The Land of Junipero Serra

Photos by Forrest Anderson

We have seen Indians in immense numbers, and all those on this coast of the Pacific contrive to make a good subsistence on various seeds, and by fishing.

— Junipero Serra

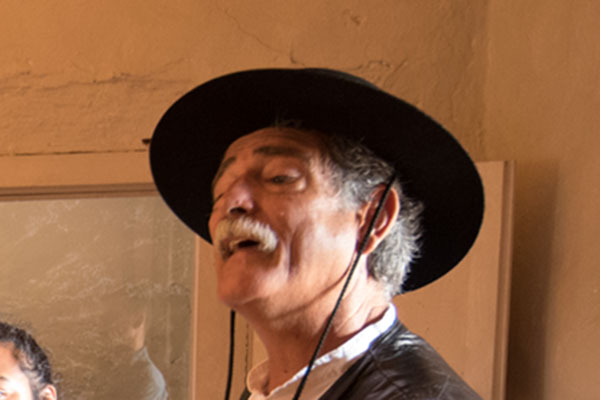

Statue of Junipero Serra at the San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo Mission, Carmel, California. Above video, the ringing of the bells at the Old Mission Santa Inez in Solvang, California.

Many Californians raised an eyebrow when Pope Francis canonized as a saint Franciscan priest Junipero Serra on Sept. 23 in Washington DC. Serra’s status as one of the most influential founding fathers of the land that became the United States’ largest state is beyond doubt. However, Serra’s sainthood is controversial, largely because of the impact of his career on the native population of California.

Serra, a Spanish Franciscan, founded the first nine of the 21 Spanish missions that dot the Camino Real from San Diego to San Francisco and laid the foundation for the building of the others. As such, he probably did more than any other man to determine the character of California culture today.

The missions, most of which survive only partially or in a restored form, are America’s most-visited historic sites. Their architecture is the main influence behind the Mission Revival architectural style, which permeates architecture all across the American southwest, Florida and in warm seaside locations all over the world. The style has left its alluring mark along the coast of California on buildings from churches and government buildings to fast food places and super markets. The style has its roots in Spanish Colonial buildings derived from Renaissance and Baroque architecture in Spain.

As seen today, the cream or coral-colored adobe walls, bell towers, thick arches, courtyards, long exterior arcades, clay tiled roofs and huge wood beams and doors of the missions appear ineffably calming, spiritual and comforting.

These two photos are of the San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo Mission, where Junipero Serra is buried.

This heavy arch at the Old Mission Santa Ines mission is typical of the arches on the long arcades in the missions.

My personal favorite of the missions is La Purisima in Lompoc, California, a Central Coast town where my mother lived. La Purisma was not personally established by Serra, but is part of the mission system he devised. We enjoyed walking around the mission, which in the late afternoon was bathed in warm red light. I am not Catholic, but after my mother died, I strolled through the mission seeking the comfort of its soothing spell.

La Purisima mission.

Families gather on Christmas Day at the Old Mission Santa Inez. Most of the missions are still functioning and services are held at them regularly.

However, part of the history of the California missions, like other beautiful colonial architecture around the world, belies their atmosphere of serenity.

Serra and the other priests who led the Spanish colonization effort in California had as their goal converting native Californians to Catholicism and integrating them into the Spanish empire as a way of securing California for Spain. To accomplish this, they subjected Native Americans to treatment that resulted in cultural annihilation and forced subjection to the mission system. In this regard, Father Junipero's legacy is mixed.

Serra was born into a Catalan farmer’s family in 1713 on the island of Majorca off the Mediterranean coast of Spain. Catholic friars educated him until he enrolled in a Franciscan school, where he became a Franciscan friar and later a priest. He left for a mission to Mexico in 1749. After training in native languages of Mexico, mission administration and theology, he was sent to his first mission post in Mexico. He learned to speak local languages and involved local parishioners in ritual reenactments of Jesus’ forced death march, erecting 14 stations past which he led a procession carrying a heavy cross. Some of California’s missions have stations like these today. Serra also took the role of Jesus in washing the feet of 12 local elders on Holy Thursday and dining with them.

He had cattle, goats, sheep, and farming tools sent to the mission and supervised native farm labor and spinning, sewing and knitting. Natives who adapted to his program received land to raise food on. Serra persuaded local people to abandon their worship of their goddess Cachum, the mother of the sun. In a dispute between Mexican soldiers and local people over land, Serra sided with the natives. The viceroy of Mexico ended up ordering the military to keep their cattle out of the native people’s fields and pay them fairly for their labor, with the friars supervising the payment. In 1755, the local people and friars reclaimed the land and the military settlers moved away. Serra oversaw the construction of a church in the mission area, carrying wooden beams and applying mortar between the stones of the church himself.

On the down side, Serra was an inquisitor during the Spanish Inquisition. He denounced several non-natives for witchcraft, sorcery and devil worship. He believed in corporal punishment as a disciplinary method for parishioners as well as himself. He was famous for wearing sackcloth spiked with bristles or a coat woven with broken pieces of wire under his friar’s cloak. He walked long distances in spite of painful leg and foot sores, and whipped himself with a chain of sharp pointed iron links when he had sinful thoughts. He would smash a stone against his chest until his listeners thought he was going to kill himself and burn himself with candles.

After Jesuit priests were expelled from New Spain in 1767, Serra was appointed president of 12 missions in Baja California developed by the Jesuits. Epidemics spread by the Spanish military when it entered the area to expel the Jesuits reduced the native population to about 5,000.

In 1768, Serra was appointed to head a missionary group to Christianize the native population of California and control the Pacific coast so that Russia couldn’t claim it. Spain had sought since the discovery of New Spain to establish missions to convert native peoples in Mexico and today's southwestern United States to Spain's state ideology, Catholicism, as a means of pacification and colonization. Serra’s mission effort to California was business as usual and represented Spain’s broadest reach in North America.

Serra's goal was to transform the natives into Spanish speakers and taxpayers and create a mission-based system that would control California's economy. This was no small task, as indigenous Californians of the time may have numbered as high as 300,000 in more than 100 separate tribes.

Franciscans saw Native Americans as children of God who would make good Christians and segregated them from non-Christian Native Americans. Converts were not allowed to come and go at will. The friars engaged in forced labor of converted natives to support the missions, but pushed for a legal system to protect the natives from abuse by Spanish soldiers. Serra shared the common Spanish attitude that the missionaries should treat their converts like children, including whipping them as punishment.

He has been criticized by Native Americans for imposing Christianity on the natives and damaging their culture reparably. Nonetheless, many Native Americans who are Catholic supported his canonization. Two members of the California Ohlone Tribe participated in the canonization Mass by placing a relic of Serra’s near the altar and reading a scripture in a native language.

An image of Christ at the Carmel mission.

Tens of thousands of Native Amerians were lured to join the missions by a desire to engage in trade, but trapped once they or their children were baptized because they were forcibly kept at the missions. Family members of converts joined the missions to be near their loved ones. The converts were guarded, herded to daily masses and labors and considered runaways if they went missing. Military expeditions were organized to round up the escapees along with other people in their villages and bring them to the missions. Epidemics brought by the Europeans killed almost half of the native population.

This monument eulogizes Christian converts who died at the Carmel mission.

Young native women were kept in nunneries and their marriages supervised by the priests. The crowded conditions in which they lived contributed to the spread of disease among them.

Bells were rung at mealtimes to call the residents to work and daily religious services. The women did dressmaking, knitting, weaving, embroidering, laundering and cooking and brick carrying. The men plowed, planted, irrigated, cultivated, reaped, threshed and gleaned as well as building adobe houses, tanning leather, shearing sheep, weaving rugs and clothing and other duties. Their labor was generally unpaid.

A loom at the La Purisma Mission.

Farmland adjacent to the Santa Ynes Mission. The missions once owned and cultivated large tracts of land.

From an economic point of view, the missions with their native populations were critical to keeping California within Spain’s political influence. The missions produced all of the colony’s cattle and grain.The missions brought the citrus industry, olive cultivation and curing and tobacco cultivation in California as well as cattle and sheep raising. These animals’ grazing and the spread of introduced invasive plants adversely affected some native plants upon which indigenous peoples had depended for food.

The mission system taught the Native Americans European agricultural and building skills. Natives built aqueducts, cisterns, grinding wheels and water purification systems and dug irrigation systems.

Serra originally planned to distribute the common mission lands among the native population within ten years after the missions’ founding, but found that this task took more time than he had anticipated. For the most part, it was not realized. The mission system endured between 1769 and 1833, after which the Mexican government secularized the missions and divided them into land grants that became ranchos. When the mission system was secularized, those who had lived on the mission lands were left without legal title to the land.

After 1826, all Native Americans in the military districts of San Diego, Santa Barbara and Monterrey who were found qualified were freed from missionary rule and were eligible to become Mexican citizens. Those who wished to remain in the mission system were exempted from most corporal punishement. By the early 1840s, the statewide native population had dwindled to about 100,000, a result of food shortages, disease, beatings, rapes and murders. The declines were the steepest in areas affected directly by the missions and the Gold Rush of the 1840s.

The surviving mission buildings are Calfornia’s oldest structures.

Serra founded the following missions personally, while the others in the chain of missions spaced a day's horseback ride apart along the Camino Real were founded by others of his order.

- Mission San Diego de Alcalá, in San Diego, and nearby Visita de la Presentación

- Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo, which he moved to Carmel in 1771

- Mission San Antonio de Padua near Jolon. The distinctive red tiles were first fired there.

- Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, in San Gabriel, California

- Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, in San Luis Obispo

- Mission San Juan Capistrano, in San Juan Capistrano

- Mission San Francisco de Asís in San Francisco.

- Mission Santa Clara de Asís in Santa Clara

- Mission San Buenaventura in Ventura

The mission system became the backbone of modern coastal California.

Serra died at age 70 in 1784 at San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo Mission in Carmel and is buried under the floor in the sanctuary. He was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1988 for sewing the seeds of Christian faith in the New World. Pope Francis in May 2015 said that "Friar Junípero ... was one of the founding fathers of the United States, a saintly example of the Church’s universality and special patron of the Hispanic people of the country."

On Sept. 27, the San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo Mission was vandalized in protest against Serra’s canonization. A statue of him was pushed over and the statue, parts of the mission cemetery, the mission doors, a fountain and a crucifix were splashed with paint. The message "Saint of Genocide" was painted on Serra's tomb, and similar messages were painted elsewhere in the mission courtyard.

Serra is considered the patron saint of California, Hispanic Americans and religious vocations.

Personal items belonging to Serra are on display in the mission museums and his papers are the earliest archival materials in the Santa Barbara Mission Archive-Library. A number of schools, Interstate 280, streets, trails and at least one park in California are named after Serra. His image has appeared on postage stamps in Spain and the United States and there are statues of him in a number of locations in California and elsewhere.

While the Spanish government was forced out of California, Serra’s cultural legacy remains pervasive in California. A quarter of California’s population speaks Spanish. Spanish names, architecture, cuisine and customs permeate the coast.

A third of Californians today are Mexican Americans and Mexican Americans make up 40 percent of Los Angeles and a large part of many other California communities. California now has 350,000 native Americans, but most are descendants of people who migrated to the state in the 20th century from other areas of the United States. The majority of Calfornia’s original tribes are extinct.

Sunset at La Purisima.

Related photos:

Santa Ynes

Check out these related items

What does it mean to be Hispanic?

What does it mean to be Latino or Hispanic in the United States? This blog explores the ambiguous origins of these two terms.

Why Isn’t Every Town Like Carmel?

Carmel, California, demonstrates how design, planning and environmentalism can enhance a small town.

The History of Race in America

The racial history of the United States belongs to us all, with the responsibility to resolve the accompanying outstanding problems.

Getting A Vaccine against Racism

A mother of non-white children compares her fears for her children because of COVID-19 and her fears for them because of racism.

California’s Danish Village

Solvang, California's Danish village, is the perfect place to take an afternoon stroll and enjoy pastries and art galleries.

Barbecue Santa Maria Style

Santa Maria's scrumptious grilling is California's premier barbecue style.