Great Global Pandemic Bake Off

Photo by Forrest Anderson

Incensed home bakers who can’t get flour are venting on Facebook about the flour shortage. Some have lashed out at parents who are using flour to make Play-Doh for their kids while sheltering at home. Baking newbies are defending themselves on-line against angry veteran home bakers unable to buy flour, retorting that the veterans don’t have a monopoly on baking.

What’s going on here? Why is there a flour shortage in stores all over the world?

Welcome to the Great Global Pandemic Bake Off, which has emptied supermarket stores of flour and sent flour mills into overdrive.

Grain industry professionals say there isn’t an actual shortage of wheat, but the coronavirus epidemic has caused a major disruption in the supply chain. The flour industry is struggling to adjust to it.

In a pre-pandemic world, more than 90 percent of flour went from farm to mill and then into the professional food industry supply chain bound for restaurants, hotels and bakeries. The coronavirus collapsed that market because many of those businesses were forced to close or vastly curtail their businesses. However, the demand for baked goods containing flour didn’t go away. On the contrary, it jumped over to grocery stores as customers snatched up flour supplies and headed to shelter at home.

There, they have sparked the biggest home baking boom in decades. The flour industry has been struggling to reconfigure its supply chains to reroute flour supplies to consumers ever since. This consumer market was a small 4 to 8 percent of the market before the pandemic. The result of the disruption has been empty supermarket baking shelves and limits on how much customers can buy in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and a variety of other countries. Even in France, where there is a boulangerie on every urban street corner, people are baking at home. The flour shortage in Ireland has raised concerns about dependency on flour from the United Kingdom and brought to the fore talk about Ireland raising more wheat of its own.

Home baking had been declining for decades to record lows as had consumption of bread in general since women entered the workforce in the 1960s, so the sudden increase in demand was a big surprise. Fifty-four percent of food was prepared away from home by 2018. Per capita grain production had dropped from 146 pounds in 2000 to 132 pounds in 2018, U.S. Department of Agriculture data indicated.

With the pandemic, the trend dramatically reversed. In late March, sales of baking yeast soared 457%, flour sales went up 155%, baking powder sales rose 178%, butter demand was up 73% and eggs 48%.

Consumer surveys indicate that people who baked at home once a month now have started baking at home weekly, and those who baked weekly are now baking daily.

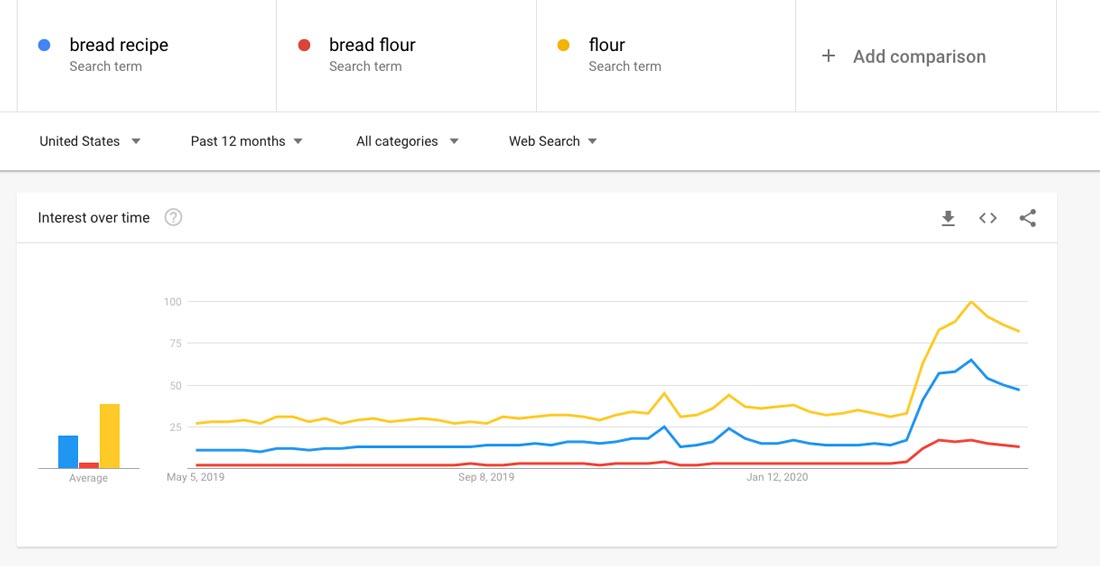

Online searches for bread recipes surged, according to Google Trends. BBC Food has experienced record traffic, including a 540% increase in traffic to its banana bread recipe and an 875% increase in traffic to its basic bread recipe. A page on how to make bread without yeast or bread flour has also soared in popularity.

Why? People who don’t want to go out to buy fresh baked goods as the coronavirus spreads have bought extra flour so they can weather the pandemic at home. They are cooking and eating at home instead of going out. Many are baking at home to save money as they are concerned about layoffs, and many are baking as a pastime.

Home baking is psychologically a comfort food which helps people build a sense of structure, sanity and security into their lives in a globally insane situation. It helps push back the panic. It also helps keep children who are sheltering at home occupied. A 2016 psycholological study indicated that baking can help people feel happier and like they are improving a basic life skill and growing personally. Baking has become a popular topic around which people can communicate on social media, with tens of thousands of posts on hashtags #quarantinebaking, #isolationbaking and #lockdownbaking.

The process of home baking plus the results lend structure, sanity and comfort to many people's lives.

“All bread bakers feel united. People are baking bread in many different languages,” Nigella Lawson has noted.

Bread holds an incredibly important position in many cultures. Bread shortages were notorious for their contribution to the French Revolution and the English bread riots of the 1790s. The grain supply in China historically has been closely linked to the ability of emperors and later Communist leaders to maintain their authority. Bread has a central sacred role in Christian, Jewish, Muslim and other religious traditions worldwide. Historically, laborers spent half of their income on bread so that when prices went up or supplies dropped, unrest increased. Some cultures historically had severe punishments for bakers who laced their bread with sawdust or chaff. Brown bread was associated with poverty and white with luxury until the 1960s when cheap white processed bread became the norm.

In national crises, flour and bread have long been among the first foods to be rationed and hoarded. My family never felt the pinch of rationing in World War II because a family matriarch had stored several hundred pounds of flour and sugar in her cellar before the war so the family had ample stores to supplement what they could get with rationing coupons.

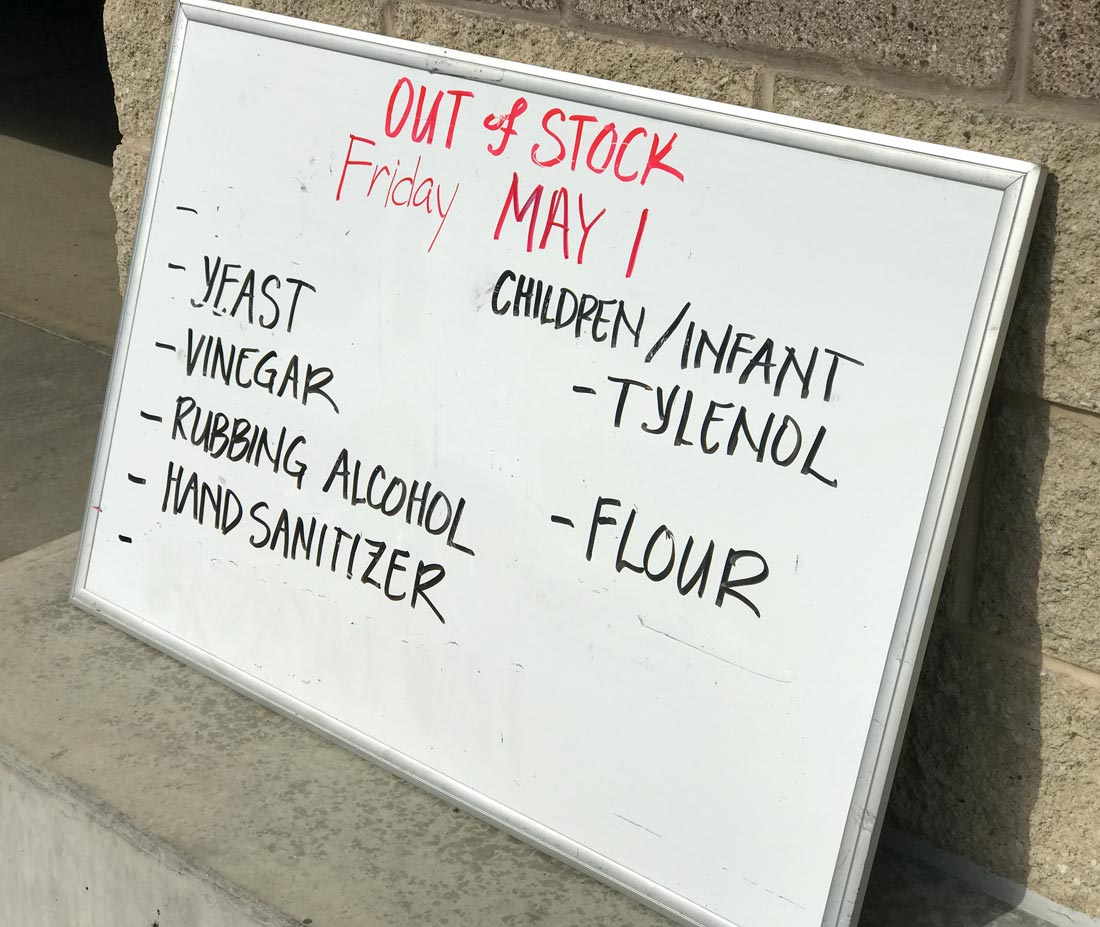

The new demand hit flour companies like a ton of wheat and caused immediate shortages as people stocked up on flour. Food stores took to putting up signs in the front telling consumers when they didn’t have flour, yeast and other items available or that customers were limited to one or two packages. When stores did get flour in, it often was in 50-pound wholesale bags.

A sign outside a Costco this week.

King Arthur Flour has had three times the normal sales for this time of year. It and many other flour mills are running 24/7 and hiring to keep up with the demand in addition to trying to implement social distancing procedures at their plants.

Small local flour mills have been slammed by orders from home bakers. Many are part of regional supply chains that include farmers and craft bakeries, and they are accustomed to putting out fine-quality flour in relatively small amounts on mills that run slowly. Some breed wheat especially for its high-quality taste. These small and midsized mills are part of regional supply chains have been built up by groups of farmers, processors, advocates, artisan bakers and chefs over the past couple of decades. The mills’ on-line orders for flour have gone through the roof, after first plummeting 95 percent because restaurants and bakeries closed. The mills have flipped the switch to producing for the booming consumer market. The scarcity means people are willing to pay more for fine quality flour. Many are finding that the flour produces the most delicious bread and other baked goods they have ever eaten. One small mill in the United Kingdeom found itself slammed with 10,000 orders online overnight. Some mills have had to close down their online shops because they can’t keep up with the demand, but their phones are ringing off the hook.

Many consumers are experimenting with a variety of flours made from different types of wheat and finding that they like them.

GrowNYC, an environmental nonprofit that operates farmers markets in New York City, sold 90,000 pounds of organic whole grains, flours and beans in 2019, but 38,000 in just the first three months of 2020. For the year, this could mean a 50 percent increase. Kentucky Finest, which sells on Etsy, has gotten hundreds of reviews for its flour.

Some mills are continuing to sell flour to local bakers who package and resell it to consumers.

The sudden surge took flour mills by surprise because home bakers usually don’t bake as much in the winter as spring. The demand this year has been twice that of the normal winter holiday season which is the annual peak.

The United States has abundant wheat supplies, according to industry professionals, but the bare supermarket shelves represent a problem getting the flour to supermarkets as fast as people buy it. They say the bottleneck is temporary. Mills in Europe, Canada, the United States and other places have been milling flour 24 hours a day seven days a week to double their production, but they are getting five times as many orders as normal so flour is still flying off the shelves.

The Sturminster Newton mill in Dorset, England, which has been around at least since 1016, has resumed commercial production after a hiatus of 50 years. The mill, with equipment from the Middle Ages, stopped producing commercial flour in 1970 and became a museum where flour milling demonstrations were held for the public. The museum had to close because of the lockdown, but then began producing flour for local businesses from the summer grain supply that it kept on hand for demonstrations. After that grain was used up, the mill acquired more. Its millers are working behind closed doors and with social distancing.

The 300-year-old King Arthur Flour company has shifted its labor force to new tasks. It is buying bread and other baked goods from its customers and distributing them to food pantries, homeless populations, unemployed foodservice workers and other people who need the goods. The company also has a baking series on Facebook called Martin Bakes at Home. Some employees are sewing cloth masks for health care workers and essential workers at the King Arthur Flour facilities.

The company suspended international shipments and next-day and overnight shipping options to streamline its workflows. Orders don’t leave the warehouse until all of the purchased items are in stock, which reduces the number of deliveries necessary to complete a customer’s order, the number of packages generated and the length of time it takes to get orders out the door.

Camas Country Mill in Junction City, Oregon has gone from 30 orders a week to 50-60 per day, with 80 percent from new customers who can’t find flour at the stores. Some employees at these small mills say the mills have been able to adjust better because they have short regional supply chains. Many companies along the supply chains are still scrambling to figure out new business models. Some have suggested a return to the old-time practice of a bakery truck delivering bread door to door.

The shortage has meant that many people have been able to buy flour, but not necessarily bread flour. They have gone home instead with all-purpose, self-rising, whole wheat or other flours. The key to success with these flours is to find a recipe that contains the type of flour you have on hand.

I was a monthly home baker who usually baked sourdough bread and pizza once or twice a month but am now baking weekly. I also have been very busy during the pandemic. As a result of this time crunch and of not always being able to get bread flour, I have simplified my bread making down to this no-knead bread recipe which is forgiving of all-purpose flour and uses only a small amount of yeast. I mix it up before bed and then bake it the next day.

No-Knead Bread

Ingredients

6 cups bread flour

2½ tsp. fine sea salt (this helps the bread have great flavor)

½ tsp. active dry yeast

2 2/3 cups cool water (sometimes the dough is dry and I have to add a bit more)

Cornmeal or added flour for dusting

Directions

In a large mixing bowl, mix together with your hand the flour, salt and yeast. Add the water and use your hand to mix for 30 seconds, creating a wet, sticky dough. Cover it with a towel, plate or plastic wrap and let it sit out of direct sunlight for 12-18 hours until it is bubbly and doubled in size.

Dust a work surface with flour, pull the dough out of the bowl and cut it into two loaves. Flour your hands and lift the edges of the dough toward the center to make each dough rounds.

Place a large dish towel on your work surface and dust it generously with cornmeal or flour. Gently lift the dough onto the towel seam side down and dust the top with cornmeal or flour. Cover the loaves with another towel and let it rise for 1-2 hours. Poke it and if the impression of your finger stays, it is ready. If not, let it rise for 15 more minutes.

After it raises for 1½ hours, preheat the oven at 475 F with a covered heavy cast iron pot in the center of the rack.

Carefully remove the hot pot from the oven, and lift one of the loaves. Gently place it in the pot with the seam side up. Cover it and bake it for 30 minutes, then remove the lid and keep baking it for 15-30 minutes until it is deep brown (I usually bake it for 20 minutes, but different ovens produce different results, so you have to experiment).

Then carefully lift the bread out of the pot (I use large tongs and am careful not to puncture the crust with them) and place the loaf on a rack to cool thoroughly while you place the other loaf in the pot and bake it the same way.

Resist the temptation to cut the loaf or tear off a slice until it has cooled for an hour.

You can freeze one loaf after it is cooled and thaw it when you need it. I wrap the loaf in aluminum foil and then place it in a gallon zipped plastic bag to freeze it. I take it out of the freezer and let it thaw over several hours before using it.

My advice during this stressful time is to stick with a simple, versatile, good tasting bread like this one as your base loaf. Then add grated cheese, chopped nuts or seeds, chocolate chips or other variations to the basic dough if you want variety. My favorite variation is to beat up an egg white and wash it over the loaf, then sprinkle it liberally with sesame seeds before popping it in the oven.

As far as working with different types of flour, here are my tips:

Avoid gluten-free flour if you don’t need to have a gluten-free diet, to leave gluten-free flour on the shelves for people who can’t eat gluten.

Pastry flour doesn’t work well alone for yeast bread, but you can blend it with other flour.

Whole wheat flour works best in bread recipes that specifically call for it. To use it in sourdough, feed it to your sourdough starter a couple of times and then use it in a whole wheat sourdough recipe. I sometimes combine white and whole wheat for a lighter bread.

If all you can find is rye flour, make a dark, moist bread like pumpernickel and slice it thin. Use it for sandwiches with cheese and ham or cold cuts.

Semolina flour makes good semolina bread.

People who have found flour have complained about yeast being difficult to get, hence the huge trend of people making their own sourdough starter.

Yeast has faced a similar supply problem as flour, as most yeast was similarly part of a supply chain that went to restaurants and bakeries rather than grocery stores. The demand for yeast jumped 410 percent for the four-week period ending April 1. It quickly sold out at grocery stores and a 2-pound package of Red Star Active Dry Yeast briefly sold on-line for $48.95 before the price dropped down to $19.99.

Fleischmann’s yeast had a yeast inventory when the pandemic began, but it sold out almost instantly and the company has had to hire and train new workers to ramp up production.

Yeast is a single-cell fungi that grows when fed with carbohydrates and nutrients, is filtered, dried and packaged. The process is a natural one that can’t be hurried up and production takes about ten days. Then the package and supply chain has had to be adjusted to reroute yeast to grocery stores. The major problem has been packaging yeast when the materials for paper packets are in short supply and the factories where yeast jars are made have closed because of the coronavirus.

In the midst of the rampup, yeast plants have had to take measures to protect their employees from the coronavirus – checking their temperatures, installing plexiglass shields between workers and distributing protective equipment to them.

The yeast shortage has resulted in some heart-warming and humorous moments.

One woman who worked as a caterer was laid off because of the pandemic. People began donating small amounts of yeast to her so she could continue baking, and she is now selling dinner rolls, hamburger buns, sandwich breads and sticky buns on Instagram.

A Boston yeast geneticist named Sudeep Agarwala became a minor celebrity after he attended via video a birthday party at which a guest complained that she had bought a breadmaker but couldn’t find yeast. Agarwala laughed because yeast is ubiquitous in the environment. Yeast are creatures that live and reproduce in the air, on produce and on skin. All you have to do is capture it. The next day, he tweeted on Twitter, “Friends, I learned last night over Zoom drinks that y’all’re baking so much that there’s a shortage of yeast?! I, your local frumpy yeast geneticist, have come to tell you this: THERE IS NEVER A SHORTAGE OF YEAST.”

“Here’s where I’m a Viking,” he wrote. “Instructions below.”

Agarwala’s recipe:

Find some dried fruit in your kitchen, like raisins.

Put tablespoon or so of the fruit in a jar with about three tablespoons of water. Stir it around. The water’s getting cloudy. That’s yeast coming off the fruit.

Mush in three or four tablespoons of flour until it is the consistency of wet dough.

Cover the jar loosely with a lid and find a warmish place to put it. Around 70 degrees is right.

Agarwala’s instructions were retweeted 27,900 times.

“My heart belongs to yeast,” said Agarwala, whose job is to research yeast. “I apologize for being a nerd here, but it is actually incredible to see this dust you put into warm water, with a little sugar (from the fruit), and all of a sudden you see this … bloom. To this day it makes me smile. It’s a bit of a miracle.”

The story doesn’t end there. People started sending Agarwala photos of the bread, focaccia, cinnamon bread, pancakes that they had made using his yeast instructions.

“It is so rare that I get to feel this useful in my life,” Agarwala said. “People are making the most spectacular loaves of bread.”

Agarwala’s recipe is similar to sourdough starter except for the fruit. Sourdough starter is usually made with a mixture of flour and water that you leave for a week or so and add a little flour and water to daily until you have bubbles which show that it is growing. If you feed it, you can keep it alive for generations, share it and pass it on to your heirs. I once had a sourdough starter taken from a friend's 100-year-old starter. I kept and used it for ten years until it sadly was destroyed during a family move.

The Global Sourdough Project invited respondents to send samples of their sourdough starts to a study lab at Tufts University with information about their starter. Within a week, they had received 80,000 words of information from respondents.

A downside of home baking is that some people are reporting that they are gaining the #quarantine15 or quaren-ten. For other people, though, being away from restaurants and social events has helped with weight loss, so chances are this aspect is a bit of a draw.

Check out these related items

Inventory App and Sticker Dots

Use sticker dots and an easy inventory app, Enough Stuff, to keep track of your food supplies, toiletries and other stuff of all kinds.

Creating an Easy Cooking System

Creating a simple, versatile cooking system can enable you to serve delicious meals at home even on days when you are swamped.

Store What You Eat Guidelines

The pandemic has been a major wake-up call about planning, home storage and preparation for crises. Here are some guidelines.

Eating Food in Season

Eating locally grown food in season is a great strategy for weight loss, good health, saving money and protecting the environment.

Beyond Recipes

Beyond the world of recipe-based cooking is an adventurous, affordable, easy way of cooking that combines the basics with variety.

The World is Flat (Bread)

Flatbreads are oldest, easiest breads and the most modern - pizza and tortillas are among the most popular foods. See our recipes.