Charleston

“Many people, after spending a long weekend being stealthily seduced by this grand dame of the South, mistakenly think that they have gotten to know her: they believe (in error) that after a long stroll amongst the rustling palmettoes and gas lamps, a couple of sumptuous meals, and a tour or two, that they have discovered everything there is to know about this seemingly genteel, elegant city. But like any great seductress, Charleston presents a careful veneer of half-truths and outright fabrications, and it lets you, the intended conquest, fill in many of the blanks. Seduction, after all, is not true love, nor is it a gentle act. She whispers stories spun from sugar about pirates and patriots and rebels, about plantations and traditions and manners and yes, even ghosts; but the entire time she is guarded about the real story. Few tourists ever hear the truth, because at the dark heart of Charleston is a winding tale of violence, tragedy and, most of all, sin.”

— James Caskey, Charleston's Ghosts: Hauntings in the Holy City

Above, the peninsula upon which Charleston is located. This historic section of the city has been charmingly preserved, with a waterfront of 19th century mansions, historic churches and cobblestone streets.

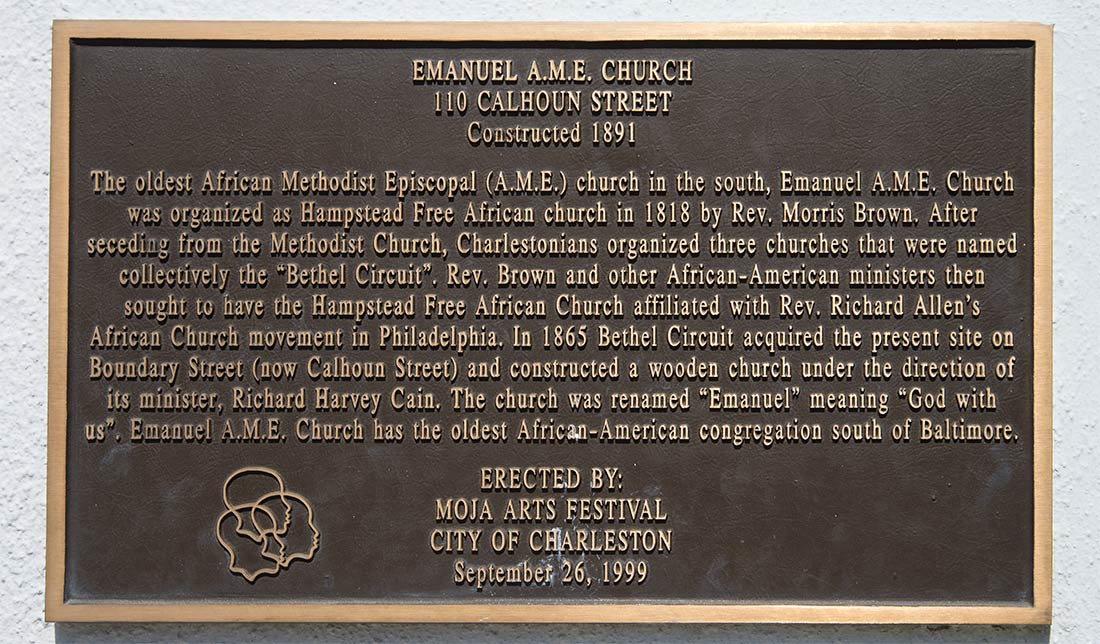

Emanuel A.M.E. Church in this historic area of Charleston was where a prominent African American state senator and pastor was shot and killed along with eight members of his flock on June 17.

The shooting in the South's oldest African American church was only the latest episode in Charleston's notorious history of racial violence. Some 40 percent of African Americans who were imported as slaves into the United States entered through Charleston's port. Slave labor made Charleston rich, built churches and mansions and motivated its white residents to lead the Confederate charge into the Civil War in 1861. The first battle of the war was fought at Fort Sumter (below) in Charleston Harbor, which became a Confederate stronghold until it was occupied by Union troops later in the war.

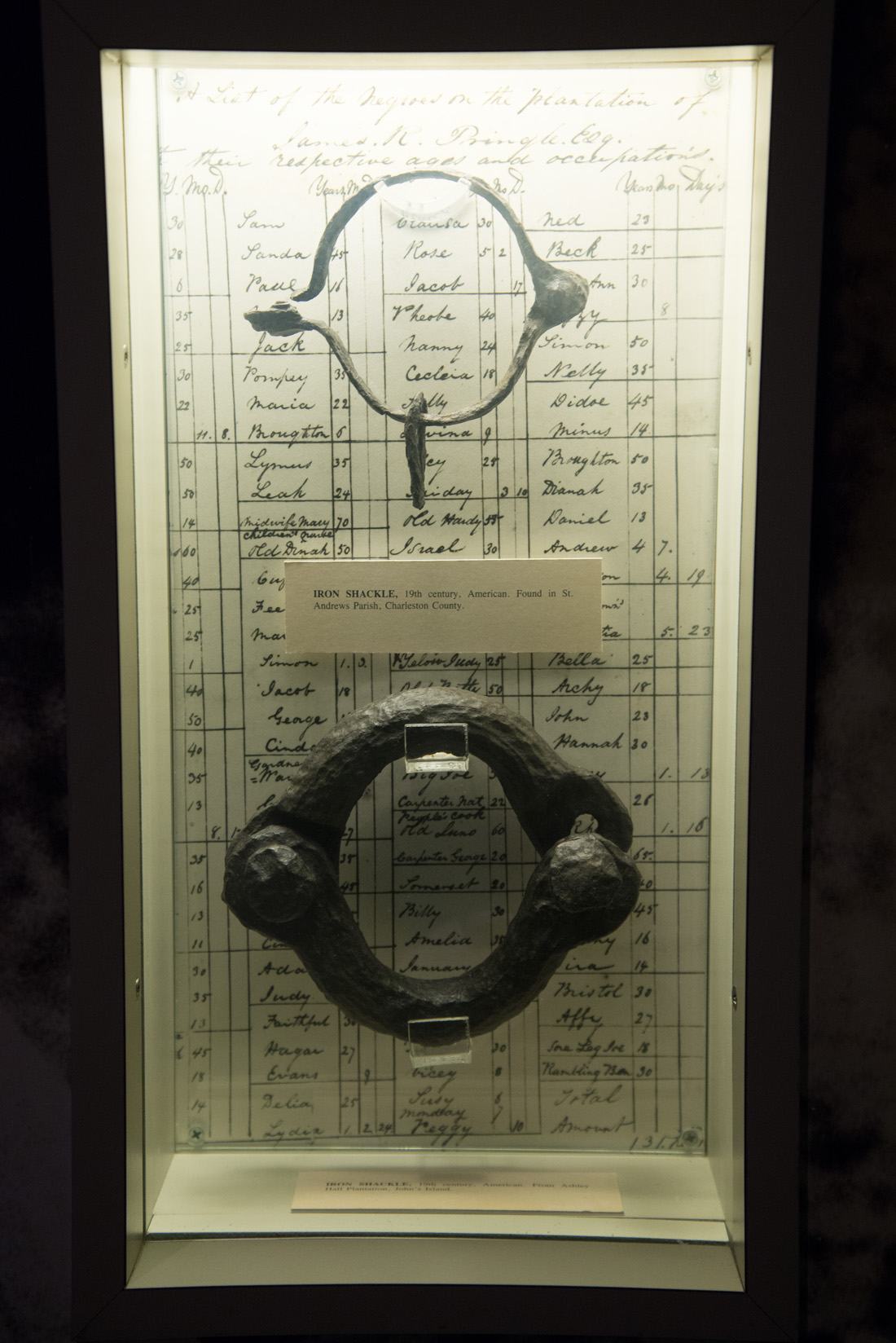

Unlike most southern cities, where the history of slavery is uneasily subsumed in high-rise modernity, Charleston today is fairly open about the heinous trade once plied by prominent citizens such as the DeWolfs. Slave shackles and metal tags that slaves were forced to wear are displayed at the city’s main museum. A former slave market has been converted into the Slave Mart Museum, which tells the horrifying story of human beings who were kidnapped and endured the terrifying Middle Passage to be sold at auction by traders who painted over their wounds to make them appear healthy. House museums owned by some slave traders are open for tours, their guides telling the story of the slaves along with their masters.

Founded in 1670 and named for English King Charles II, Charleston was America's key port in the trade that brought some 12 million enslaved Africans to America and the Caribbean.

It is one of American history’s most poignant paradoxes that Charleston is also known as one of the nation's most charming cities. Thanks to careful city preservation spurred by old fashioned Southern pride and the tourist industry, South Carolina’s oldest city is bursting with colonial charm even though it is among the fastest growing cities in the nation and a high-tech center.

Restored mansions with lush gardens line the waterfront, one of the nation's priciest strips of real estate. Some originally were built with slave labor and wealth generated by the slave trade.

Narrow cobblestone streets, re-enactors in pirate costumes, a Confederate monument around which African American and white children play together, colonial-era churches and doormen in elegant costumes characterize the picturesque historic district.

Thousands of slaves, many skilled rice farmers, were forced to work the tidewater rice plantations around Charleston. Many of their descendants still live in the Carolina low country, where they enrich it with African-influenced Gullah cuisine, the Gullah dialect, music traditions, weaving of Gullah sweetgrass baskets that have their roots in western African skills brought to America more than 200 years ago and religious traditions. Below, the old slave quarters of a plantation called Boone Hall.

Below, a tidewater plantation called Middleton Place. Weddings and joint family reunions of descendants of both slaves and masters who lived on the plantation are held there in addition to tourist activities. The tidewater marshes and gray Spanish moss hanging from the trees are Southern stereotypes.

A sweetgrass basket artisan sells her baskets in a Charleston market.

Nancy White demonstrates sweet grass basketmaking at Boone Hall plantation. The art of basketweaving was brought by slaves from Africa and adapted to the local sweetgrass plant. It is now a valued art form. Sweetgrass baskets are considered symbolic of long-lasting family ties, as the skill has been passed down from generation to generation for hundreds of years.

Women learn how to make sweetgrass baskets in a class at the local history museum.

Reenactor Doug Nesbit works as a cooper at Middleton Place.

Charleston is a kaleidoscope of cultures. The first settlers in 1670 were English who had previously settled in the English Caribbean colonies of Barbados and Bermuda. They and their slaves brought Caribbean traditions. Charleston was the southernmost English settlement in the American mainland for the next 60 years, until Georgia was established. The Spanish and French both contested the British claim to Charleston, and repeatedly tried to take it back, as did Native Americans. Pirates periodically raided. French, Scottish, Irish, Germans migrated to the developing port town. Wolof, Yoruba, Fulani, Igbo, Malinke, and other peoples of Africa’s Windward Coast were brought to Charleston against their will.

The colonial city was the fourth largest port in the colonies after Boston, New York and Philadelphia; the main hub of the Atlantic trade for the South and the wealthiest American city south of Philadelphia. Cherokees and Creek Indians traded in Charleston, sending tens of thousands of deer skins to Europe through the port to be made into gloves, book bindings and other leather goods.

In the post-Revolution area, Charleston prospered as cotton growing became South Carolina’s major export commodity. Slaves were the cotton growing industry’s primary labor force and the majority of the population. After the Civil War, the devastated city declined in importance, but has revived in the past quarter century as a high-tech center and tourist attraction.

Below, Rainbow Row, a row of colorful historic houses in Charleston. They were painted pastel colors beginning in the 1930s to invoke a Caribbean colonial color style.

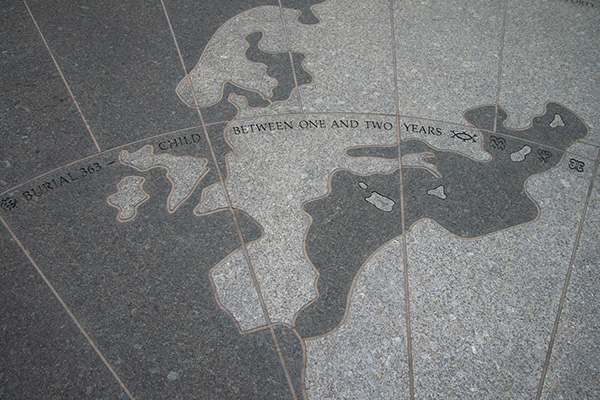

Slaves once were brought into holding pens on Sullivan's Island near Charleston before being sold in the city's markets. This monument is a memorial to them.

Check out these related items

The History of Race in America

The racial history of the United States belongs to us all, with the responsibility to resolve the accompanying outstanding problems.

Getting A Vaccine against Racism

A mother of non-white children compares her fears for her children because of COVID-19 and her fears for them because of racism.

The Racism of Confederate Statues

The racist past associated with the Confederacy and Confederate monuments has a complex history.

Wolf in Ship’s Clothing

The picturesque town of Bristol, Rhode Island, once was a slave port and home of the nation's leading slave traders, the DeWolfs.

The Land of Junipero Serra

Junipero Serra's "sainthood" is controversial, but the extent of his cultural impact on California is indisputable.

Memorial to Once-Forgotten People

A moving monument and burial ground in Manhattan comemorates enslaved people who once made up more than a third of New York City.