Reconstructing the Story of an Ancient Civilization

Photos by Forrest Anderson

An ancient people once occupied a vast area of today’s Utah, Colorado and New Mexico, leaving behind a unique form of apartment-style masonry architecture and a trail of pottery and other artifacts that is enabling archeologists to piece together their history despite the absence of a written record.

Interdisciplinary studies involving archaeologists, anthropologists, biologists, geologists, hydrologists and other researchers as well as satellite and lidar technology, computer data modeling and indigenous oral traditions have brought to light an ever-clearer picture of these people called the Ancestral Puebloans.

These people are best known for having built the United States’ largest archaeological site – the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde, Colorado. However, archaeologists now know that the entire Mesa Verde region, some 10,000 miles of today’s Utah, Colorado and New Mexico, was once the home of the Ancestral Puebloans. Some 18,000 sites which they occupied have been mapped in the vast arid region, with another 7,000 along the Rio Grande.

Mesa Verde.

The tale of these people and those who have studied them for almost 150 years is a complex one of migration, climate change, culture, violence and mystery. It’s hard to know where to begin because as knowledge of the Ancestral Puebloans has grown, their story has pushed back further in time.

Scientists say Mesa Verde was inhabited seasonally by nomads as early as around 7500 BC and later peoples built semi-permanent rock homes in the mesa. A group of basket makers emerged from these peoples by 1000 BC, from which the Ancestral Puebloan civilization sprang. Recent research indicates that hunter-gatherer groups lived on the Colorado Plateau and experimented with agriculture as early as 800 B.C. They intermingled with immigrant farmers from southern Arizona by 400 B.C. and became corn farmers in the first few centuries A.D. Initially, they settled and farmed in low-lying areas near permanent streams. They lived in small communities within walking distance of their fields. High quality land was plentiful. As the population grew, they began to locate their homes on or adjacent to their own land.

The Ancestral Puebloans were one of four major prehistoric traditions in the American Southwest, the others being Mogollon, Hohokam, and Patayan. The Ancestral Puebloans occupied the northeast, their home centering on the Colorado Plateau and extending from central New Mexico in the east to southern Nevada in the west. The southern edge of their territory was the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers in Arizona and the Rio Puerco and Rio Grande in New Mexico. However, the borders of the lands were not well defined and evidence of them has been found in the Great Plains.

Their population increased rapidly after 600 in the Mesa Verde area and there were at least 5,000 people there by 800. They grew corn, beans and squash, which still remain the basis of Southwest cuisine. They built pit houses with hearths, fire holes and storage areas that were entered by ladders. Because they were partly underground, these homes were cool in summer and warm in winter. They also built large round structures that were partly underground and that are called today kivas. Modern Puebloans still use kivas for ceremonies. Some kivas were more than 1,000 square feet. They are believed to have been public gathering places for socializing, ceremonies and discussion of community issues.

In about 700, the Ancestral Puebloans also began to build surface dwellings with flat roofs that were joined in long rows. Houses with more than one story and round towers appeared. They eventually built two-to-three-story pueblos with 50 or more rooms. Yellow Jacket Pueblo, a ruin that also is in the Mesa Verde area, had 600-1,200 rooms and a population of 700.

The Ancestral Puebloans were such proficient hunters with bows and arrows that they eventually overhunted game and had to resort to domesticating and eating turkey.

They produced finely woven baskets and pottery with technology that originated in Mexico. Studies of the pottery support the conclusion that new varieties of corn suited to growing in the cold arid climate of the Colorado Plateau, the addition of beans to their diet and the development of cooking pottery provided them with a purely agricultural diet that supported significant population growth. However, there also would have had to have been substantial migration into the area because the Mesa Verde population more than doubled between 700 and 850 and the size of individual communities grew. From 700-1130, a ten-fold increase in population was the result of consistent rainfall that supported agriculture and increased human fertility plus migration into the area and agricultural and technological innovations. As many as 100,000 people may have occupied the Four Corners region at the peak of the population.

Between 850 and 900, people temporarily left in large numbers, heading south to areas such as Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, possibly because cooler temperatures that made farming corn more difficult. However, they returned after 930 and built multi-story “great houses” on high ground as places for ceremonies, meetings and central storage and distribution of food and trade goods.

Obsidian, Chaco-style pottery, macaw feather sashes, and copper bells found at archaeological sites support the conclusion that the Ancestral Puebloans were part of a vast trade and cultural network that linked hundreds of communities and reached into Mexico.

People left again during a period of drought and violence in the 12th century, but the population revived. Between 1150 and 1200, the people began to build houses and entire villages in caverns in the walls of deep canyons that had been formed by erosion.

A canyon where cliff dwellings were built.

Today there are some 600 of these cliff dwellings in Mesa Verde National Park. Some had more than 200 rooms and 100-200 people living in them, and some just one or two rooms. Some people also continued to live in multi-family structures that were not cliff dwellings.

The Cliff Palace, the most well known of the cliff dwellings, has 150 rooms, nearly two dozen kivas, and decorations such as stamped handprints above doorways and animal figures painted on walls. It has both round and square towers.

Analyses of settlement indicates that the largest, longest-lived and most prosperous communities were established earlier on more productive land, so levels of inequality developed. It is possible that internal conflict over resources or pressure from other intruders prompted the Ancestral Puebloans to begin to build apartment-like complexes of stone, adobe and other local material on the sides of canyon walls and by the 12th century, high up in caverns in cliffs. This trend of congregating growing populations in close defensible quarters is best known from the extant cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde, but it was region-wide.

The cliff dwellings are the product of a society that made musical instruments, turquoise jewelry, distinctive black-on-white decorated pottery and master stone masonry. Some of the design details in the cliff dwellings appear to have been imported from Mexico. They faced their houses south, with plaza areas surrounded by houses that were several stories high and had terraced flat roofs. In some areas, they built with wood transported substantial distances.

When I first saw the Mesa Verde black-on-white-or-gray pottery, which is distinct to the area, I was struck by its resemblance of some of the designs on Neolithic pottery from China. Swirls interspersed by stripes also are seen on the Chinese pottery. I have not been able to find documentation of a cultural connection, so that's a mystery for another day.

The Ancestral Puebloans clustered ceremonial structures around kivas, circular rooms used for living and ceremonial purposes.

They cut ramps and stairways into cliffs that connected to roadways leading to springs, lakes, mountaintops and other communities.

The building of the cliff dwellings represented the importation into caves of the already existing apartment-like buildings. Because the buildings were limited to the size of caves, they shrank in size in that environment. In some canyons, almost every cave was used, with far more small cliff dwellings than large ones. Many in deep crevices can be seen only from certain places when light conditions are right. Some of the cliff dwellings are so small – 3 feet high and four feet wide – that it is unknown how they were used.

Cliff dwellings can be seen across the canyons.

Cliff dwellings can be seen across the canyons.

The cliff dwellings provided a type of passive solar shelter. They were cool in the summer when the sun was high and couldn’t get into the caves, and warm in the winter when the sun was low and shone into them. It also is clear that the cliff dwellings were a type of easily defendable fort, indicating that the people were trying to defend themselves from raiders or other hostile peoples. They had retractable ladders, ropes or toe holds by which people climbed into and out of them.

Even today, tourists enter the ones open to the public through ladders and narrow passages in the rock.

Toeholds in the rock that were used to enter the cliff dwellings still can be seen.

A tourist going through a narrow passage to enter a cliff dwelling. Such passageways made the cliff dwellings easily defensible.

Archaeologists know that the average lifespan of the cliff dwellers was just 32-34 years, and they ranged in height from 5 feet to five feet four inches. About half of their children died before age five. They farmed on terraces, made their homes of sandstone, mortar and wooden beams. In one location, not in a cliff but in the open, they built a roofless structure that is believed to have been used for ceremonial purposes.

Tools for grinding corn, their main food source.

A 300-year drought spread across America after around 1130, causing the collapse of some other indigenous civilizations. The Ancestral Puebloans decreased trade and interaction with more distant communities, developed irrigation techniques and abandoned locations that had arid conditions. They left the Mesa Verde regions entirely and resettled elsewhere in about 1280, during a local drought period from 1276 to 1299. It is unknown whether drought was the main reason for their migration. Some places appeared to have been abandoned precipitiously. Some ceremonial structures were deliberately dismantled, sealed or burned and some had fires set in them. Homes were abandoned with pots left on earthen floors and mugs hanging from pegs on the walls.

Computer simulations of the enormous amount of data available on Ancestral Puebloan sites, run hundreds of times with tweaks in the parameters, have revealed that people moved out of some canyons and into more agriculturally productive areas at about the same time that wild deer populations declined from over hunting. At the same time, the number of turkey bones in refuse heaps increased. As corn-fed domestic turkeys surpassed deer as the main source of protein, the food supply became dependent on a single crop. If there wasn’t enough rain to grow corn, there could be food shortages. Hydrologists, however, have found that groundwater seeps and springs in the region probably didn't dry up even in the most arid years and the soil’s ability to hold moisture would have enabled it to produce enough food to support the population, so it is unlikely that people would have been driven away from Mesa Verde by drought alone. Moreover, most of the people had left by 1276 when the local drought took hold.

There is evidence of warfare at some sites. A 1997 excavation at Cowboy Wash near Dolores, Colorado, found remains of at least 24 human skeletons with evidence of violence, dismemberment and cannibalism. The community appeared to have been abandoned during the same time. Other excavations also have produced unburied and dismembered bodies. However, this evidence is debated by scholars and members of modern Native American tribes, with a number of alternative explanations. By the time archeaologists began excavating the cliff dwellings in the early 20th century, looters had stripped them of artifacts that could have helped determine why the Ancestral Puebloans left. One early looter, Charles Mason, described entering one cliff dwelling that had skeletal remains scattered about and evidence of a violent conflict:

"There is scarcely room to doubt that the place withstood an extended siege. In the entire building only two timbers were found by us. All of the joists on which floors and roofs were laid had been wrenched out. These timbers had been built into the walls and are difficult to remove, even the little willows on which the mud roof and upper floors were laid were carefully taken out. No plausible reasons for this has been advanced except that it was used for fuel.

“Another strange circumstance is that so many of their valuable possessions were left in the rooms and covered with the clay of which the roofs and upper floors were made.... It would seem that the intention was to conceal their valuables so that their enemies might not secure them.... There were many human bones scattered about, as though several people had been killed and left unburied....

“It seems to me there can be no doubt that the cliff dwellers were exterminated by their more savage and warlike neighbors ...., though in some cases migrations may have become necessary as a result of drouth or pressure from outside tribes.”

There is no academic consensus exactly where the people of Mesa Verde went, but they are believed to have migrated mostly south to locations with dependable water sources and merged into other Puebloan peoples whose descendants still live in Arizona and New Mexico. Some Puebloan oral traditions support this notion.

Modern Puebloan cultures contain elements of not just Ancestral Puebloan culture, but that of the Mogollons and Hohokams. Today, 100 pueblos are still inhabited, and Puebloans speak four distinct language families, with English as their lingua franca because the four languages differ completely in vocabulary, grammar and most other aspects. The pueblos are bound together by their mutual cultivation of varieties of corn, tight-knit clan communities and tradition. The exact numbers of Puebloans today are unknown. Some 35,000 Puebloans live in New Mexico and Arizona but there is a much larger group of people who share Puebloan, Hispanic, white and other ancestry.

The Pueblo style of architecture is still enormously popular across the Southwest. The Spanish introduced modular adobe blocks, but the stacked rectangular styles are native American.

Migrations usually are traced using architectural styles or pottery, but both the style of the Mesa Verde buildings and their pottery are unique. There is no evidence that the Mesa Verde peoples took them with them.

Dr. Scott Ortman, a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder has drawn on the oral histories of the Tewa Puebloans on the Tewa Basin north of Santa Fe, New Mexico, 250 miles south of Mesa Verde, to explain the Mesa Verde inhabitants' southern migration. Tewa stories chronicle a “12-step” journey by their ancestors south to the Tewa Basin. Ortman, who studied the Tewa language and culture, hypothesized that this journey was that of the Mesa Verde Puebloans. He also found similarities between words in modern Tewa, such as the word for a church roof which translates as “basket made of timber” and the Mesa Verde’s woven timber construction for kivas.

The construction of "woven" wood roofs in Mesa Verde kivas can be seen in this restored one.

People descended into a kiva using a ladder in a central hole in the roof.

Tewa pottery doesn’t incorporate weaving techniques, but Tewa words describing pottery derive from older words for woven objects. Mesa Verde pottery did incorporate weaving techniques. These connections led Ortman to suggest that the Tewa language originated in Mesa Verde, which the Tewa called Tewayoge or “the big Tewa place.”

Ortman studied measurements by earlier researchers of ancestral Puebloan human remains across the Southwest and found that those from the Tewa were biologically the same as those of ancient remains from Mesa Verde.

Turkeys, which still can be seen at Mesa Verde and which the ancient people there raised for their feathers and food, were another link. The DNA of turkey bones in the Tewa region changed in about 1300. The new DNA matched that of turkey bone DNA found at Mesa Verde, indicating that ancestral Puebloans of Mesa Verde took their flocks of turkeys with them when migrating to the Tewa Basin.

The Tewa Basin also had an increase in its population at about the same time that Mesa Verde’s population dropped off. Some experts believe that a few people from Mesa Verde integrated with the Tewa, but that most of them went instead to Pueblo tribes where the Keres language is spoken.

In accounts recorded by anthropologists nearly a century ago, Tewa people cited names for places in southwest Colorado to which they had never been. One story matched an archeological site named Yucca House, one of the most unique sites in the Mesa Verde region. Yucca House had 600 rooms and kivas with corn and squash growing around them. There was a communal plaza similar to the plaza at Ohkay Owingeh where Tewa dancers perform on local feast days. Pottery and tree-ring dating indicate that Yucca House was one of the last places occupied by Ancestral Puebloans before they left the region. Ortman says Yucca House looks like the people of the Mesa Verde area were trying out a new way of community living that looks like a prototype of the typical Tewa village.

He thinks that as Mesa Verde’s way of life unraveled, its inhabitants headed for the Rio Grande and may have abandoned their art and architecture from Mesa Verde’s final years in favor of something that more closely resembled Yucca House.

At Tewa Basin, incidents of violent death decreased and the people prospered during the same time that the Mesa Verde people would have migrated, creating stable communities that have survived for more than 900 years. The Tewa people believe that the Mesa Verde cliff dwellings are still inhabited by the souls of their ancestors.

The huge amount of data on Ancestral Puebloan sites makes it difficult to assess how the population grew and declined over time and space, but computer data-crunching and modeling is revealing new details. The evidence indicates that the number of people who left Mesa Verde in the 1200s was roughly the same as the number who moved into the Tewa Basin shortly thereafter.

The abandoned cliff dwellings were known to other tribes such as the Utes and Navajos who came into the area but did not reoccupy them. Spanish explorers who entered the area after the 1600s enslaved Puebloan peoples elsewhere but apparently didn’t discover the cliff dwellings.

Navajos in the area called the people who had dwelt in the cliff dwellings Anasazi, which means “the ancient ones: or “ancestors of our enemies.” Modern Puebloans dislike the name, favoring Ancestral Puebloans.

The Ute, who were mobile raiders and traders, controlled the area by 1750. They and Navajos were guides for early U.S. explorers in the area.

In 1874, photographer W. H. Jackson came into the region making a photographic survey for the government. He heard of ancient ruins in the region and hired a miner to guide him to them. Jackson made the first photographs of the cliff dwellings. Cliff Palace was found by a nearby rancher, B.K. Wetherill and his family members in December 1888 after a Ute told them about a large cliff dwelling. They made their way down to it and explored it, finding a stone ax with a handle and human skeletons.

Wetherill and his family collected artifacts from more than 182 cliff dwellings, documented them and sold them to museums and other collectors. These items are held in museums throughout the world. Their collecting drew others to the area who looted many of the cliff dwellings without regard to their historical context. Some blew up parts of the dwellings with dynamite in search of artifacts.

In 1891, a Swedish archaeologist excavated Spruce Tree House and other ruins and took some 600 artifacts to Sweden. Negative publicity in the United States around his work eventually led to the formation of Mesa Verde National Park to protect the cliff dwellings. Efforts to return the Mesa Verde artifacts from a museum in Finland began in 2015, and Finland agreed to do so. They ultimately were to be reburied near the sites where they were unearthed.

The ruins that were open to the public were excavated and repaired to their current condition after 1906.

Today, the cliff dwellings are threatened by climate change that has caused more rapid freeze-thaw cycles in which water seeps deep into the stone, freezes and then expands. After the ice melts, water sinks deeper into the rock and the cycle occurs again, weakening the masonry on the dwellings.

Wildfires are another threat to the park. Mesa Verde has lost about half of its forest cover since 1906, when it was founded, with fires burning 24,000 acres from 2000 to 2003. However, in recent years, fire detection has improved so that firefighters can suppress fires quickly and the weather has not been quite as dry. Fire has scarred some of the cliff dwellings’ walls. It also covers the soil with a hydrophobic layer that keeps water from soaking into it. Instead, it pours over the land, causes flash flooding that can damage ancient artifacts. One farming terrace used by Ancestral Puebloans has red splotches from firefighting foam used to fight fires. Ancient ruins subjected to high heat from fires have had stones pop off. At the same time, archaeologists have discovered hundreds of ancient sites in areas where fire cleared forests. The National Park Service has worked on a canyon-by-canyon inventory to figure out how many of the cliff dwelling exist and how they behave under different climate scenarios.

The mean average air temperatures in southwest Colorado have increased by two degrees over the past three decades, causing bark beetles that thrive in warmer temperatures to ravage forests. The temperatures are expected to rise another two-five degrees in the next 15 years, which will mean a twelve-fold increase in risk from wildfires as well as longer summers.

National Park Service rangers conduct guided tours of Cliff Palace and other cliff dwellings between May and September. Self-guided tours of smaller sites are available as well. Mesa Verde is a fascinating place to add to your travel bucket list after the pandemic subsides.

Check out these related items

The River That Keeps on Giving

The mammoth Colorado River is the lifeblood of the southwest United States, supplying water and power for cities and agriculture.

What does it mean to be Hispanic?

What does it mean to be Latino or Hispanic in the United States? This blog explores the ambiguous origins of these two terms.

The Land of Junipero Serra

Junipero Serra's "sainthood" is controversial, but the extent of his cultural impact on California is indisputable.

Mountain Men and the Fur Trade

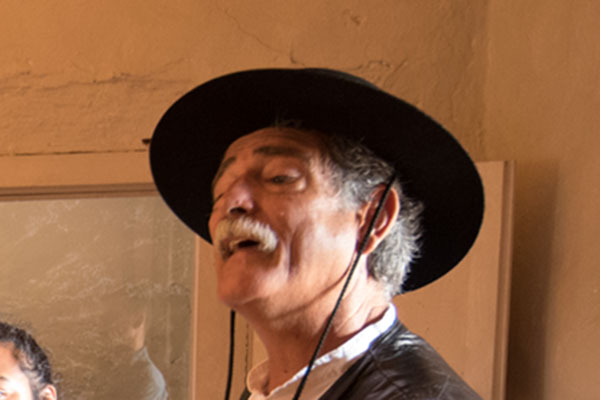

The colorful annual mountain men rendezvous at Fort Bridger, Wyoming, commemorates the 19th century global fur trade.

The History of Race in America

The racial history of the United States belongs to us all, with the responsibility to resolve the accompanying outstanding problems.

Traces of an Ancient Superpower

Traces of an ancient Chinese superpower remain far away in Japan, the eastern end of the Silk Road.