Illuminated Manuscripts

For thousands of years before the advent of the printing press in the 15th century, painting filled the role of illustration in cultures worldwide. A subset of it was illustrated manuscripts, which were produced in ancient Egypt, China, Japan, the Mideast and America and later in Europe. The word manuscript means “hand write.” These manuscripts encompass a wide variety of topics from religion, court life and history to literature, medicine, food and crafts. Along with art and architecture, they have transmitted the culture and knowledge of their times to us today.

Among them are illuminated manuscripts, which originally meant only manuscripts decorated with gold or silver but has come to refer to any decorated manuscript encompassing the European tradition and techniques of painting. These manuscripts are mostly Christian documents, but also include Islamic ones that use the same techniques.

Illuminated manuscripts with their elaborate initials, borders and miniature illustrations were painstakingly painted by hand, page by page. The earliest date back to 400 and were created in Italy or the Byzantine Empire by monastic scribes whose work preserved most of the existing literature of Greece and Rome. The majority of these texts were created for literate Christians. The illumination on them made them valuable and thus aided in their preservation.

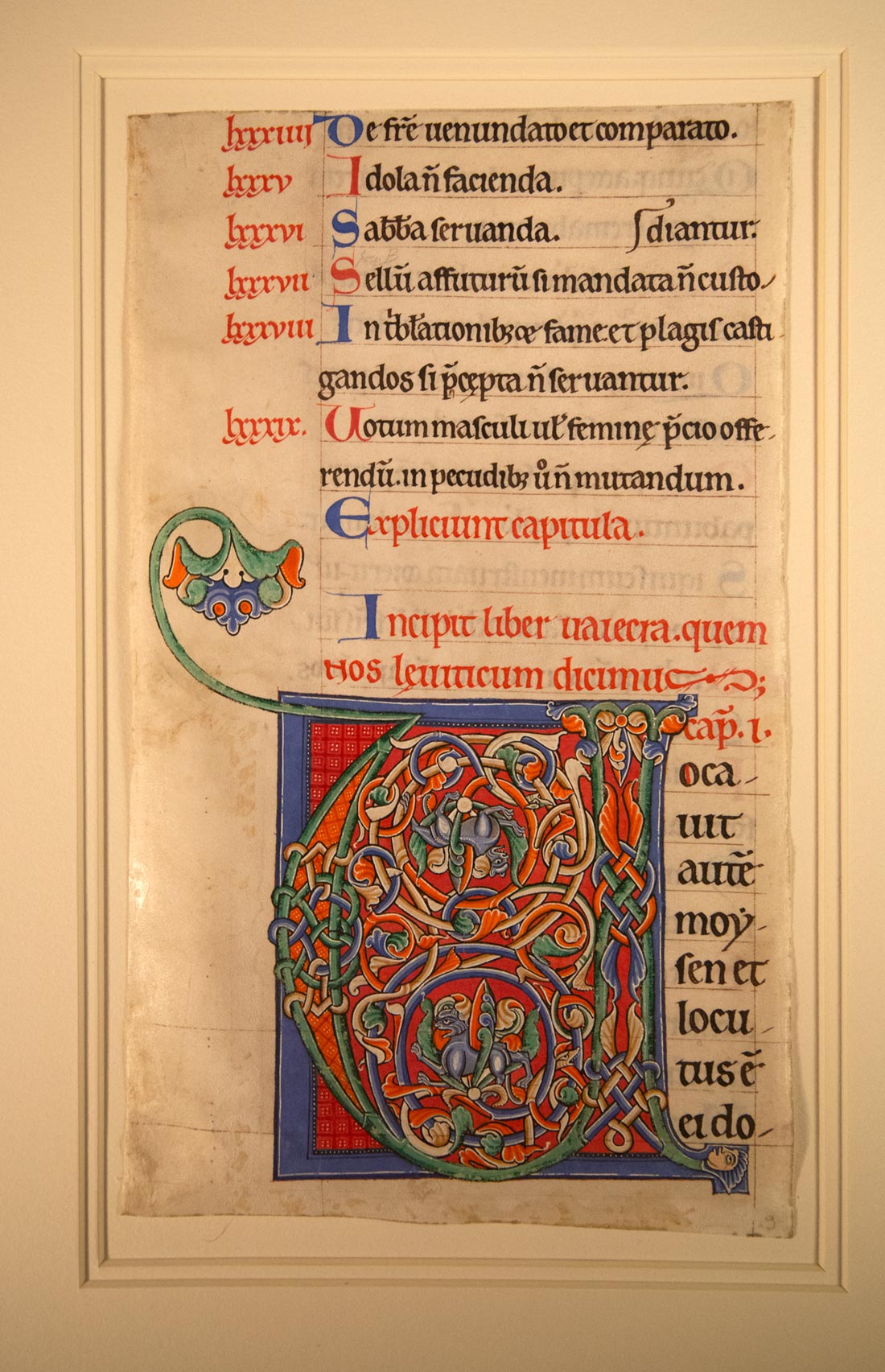

This is a 12th century initial from a Bible, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Most illuminated manuscripts are from the Middle Ages or the Renaissance and the majority are religious texts, although secular texts increased starting in the 13th century.

The vast majority that have survived were created on parchment. Parchment was made of animal skin. The highest quality of parchment, vellum, was made of calfskin. By the Middle Ages, codices or books had superseded scrolls as the common format. Paper had been invented in China in c. 105 CE and introduced into the Arab world by Chinese merchants by the 7th century. It was produced in Baghdad and Damascas and Muslim writers produced books of literature, poetry, science, astrology, and philosophy on paper, as well as copying western philosophers’ works onto paper. Muslim artisans elaborately illustrated the books as illuminated manuscripts. However, in Europe, use of paper was considered pagan and not accepted until the 11th century.

Instead, the monks who created illuminated manuscripts in monasteries made parchment by soaking animal hides in water, scraping them to remove the hair, stretching them on wooden frames to dry and bleaching them with lime. The vellum they used was durable and created a smooth, fine surface for writing.

From the 5th to the 13th century, only monasteries produced books. Every monastery was required to have a library and monks produced most of its books onsite. They made the vellum, copied and illustrated the books, and bound them in often elaborate bindings.

A monastery scriptorium was a large room furnished with wooden chairs and tables that angled up to hold the manuscript pages. The scriptorium director would distribute individual pages to the monks and supervise them. The books were meticulously planned out in advance and probably sketched on wax tablets.

The monks were expected to work in silence and only worked during the day, as lamps and candles were not used near the manuscripts for fear of fire. A monk would first cut a sheet of vellum down to the dimensions of the book, a practice that survives today in the rectangular shape of modern books that are longer than they are wide. The monk would then lightly rule the vellum for text and leave blank spaces for illustrations.

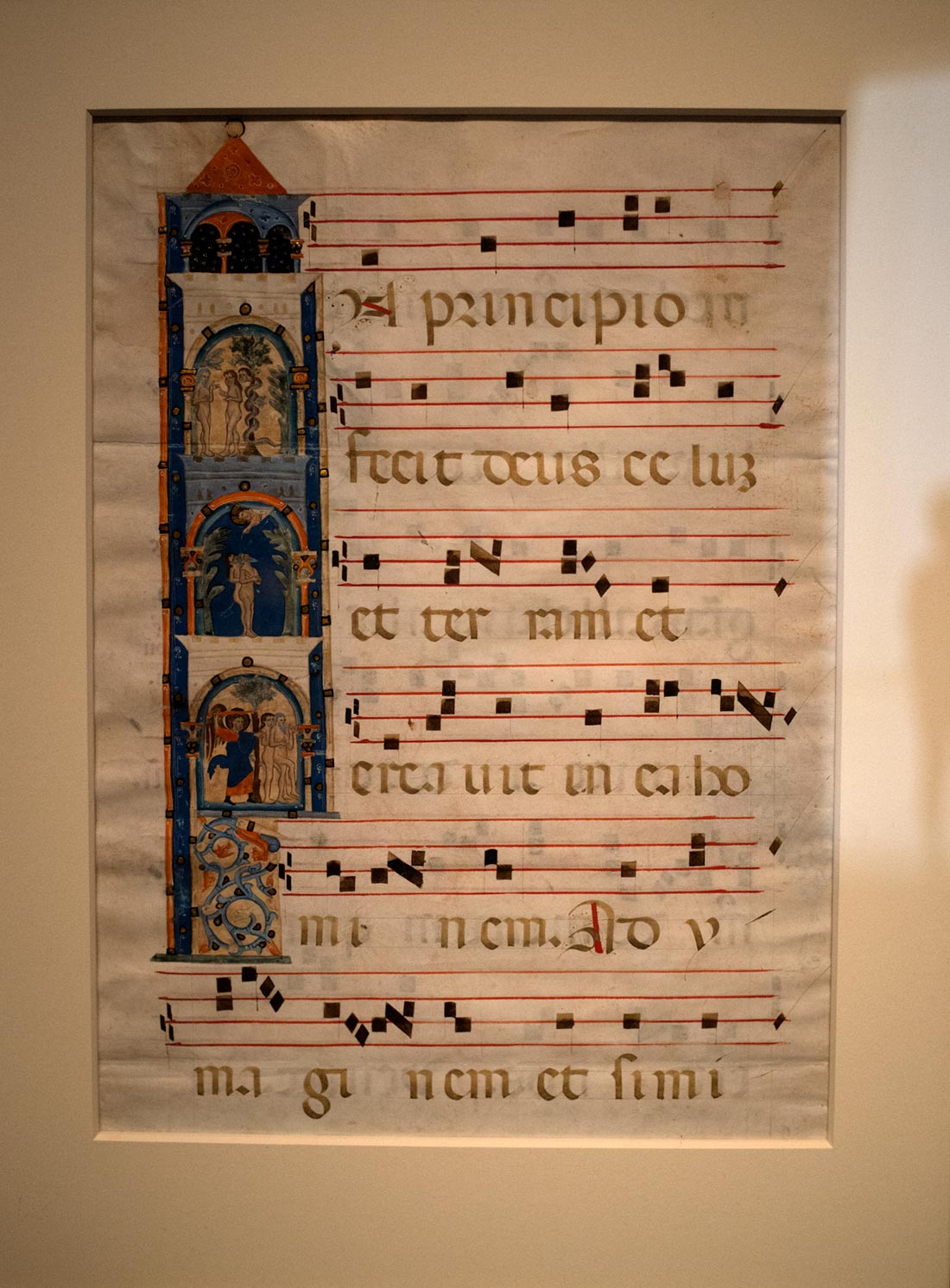

Rule lines are visible on this hand-written music from the San Juan Bautiste Mission in California, made sometime before the 18th century by a priest in the handmade manuscript tradition.

The monks wrote with quill pens and boiled tree bark, nuts and iron to make black ink. Other ink colors were made by grinding and boiling chemicals and plants. The text was written first, usually in black ink but sometimes in gold or another subject, between the ruled lines. It was then given to another monk to proofread for errors. A monk would then add titles in blue or red ink and then pass the page on to an illuminator to add gold, images and color illustrations in the blank spaces.

Most books had only a few decorated initials and flourishes because illumination was expensive, but display books such as Bibles to be placed on an altar were fully illustrated. Books used for study were often illustrated, but not in color.

The illuminator first created the outline of illustrations, then laid down gold leaf in areas where it was desired. After this, base colors were applied to areas that were to be colored, then darker tones to give the illustration depth and volume, and then details, lighter colors to highlight specific areas, and ink borders.

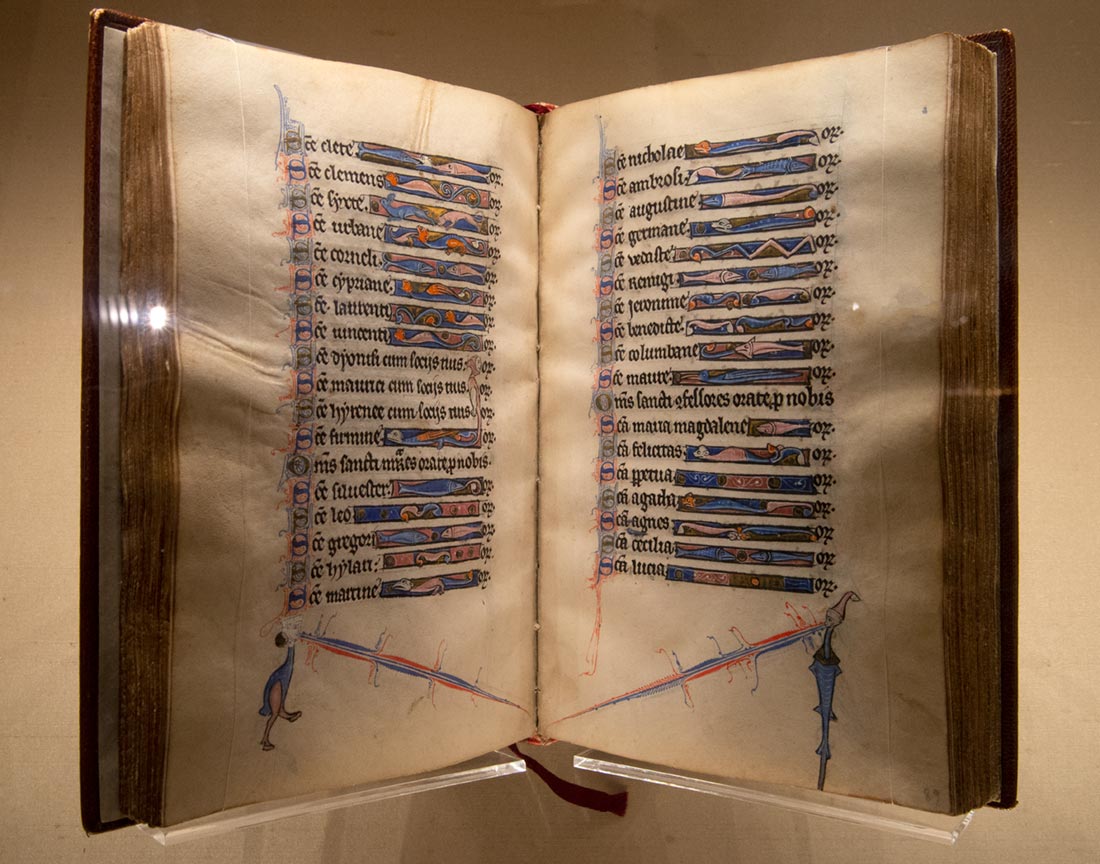

Later books had what were called drolleries - small drawings of wierd or grotesque creatures - in the elaborate borders.

The work was meticulous and tedious. The scriptorium was cold in winter and warm and stuffy in warm weather. The monks worked regardless of their health. They occasionally wrote brief complaints on pages such as “I don’t feel well today,” or “Just as the sailor yearns for port, the writer longs for the last line.”

Once all the pages were done, they were bound by hand and placed between covers, usually of embossed leather but sometimes elaborately carved wood with touches of carved ivory, precious metals and embedded jewels. Metal clasps held the parchment pages together and kept them from expanding. They were similar in style to the closed reliquary boxes popular in the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

This book in the Metropolitan Museum of Art is an example of the elaborate covers made for medieval manuscripts.

The making of a manuscript was often divided between four types of craftsman - parchment maker, scribe, illuminator, and bookbinder. Some books required the work of several craftsmen and assistants.

This Youtube video from the J. Paul Getty Museum shows the entire bookmaking process:

By the 7th century, book illustration and decoration had achieved a state of perfection, and the best illuminated manuscripts were produced after that. The best known is the Book of Kells, created ca. 800 by Scottish monks who probably took it to Ireland to protect it from a Viking raid that killed 68 monks in Scotland.

Many thousands of illuminated manuscripts still exist, and manuscripts are among the most common extant items from medieval times. For some periods, they are the only surviving examples of painting. They also are among the most affordable items for collectors, with many available for sale on ebay.com and other similar sites. Some collectors concentrate on a particular type of illuminated manuscripts such as Bibles or psalters and others collect illuminated manuscripts as part of a larger art collection with a particular theme, such as nativity art.

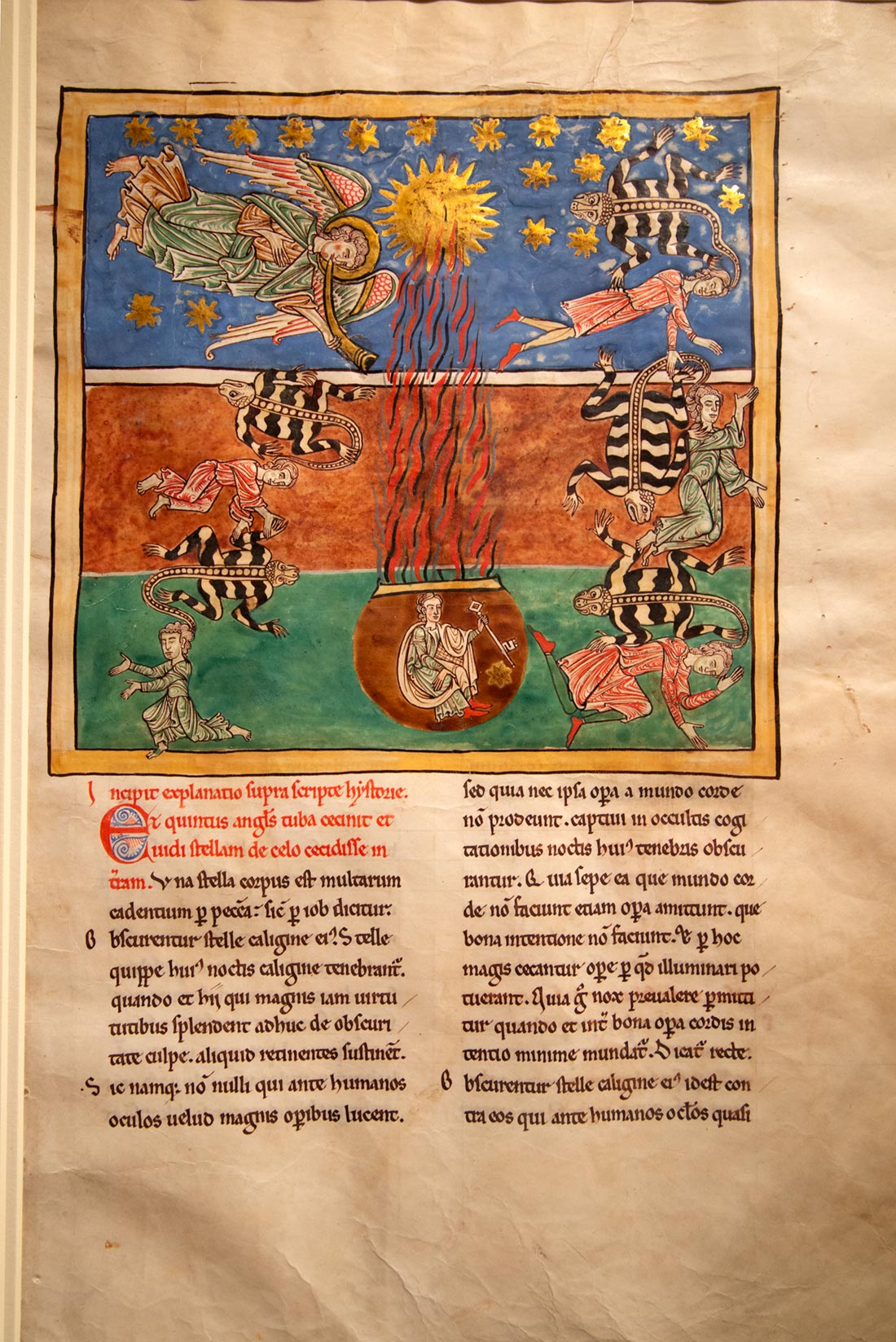

Among illuminated manuscripts are large, heavy complete Bibles, psalters, Gospel Books which contained all or part of the four Christian gospels, choir books and cards and posters depicting saints, knights, mythological figures, miracles and popular stories. Illuminated manuscripts are therefore a valuable window into the cultures in which they were created as well as the religious beliefs.

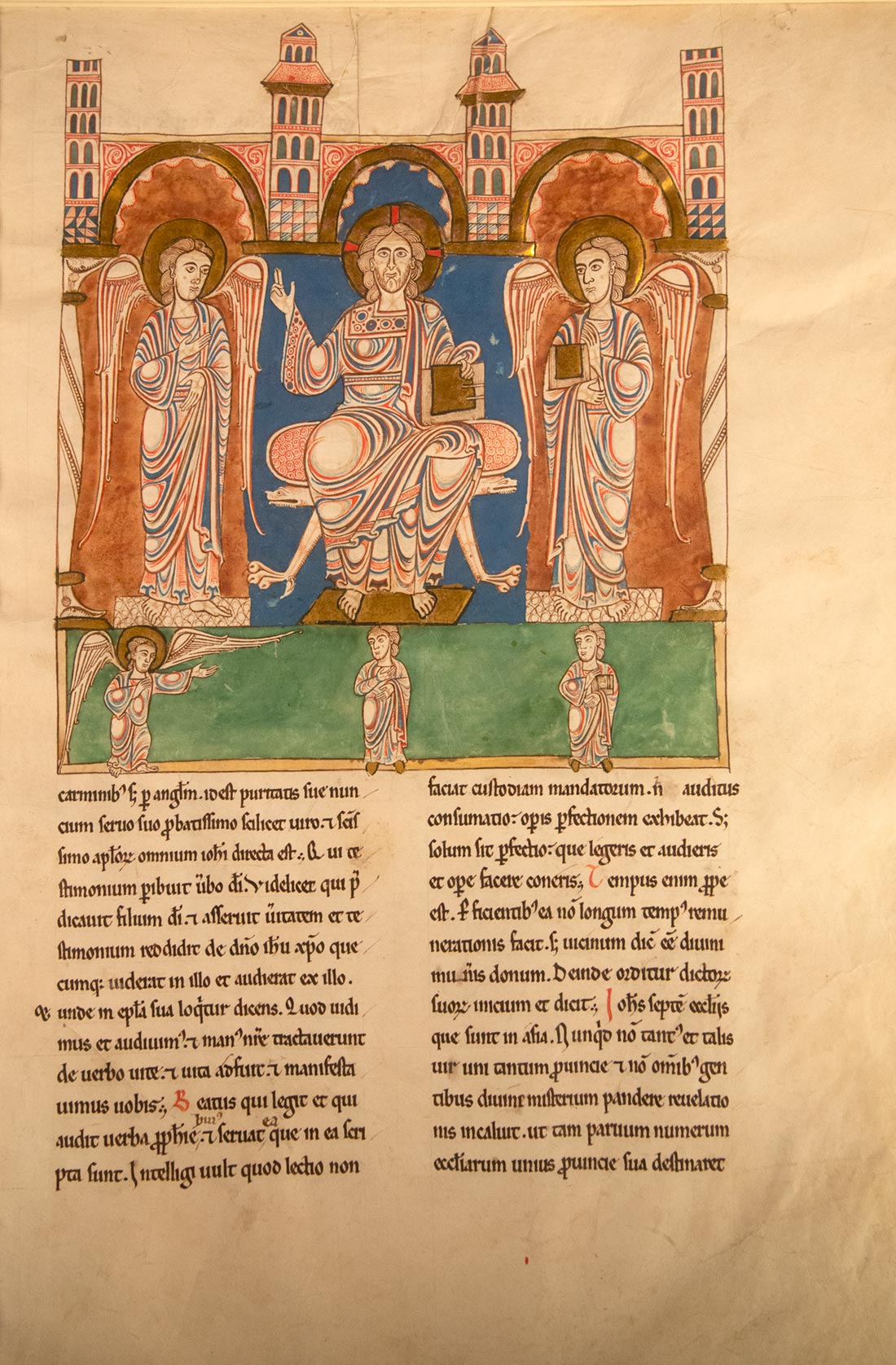

This manuscript page, painted about 1180, depicts St. John's vision of the end of the world. It is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection.

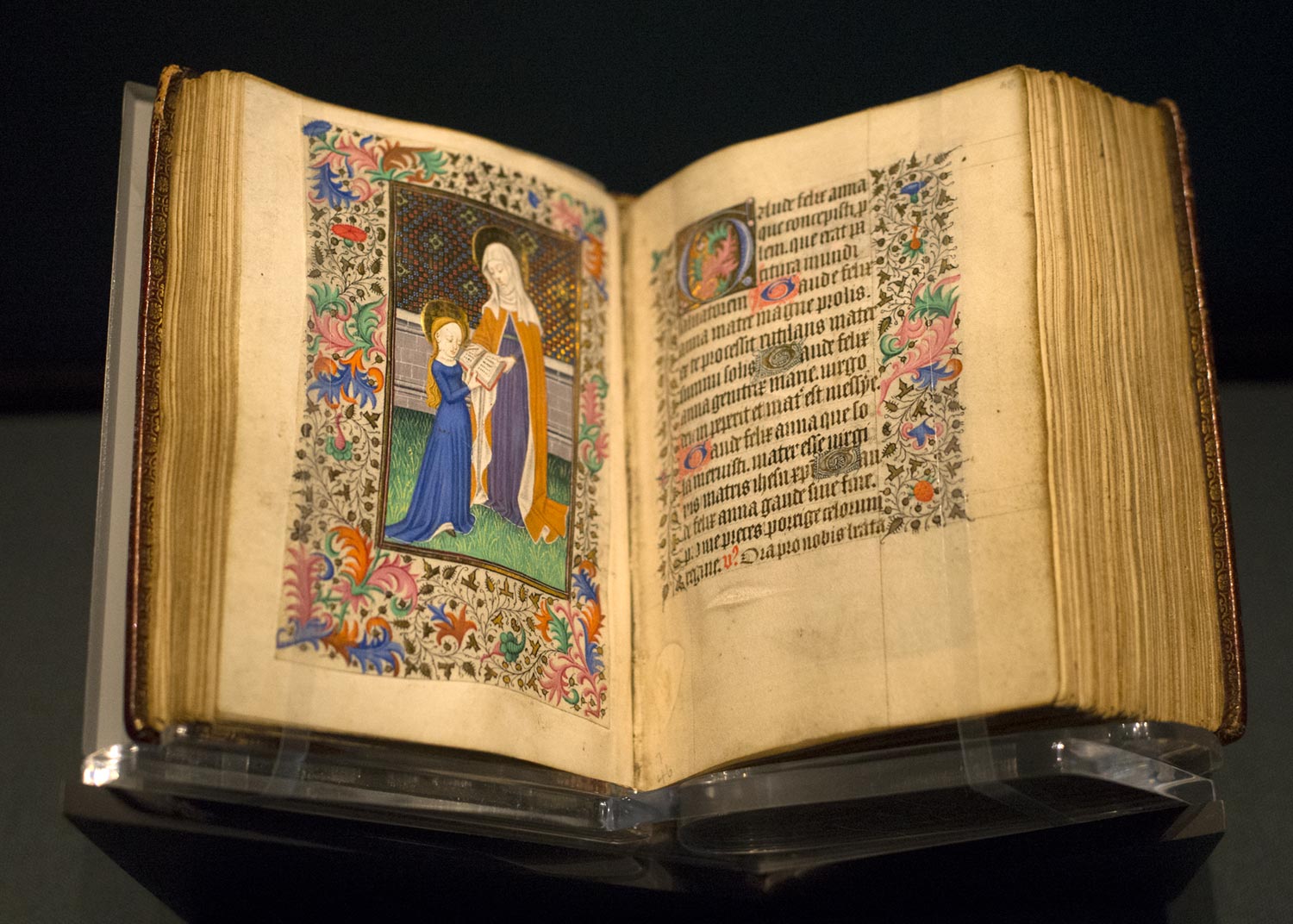

Among the most common illuminated manuscripts was the Book of Hours, a richly illustrated religious book for lay believers in Christianity.

This is a 12th century Book of Hours, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Different cultures and eras produced different styles of illuminated manuscripts.

Wealthy people collected books in personal libraries. Priests and monks used the books for liturgy, theology and music purposes in monasteries and churches, and took them to the Americas and other areas of the world.

As literacy increased after the 12th century and the society urbanized, books began to be produced by secular merchants and sold in book stalls and book stores. Centers of education moved from cathedral schools to universities in major cities. Stationers accepted book commissions from patrons, students or other lay people and then subcontracted the book making to specialized craftsmen and craftswomen. Secular books and books written in vernacular languages instead of Latin became popular. Women became involved as illuminators. Many illuminators were well known artists.

The introduction of printing led to the rapid decline of illuminated manuscripts, although they were produced for the very wealthy for a time.

Among my favorite museum collections of manuscript collections are those in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in the Medieval and Renaissance sections and those at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. These collections are fun to tour around Christmas time, as they include Nativity-themed manuscripts in the rich colors associated with Christmas. The manuscripts at the Met are displayed among Medieval art and sculptures, so it is possible to get a sense of the overall culture of which the manuscripts are a part.

Some manuscripts were miniature, enabling an itinerant monk to carry one around his neck as he traveled from place to place spreading Christianity. The role of illuminated manuscripts in spreading Christianity worldwide, including in the Americas, can be traced through still extant ones in old churches, missions and monasteries in many areas. The art in those books was used as a reference for decorating the interiors of colonial churches far from Europe.

Besides transporting the Bible and Christian theology, the manuscripts transmitted music not just to distant lands but forward in time so that we know what music was sung and performed in Medieval and Renaissance times.

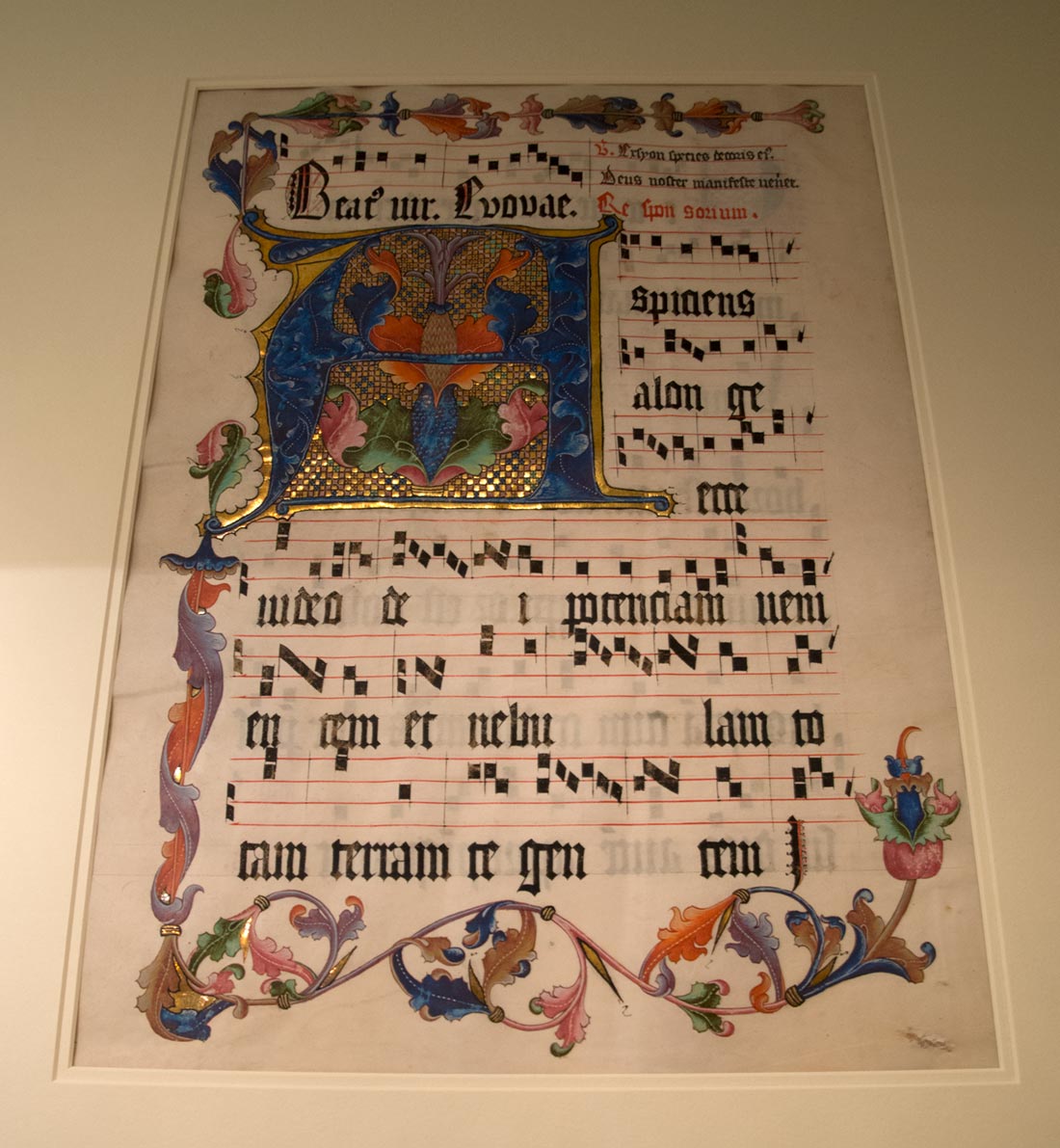

This manuscript of music is from the superb J. Paul Getty Museum collection.

This 15th century manuscript records a Christmas chant from a choir book. It is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This old hymn book in the tradition of illustrated manuscripts is from the San Juan Bautisto Mission in California.

Manuscript illustrations that depicted European religious architecture contributed to its transmission worldwide. This 12th century manuscript is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The manuscripts had a major role in defining the development of books. The word book comes from the Old English boc meaning a “written document” or “written sheet.” Decorated first initials in chapters and title sections written larger and in different colors for emphasis are still common in books today. Many fonts still in use today developed from script styles created or transmitted by monks in illuminated manuscripts. Experimentation with inks, media, styles and techniques advanced illustration in ways that still influence book design today.

Some styles such as Gothic were used in manuscript illumination as well as in paintings, sculpture, architecture and stained glass and still influence font styles. Art Deco and a number of other styles were heavily influenced by illuminated manuscripts.

Part of this process of cultural development occurred because printed books were at first considered cheap imitations of “real books". Printers tried to make their books look like hand-made ones by binding them in leather, adding gold gilt to the covers, and hiring illustrators to provide images. As the printed book became widely accepted, the skills of illumination were largely abandoned. However, illuminated manuscripts became even more valuable to collectors after they were no longer produced. The wealthy sought them out and built private collections that preserved the manuscripts.

Today, there has been a mini-revival of illuminated manuscript production as an extension of the popularity of calligraphy, which has attracted a wide following on Instagram, Pinterest and other social media sites. Medieval-themed movies, video games and television series as well as medieval and Renaissance reenactment events also have sparked an interest in illuminated manuscripts.

Check out these related items

Portraits of Mary

Mary, the mother of Christ, may be the most prominent visual icon in the world. We explore her history.

The World Mourns Notre Dame

Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris, France's national cathedral, was badly damaged in a fire.

Paris’s Oldest Church Restored

Paris' oldest church, Saint Germain des Prés, is emerging from layers of grime and soot as a meticulous restoration reveals its vibrant color.

Non-biblical Nativity Figures

Why are those figurines in large nativity scenes dressed in European dresses and broad-brimmed hats instead of Biblical costumes?

The Land of Junipero Serra

Junipero Serra's "sainthood" is controversial, but the extent of his cultural impact on California is indisputable.

Wise Men Came Bearing Gifts

We all want to give during the holiday season. Here are some tips on how to give wisely and well.