The Style that Went Around the World

Photos by Forrest Anderson

Most people think of Gothic architecture as medieval and European, but the majority of Gothic-style buildings were created all over the globe during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Neo-Gothic churches, town halls, parliamentary buildings, train stations, houses and even high-rises were built as cities from Ottawa, Canada, to Jakarta, Indonesia, and from Russia to Australia launched ambitious urban-renewal programs that still define city centers today.

St. Mary's Cathedral, Sydney, Australia.

There is evidence that Gothic style is having a third resurgence in the 21st century. The new interest in Gothic is driven by tourism to Gothic landmarks, films that highlight Gothic architectural settings and design, the ambitious restorations of medieval Gothic landmarks such as Notre Dame de Paris, Parliament in London, and Neo-Gothic churches such as St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, and the building of new Gothic-style churches in the United States.

St. Patrick's Cathedral, New York, which underwent a $200 million restoration in 2015-16.

The original Gothic architecture of the great medieval cathedrals of France, England and other European countries began with an expansion of the Basilica of St. Denis in Paris in the 12th century, spread throughout Europe and finally waned in the 17th century when Gothic churches that had been started much earlier were completed.

Some Gothic construction lingered on at universities such as Oxford and Cambridge and in the construction of rural churches as well as restoration of Gothic churches, but Europe had moved on through Neo-classic Roman-style architecture of the Renaissance and the Baroque style. The medieval religious fervor that had fueled the exuberant soaring craftsmanship of the Gothic era was diluted by the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Counter-Reformation and the subsequent emphasis on science.

England was industrializing, and hand-crafted Gothic arts were falling by the wayside. By the late 18th century, many medieval Gothic churches had fallen into a genteel state of ruin that had a nostalgic appeal to Romanticists who were appalled by the social and environmental side effects of the Industrial Revolution as well as the threat that it posed to the aristocratic power structure of England.

The rise of Romanticism brought with it a renewed interest in the architecture, stained glass windows and illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages. At the same time, a high church movement arose that tried to emphasize continuity between the Church of England and the pre-Reformation Catholic Church as a reaction against industrialization and the rise of evangelical religion. The high church movement used Neo-Gothic architecture to symbolize Christian values threatened by industrialization. The church wanted to build large numbers of churches to cater to England’s growing population, and proponents believed that only the Gothic style was appropriate for a parish church.

Some aristocrats hired architects and decorators to create colorfully decorated and furnished Gothic-style drawing rooms, libraries, chapels and turreted castles on their estates, in effect creating private idealized fantasies of the Middle Ages which they saw as a golden age.

By the 1820s, this Gothic revival had attracted the attention of architects who produced books with drawings of Gothic styles that became standard references for younger architects. They designed Neo-Gothic churches and public buildings. Based on Gothic motifs such as pointed arches, finials and pinnacles, the style influenced not just architecture, but light fixtures, furniture, fireplace facades, wallpaper designs and drapery.

Neo-Gothic followed the arc of the British Empire’s 19th century global peak, spreading out to European colonies worldwide and lasting long after the popularity of the style had faded in Britain itself. The Neo-Gothic style helped reinvent city architecture as monumental buildings such as the Parliament of Westminster in London and Tower Bridge and similar imitations from India and Azerbaijan to China were built. From 1847-1887, England minted British crowns with a Gothic Revival design that became known as Gothic crowns.

Parliament, the Neo-Gothic building that helped spread the British Empire's brand worldwide, has been shrouded in scaffolding for years as a long-term restoration project has proceeded.

Tower Bridge in London was built in Neo-Gothic style, but like many 19th century structures, it was a metal structure clad in Gothic stone and motifs. It was restored a few years ago.

The rebirth of Gothic in 19th-century France was political. Revolutionaries had looted and badly damaged French churches, including Notre Dame de Paris and Gothic masterpieces all over the country, during the French Revolution of 1789. When Napoleon Bonaparte rose to power, he negotiated a deal with the Catholic pope whereby the churches could be reopened for worship but remained the property of the state. The churches were in abominable shape, and some were demolished while restoration campaigns were launched for others.

Napoleon began an ambitious program to recreate Paris as a Rome-style capital for his empire. This urban renewal expanded after Napoleon was replaced by a restored monarchy that saw itself as a partner of the French Catholic Church in reviving France’s historical glory. This included the ambitious restoration of medieval Gothic churches and the building of new larger churches that could accommodate a growing urban population. Churches were reimagined as anchors at the ends of new public plazas and boulevards. The churches were filled with colorful Romantic paintings and statues aimed at driving home the message of the close partnership between the church and monarchy. Victor Hugo’s famous novel, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831), and his longstanding campaign to restore churches were part of this effort.

French architect and historical restorer Viollet Le-Duc was the towering figure behind French Neo-Gothic. He restored Notre Dame and other Gothic landmarks in France to multi-colored splendor, putting his own controversial mark on buildings such as the lower chapel of Sainte-Chapelle for which he had no historic reference material. His restorations have been the global image of French Gothic style in the minds of millions of tourists who have visited France since, to the point that the current plans to restore Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris after the 2019 fire that destroyed its roof aim to restore it to Le Duc’s era. This makes sense, as the original building took so long to complete – 200 years – that it would be hard to find a defining point in medieval times to restore the building to. Le Duc’s work, on the other hand, is familiar to those who love Notre Dame and much of it was undamaged and just needs cleaned and touched up.

The most prominent Neo-Gothic church in Paris, the Basilica of Sainte Clotilde, was built in 1846 and consecrated in 1857.

The 19th-century neo-Gothic Basilica of Sainte Clotilde, Paris, France.

In Germany, Neo-Gothic style was popularized by plans to complete the Cologne Cathedral, which had been started in 1248 but not completed. Finished in the 1880s, it was the world’s tallest building of the time. St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague, Czechoslovakia, started in 1345, also was completed in the mid-19th and early 20th centuries.

By the mid-19th century, Neo-Gothic architecture had become the preeminent architectural style in the Western world and had spread globally through western European empires, inspiring the Germans, French and English all to claim that Gothic architecture had originated in their countries and was their national architecture. Gothic buildings also were restored, completed or built in Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, Hungary, Bulgaria and other countries to express national influence and wealth. In rising colonial cities in India and Shanghai, China, Gothic-style buildings mixed with Neoclassical, Baroque and later Art Nouveau in city centers.

Neo-Gothic is far from the same style as the original Gothic. It is characterized by using the ornamental styles and principles of medieval Gothic but contemporary materials and construction methods, most notably the use of iron and steel. These materials enabled Neo-Gothic architects to break free of the constraints of using flying buttresses to balance the load of the roofs on a building’s walls, so that Neo-Gothic architects could create very tall buildings, even high rises. The 1913 Woolworth Building in New York City applied Neo-Gothic ornamentation to an iron skeleten. The Tower Life Building in San Antonio, Texas, even was given decorative gargoyles. Great prefabricated structures such as the glass-and-iron Crystal Palace incorporated such construction methods along with Gothic characteristics.

Gothic style inspired designers in many fields with its pointed arches, coats of arms, illuminated manuscripts, elaborate medieval scenes and furniture decoration. The Gothic interacted with industrial techniques to mass produce medieval-themed wallpapers, fabrics, furniture, carpets, and other items inexpensively so that middle-class people could decorate their homes with them. Silversmiths and other luxury goods artisans produced Gothic-themed products. It became popular in the late 19th century for wealthy people to dress in medieval-themed clothing for parties and reenactment fairs and festivals. Large metropolitan cemeteries were created in Gothic style, with chapels, gates and decorative features.

Neo-Gothic style continued to be popular well into the 20th century, with large numbers of Neo-Gothic structures built throughout the Americas, Australia, Africa and Asia.

Trinity Church, St. John’s Church, and St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York are among the most prominent Neo-Gothic churches in the United States. The Gothic-style National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., was begun in 1907 and not completed until 1990.

Trinity Church, New York City, New York.

In the United States, Collegiate Gothic style transformed college campuses from Princeton and Yale to the University of Pennsylvania and Duke University.

Gothic architecture at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina.

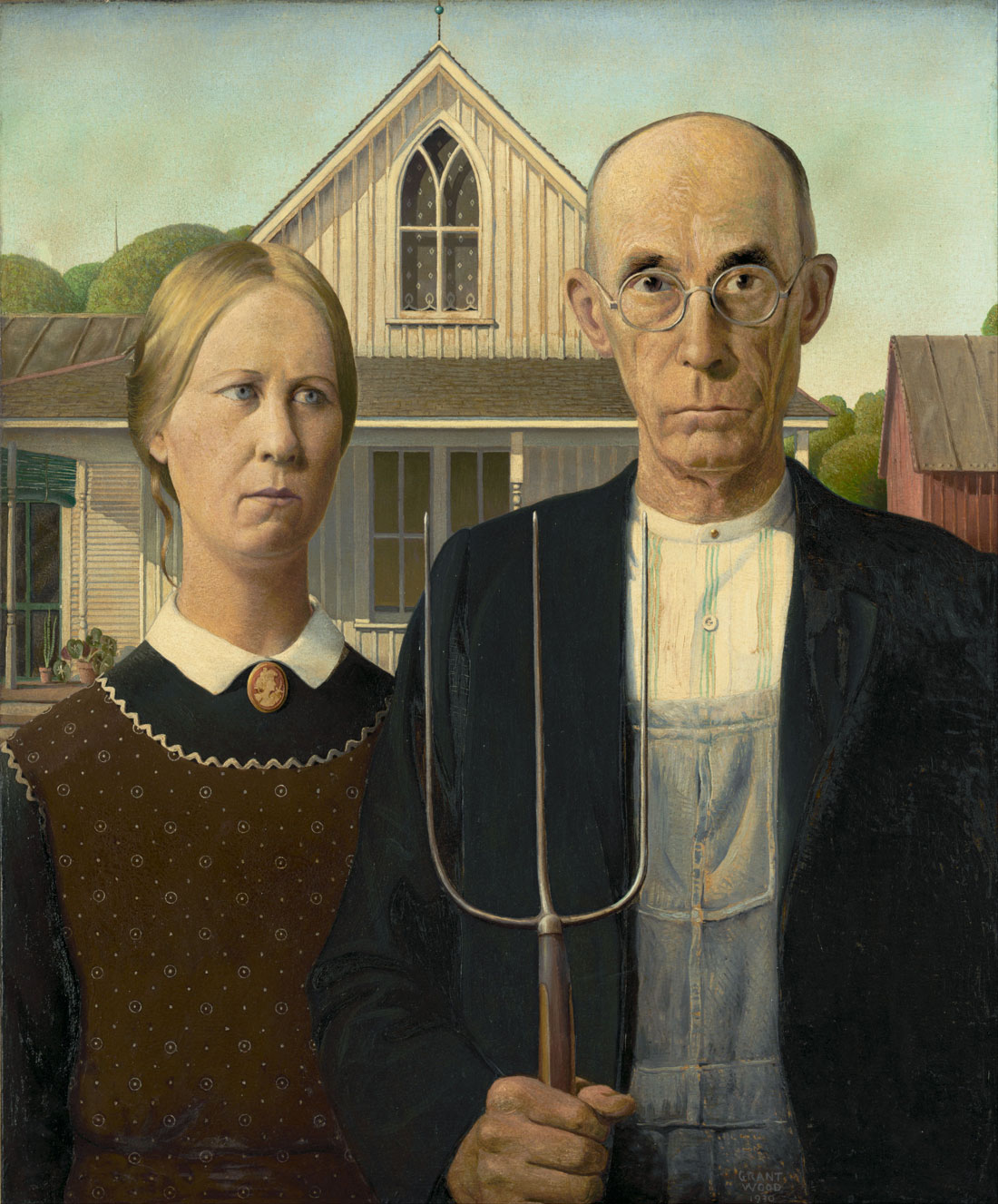

Carpenter Gothic houses and churches became common in North America and other places in the late 19th century. These structures applied Gothic elements such as pointed arches, steep gables, and towers to traditional American light-frame construction. A well-known example of Carpenter Gothic is a house in Eldon, Iowa, that artist Grant Wood used for the background of his painting American Gothic.

This painting is in the public domain.

Carpenter Gothic was popularized by house plan books of the mid-19th century which promoted the style for rural and small-town homes.

Melbourne and Sydney, Australia, saw the construction of large numbers of Gothic Revival buildings. including St John's College, St. Mary's Cathedral and government and university buildings.

Everywhere it spread, Gothic architecture was adapted to local sensibilities, creating styles such as Hindu-Gothic in India. In Beijing, China, the late 19th Century Church of the Saviour built on the orders of the Guangxu emperor was Gothic style but flanked by Chinese-style pavilions. Neo-Gothic style mingled with Neo-classic, Baroque and later Art Nouveau in Shanghai’s great business district, the Bund. In Guangzhou, China, the local cathedral copied the design of the Neo-Gothic Sainte Clotilde Church in Paris.

The Church of the Savior, or Northern Cathedral, in Beijing, China.

As Neo-Gothic began to give way to modern design in the early 20th century, some architects desparaged it as the “nineteenth century architectural tragedy”, but a number of influential books mid-century and the magnificent restoration of some of the best Neo-Gothic buildings helped revive an interest in Gothic architecture.

Over the past 15 years, furniture, clocks and lights inspired by Gothic churches, notably cathedral-style chairs with arched backrests, have appeared on the market along with new wallpaper and upholstery fabric reproductions of Gothic motifs.

After decades of modern architectural design, architects of some new churches in the United States are turning to traditional architectural styles. One example is a stunning new $14 million Catholic church called St. Clare of Assisi being built in Neo-Gothic style on Daniel Island, South Carolina. It will be the largest new church in the state.

In some cases, traditional architecture has been chosen because new churches are incorporating furniture and decorations from decommissioned or demolished churches that were designed in traditional styles with towers, spires, arches and rose windows, altar canopies, hammer beam ceilings and other elements of Gothic style. Some designs are incorporating stained glass windows salvaged from demolished churches.

Other examples are prominent Neo-Gothic buildings that recently have been or are being restored. St. Patrick’s Cathedral’s recent restoration left this jewel of New York sparkling. Another prominent example is the Neo-Gothic Salt Lake Temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a pioneer landmark in Salt Lake City that is being extensively restored and earthquake proofed. The six-spired temple was built by Mormon pioneers after the church’s leader, Brigham Young, sent architect Truman Angell to Europe to study European architecture during the height of the 19th century Neo-Gothic era. Angell’s Neo-Gothic sensibilities have influenced the styles of numerous other temples built by the church. The church also is restoring other pioneer-era temples in Utah that are a blend of Gothic and other 19th century revival styles, and has incorporated historic stained glass windows and features in new temples.

The neo-Gothic Salt Lake City Temple before its restoration began and, below, the building being restored.

As popular films and historical novels have highlighted aspects of Gothic style, medieval historical reenactments have become popular. A wave of tourism has drawn millions of tourists to historic churches in France, England and other European capitals and has sparked an interest in not only restoration, but in Gothic-style architecture on houses and other buildings. Much of the restoration of some well-known Gothic buildings has been paid for with donations from people who have visited the buildings as tourists and want to see them preserved.

Check out these related items

Gothic Architecture - Imagining Infinity

Gothic architecture has been called both magnificent and monstrous. We examine why.

Paris’s Oldest Church Restored

Paris' oldest church, Saint Germain des Prés, is emerging from layers of grime and soot as a meticulous restoration reveals its vibrant color.

The World Mourns Notre Dame

Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris, France's national cathedral, was badly damaged in a fire.

Resting Place of Kings

France's dazzling royal necropolis, the Basilica of Saint Denis, is also the birthplace of Gothic architecture.

How to Read Stained Glass Windows

Stained glass windows, one of the most durable types of art, have long imparted both powerful religious and secular messages.

Duke’s Beautiful Campus, Academic Excellence and Mixed Legacy

Duke University's Gothic architecture and academic excellence alongside its mixed historical legacy makes it a microcosm of the American South's historical dilemmas.