortar hardened.

A magister opris, or master of the work, directed construction on-site. He was a combination architect, general contractor, and foreman. He drew the plans, made models of the church, decided the order in which construction occurred, and negotiated costs with church officials. His position was high status – he wore an ermine robe and carried his gloves in his hand to symbolize that he was from the mason’s guild but worked with his head instead of his hands.

Contracts with masters of the work indicate that they were in high demand, were well paid, and had a clothing allowance, free food, and housing. They ate with the church monks or canons but got more to eat and could eat in the kitchen on fast days during which the monks presumably had to abstain from food. The masters, who had been educated in monastic schools, could read, write, and speak Latin which was the language of the church.

They typically had started as apprentices and worked their way up as journeymen and master masons before reaching the top.

The masters used as tools a set of compasses, a set square and a staff or rope marked off in halves, thirds, and fifths. The compasses and square were considered sacrosanct, and the masters carried them with them at all times. The masters had such a keen sense of proportion, geometry, and understanding of the capabilities and properties of the material they used that their work seems magical. Their cathedral designs were such fantastic, gravity-defying concoctions that some were thought to have gotten the building plans from the devil.

Gothic architecture first appeared in the 12th century and evolved for 250 years. Some cathedrals took hundreds of years to finish, so they had a succession of masters of the works. It was a dangerous job, and some masters fell from scaffolding while inspecting parts of cathedrals and died or were permanently incapacitated. Some were crushed by parts of buildings that collapsed on them.

Stone masonry had been widely used during the Roman Empire, but its use declined in favor of wood until the 10th century. It peaked during the Gothic building era of the 12th century.

The great cathedrals of that period, now hundreds of years old, are still used for their original purpose. This is an outstanding legacy for these masters whose genius was in blending immense size with balance and exquisite detail.

Masons often worked by candlelight on scaffolding to complete sections of the cathedrals on deadlines.

The master builders had a vast knowledge about selecting materials, managing workers, geometric proportions, load distribution, design, the Catholic liturgy, and Christian tradition.

Intent on imparting the message of the glory of God, they combined these elements in spectacular architecture which they embellished with sculptures of scriptural figures, influential contemporary leaders, and fictional creatures.

Often a plaque in the center of a cathedral is an image of a master mason holding a compass or a symbol of a compass and a square.

An inscription at Notre-Dame Cathedral says: “Master Jean de Chelles commenced this work for the Glory of the Mother of Christ on the second of the Ides of the month of February, 1258.”

The buildings created by these masons are among the greatest architectural treasures in the world. People flocked to them in medieval times, and still travel by the millions to France to see them.

Abbot Suger wrote that he felt as though he were being transported upward into the celestial heavens, the “Heavenly Jerusalem,” when standing in the rebuilt Saint Denis.

Notre Dome de Paris' exterior.

The medieval world was one of professional guilds for craftsmen, merchants, and entertainment. The guild system had existed since at least the Roman era, but became more prominent in the 11th century because towns and cities grew. Towns with cathedrals often were important market towns, and guilds joined with the church and government to build them. Markets sometimes were held close to the cathedrals which marked the center of town. Shops grew up around the market areas and cathedrals. It was in the economic interest of merchant guilds to support the building of the cathedrals, as they drew pilgrims who became their customers.

Skilled craftsmen in medieval towns worked in family workshops in neighborhoods devoted to their craft. Masters of the workshops trained young people via apprenticeships, regulated competition in their industry, and promoted their town’s prosperity. Guild members would agree on quality standards and policies that governed their specialty. The craft guilds developed large, sophisticated networks and associations. Some towns became renowned for producing high quality work in a particular specialty, and some towns in France still are known for such crafts.

The master of a workshop fed, clothed, and provided shelter for apprentices, who usually served him for five to nine years. An apprentice then could become a journeyman who continued to work for a master but received wages.

Stone masons had their own regulations, which usually weren’t written down because their training was done verbally. In France, the masons were secretive about their standards and skills. These secrets were considered critical because a mistake could cause a building to collapse and cost lives. It was part of the honor code of masons to keep these standards secret. A mason who revealed the secrets to a non-mason could be physically attacked by the other masons.

The masons were religious, holding services at the churches and maintaining and repairing church altars.

Journeymen provided proof of their technical and artistic skills by showing a master what was called a “masterpiece.” If it were approved, the journeyman could become a master mason, set up his own workshop, and train apprentices. Master masons were skilled, wealthy, and respected. Their status was reinforced with their secrets and initiation rites.

Apprentices vied to be trained by the best master masons in a highly competitive process, as masters accepted only two or three apprentices per year and some apprenticeships were hereditary.

Medieval guilds introduced new inventions, processes, and ideas. They worked with other craft guilds and with merchant and other guilds that financed parts of the churches.

Church building sites had a mason’s lodge where masons cut many of the stones, stored their tools, and ate lunch. Intricately carved stones and statues were created in the mason’s lodge.

Close or attached to the mason’s lodge was a tracing house where the designs were drawn. The designs for a building were worked out at full scale on tracing floors covered in soft plaster. The tracing floors still survive at Wells Cathedral and York Minster in England. Sometimes masters also made drawings on parchment. The drawings and the cathedrals themselves testify to the high expertise of the masons in geometry.

All stones were carved on the ground before being set in place. Larger blocks were carved at quarries so they were lighter and easier to transport.

Stone masons were given work clothes – hoods, gloves, boots, straw hats, and a robe. Most construction was done during the spring and summer months, and the mortar was allowed to set and the stone to settle over the winter. Some of the stonecutters specialized in placing the stones in position. During the winter, the masons worked indoors designing and cutting the stones, using geometry

Masters of the works were the liaisons between the church patrons who financed projects, guilds, and craftsmen. They worked daily with patrons at the site. The master also joined in the work when there was a labor shortage.

Some masters of works worked on two or three major buildings at one time, necessitating writing into contracts that a master had to stay on site to answer important questions. Some had trained assistants and messengers on horseback that conveyed messages to address this communication problem when they were off-site.

In England and France, the patrons were mainly the Church, the king, and wealthy individuals rather than city officials.

The basic tools of a master mason were a square and dividers or compasses. A mason carried them with him at all times and considered them sacrosanct. When he died, he often left the tools to his favorite apprentice. The expression “tools of the trade” is believed to have come from medieval stone mason guilds.

The most talented stone masons went from one cathedral site to another, following a particular master of works. Journeymen also traveled to different sites to learn new skills. We don’t know which guilds were responsible for what parts of cathedrals in France.

Some of the same skilled journeymen’s organizations of stone masons, plasterers, glass and metalworkers, woodcarvers, and others still are operating in France.

The elitist master mason system was a career dead end for many journeymen, so they formed independent guilds.

Masons became associated with a variety of legends and Biblical stories, most closely with the building of the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. Some French guild experts think that a group called the Children of Solomon may have been involved in the building of Chartres Cathedral, several Notre Dame churches and the cathedrals at Reims and Amiens. A group called the Children of Master Jacques mainly built churches in southern France. They are decorated with a Celtic cross – a cross enclosed in a circle. Masonry had several patron saints.

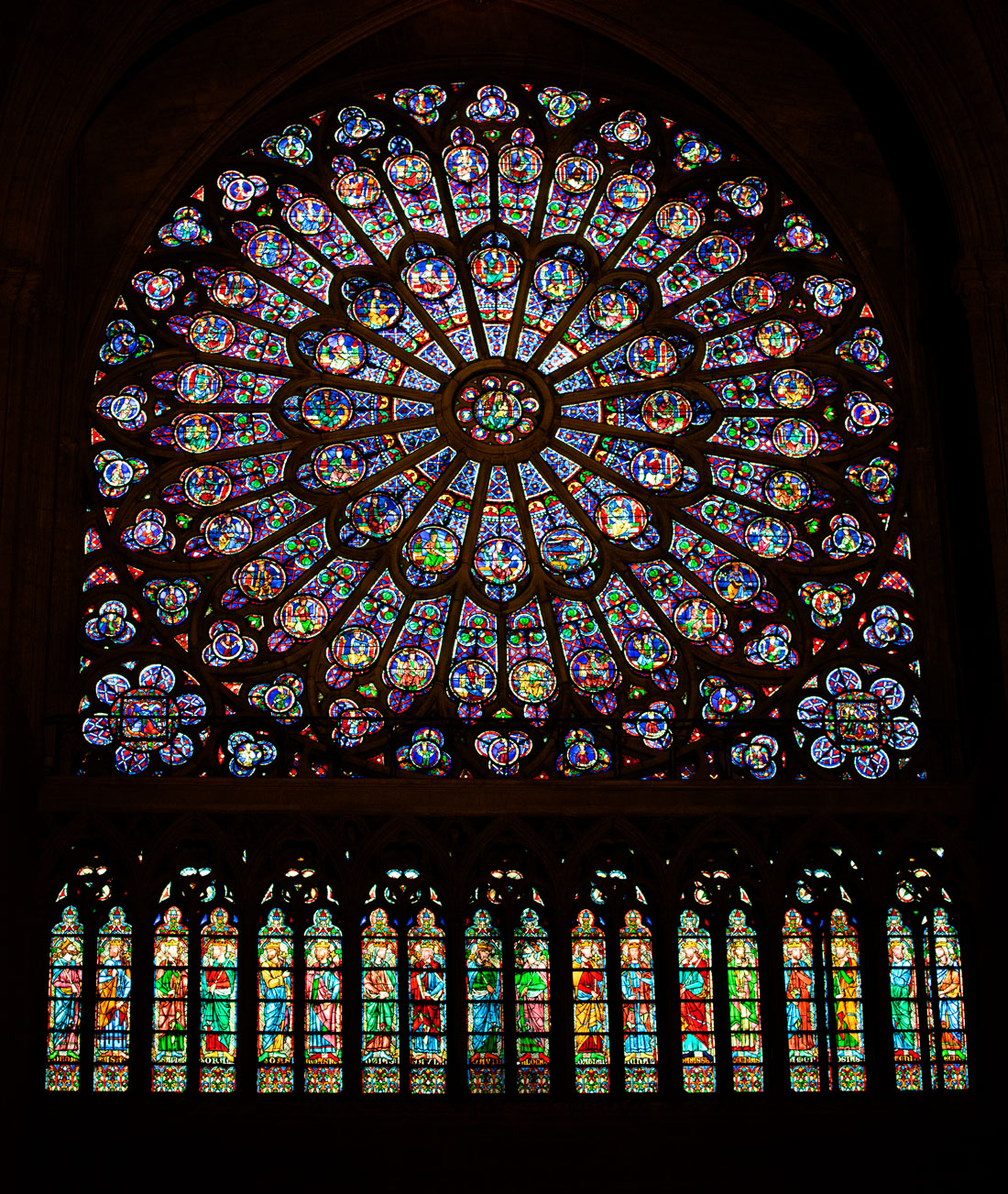

The medieval masons’ skill created miracles of 13th century architecture such as the rose window of the western façade of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. The window is thirty-two feet in diameter, with a design that is not only stunning in its stone lacelike tracery but has tremendous structural strength and weight that is so perfectly distributed that no cracks appeared in it in seven centuries.

When the cathedral was restored In the 19th century, the engineers of the time couldn’t equal the skill of the medieval masters, for whom Gothic style was the native architectural language. They worked in the style for generations, using stone almost as flexibly as steel is used in the modern world, ever pursuing more light, thinner supports, and the multi-colored stained-glass windows that became the hallmark of Gothic style.

As a result, a Gothic cathedral is alive with the brightly colored stories of the Old and New Testaments and the saints. They are a homage to the Creator, but also to the masons who created them.

Eventually, the stone masons’ rituals were adopted by the Freemasons, an influential fraternal organization to which George Washington, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, Gerald Ford, Voltaire, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and other influential historic figures belonged.

Early members of the Freemasons are thought to have been a guild of professional stone masons who adopted a liberal worldview as the result of their travels for work. They instilled moral and spiritual values into their members through their ceremonies. Their members advanced in the organization by symbolically rising from apprentices to journeymen to master masons.

The organization became known for its influence in promoting constitutional government and republicanism.

Today, the organization still exists and is engaged in various charitable endeavors.

A medieval depiction of Daniel in the lion's den on a capital, now in the Louvre, Paris.

Check out these related items

Paris’s Oldest Church Restored

Paris' oldest church, Saint Germain des Prés, is emerging from layers of grime and soot as a meticulous restoration reveals its vibrant color.

Saint Sulpice Church - Paris’s Temporary Cathedral

Saint Sulpice Church in Paris has a turbulent history dating to the 7th century. Today, it is Paris's temporary cathedral amidst the pandemic.

Scaffolding the World

Finding a historical site shrouded in scaffolding is disappointing, but it is a valuable tool for preserving the world's heritage.

The Panthéon of Paris

The Panthéon in Paris, France's national mausoleum, embraces the contradictory themes of the nation's turbulent history.

The World Mourns Notre Dame

Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris, France's national cathedral, was badly damaged in a fire.

Take a Break at the Louvre

Take a few minutes to stroll through the Louvre and rejuvenate your creative reserves.