The Real Cost of COVID

Photos by Forrest Anderson

As the nation voted last week, exit polls indicated that many people voted along partisan lines depending on whether they thought controlling the pandemic or opening the economy was more important.

This raises the question: Are controlling the pandemic and economic recovery competing goals? What do the data and the experts – epidemiologists and economists- say? I decided to dive deep. Here’s what I found out:

The Virus

The particular nature of COVID-19 has contributed greatly to its overwhelming spread because, unlike SARS and other contagious diseases, it can be passed on by people who exhibit no symptoms and don’t know they have it. It packs a double whammy because people who have it are most contagious one to three days before they start to show symptoms. This has made tracking and fighting the virus’s spread unusually difficult and rendered traditional virus tracking and quelling measures far less effective. The usual lag of two to five days in getting test results has exacerbated this problem. It is the difficulty of detecting the virus quickly that has made wearing masks and social distancing to prevent transmission so crucial.

The virus also is more lethal, both alone and in its ability to worsen the symptoms of other leading diseases such as diabetes, heart disease and respiratory problems, than other common infectious diseases such as the flu.

The Culture

These characteristics of the virus have interacted with the extremely mobile, open and social nature of modern American and European culture. It is hard to imagine cultural environments that would be more conducive to the spread of this virus than the United States and Europe. Both of these regions have efficient and far flung transportation and business networks, as well as associated cultural habits of traveling, eating out, hugging, handshakes, shopping, endless social rituals and overlapping of interconnected social groups.

American culture in particular is one of highways and airways, built expressly for fast, frictionless transportation of people and goods. The virus has spread easily along the same routes that we all do business and socialize on. It has proved to be extremely problematic to shut down or introduce enough friction into the system in the form of quarantines, social distancing and mask wearing to quell the virus, mainly because such measures work against the entire premise and structure of our economic and social model. The result of our frustration has been political polarization in which opening the economy and pandemic control are seen as competing goals.

Because of this polarization, one would think that economists and epidemiologists would be on opposite sides of the issue. However, that’s by and large not the case. Both say the polarization is producing a false tension when we actually need to implement overlapping strategies that control the virus and revive and protect the economy in concert. Scientists have known for well over a century that improvements in the health of populations increases their economic productivity and prosperity. Health and economic intervention are not in conflict, but are two sides of one very large, expensive coin that is our economy.

It’s indisputable that lockdowns and other measures that have curtailed business have come at an enormous financial cost as well as other costs. However, economists say that opening the economy entirely without controlling the virus would be an unmitigated economic disaster because it would introduce overwhelming economic costs in the form of health care and lost productivity. A key goal of masking and social distancing has been to avoid this by limiting the number of cases.

Understanding this huge potential cost is important because it hasn’t been taken into account by those who advocate letting the virus run wild until herd immunity is reached in order to keep the economy strong.

Epidemiologists and economists agree on the biological fact that herd immunity will have to happen at some point for the virus to subside. That’s how epidemics end. However, they insist that control strategies to manage both the virus's spread and the economic fallout and reach as soft a landing as possible with the help of both vaccines and mitigation measures are crucial to avoid devastating long-lasting effects.

Masked people on Main Street in Park City, Utah.

The Cost of Treating COVID-19 Patients

Economists’ models showing significant differences in medical costs depending on the percentage of people who contract COVID make it clear that strategies to keep that percentage as low as possible have enormous economic value.

These models are based on methods that have proved accurate in dealing with past pandemics such as SARS. The models, published in the journal Health Affairs, indicate that a single symptomatic COVID-19 case can cost a median direct medical cost of $3,045 during the course of the infection. If 80 percent of the U.S. population got infected, that would translate to 44.6 million hospitalizations, 10.7 million intensive care unit admissions, 6.4 million hospitalizations, 10.7 million hospital bed days, and $654 billion in direct medical costs over the course of the pandemic. That figure would increase to $859.6 billion if related health-care costs for a year after people were discharged from the hospital were included. Even if the probability of severe disease leading to hospitalization was decreased by half, the costs would be still be $328.9 billion.

If 50 percent of the population got COVID, that would be 134.4 million symptomatic cases in the United States. This would cost a total of $536.7 billion, including related costs for a year after infection.

If 20 percent of the population got infected, there would be 53.8 million cases in the United States, which would cost a median of 11.2 million hospitalizations, 2.7 million ICU admissions, 1.6 million patients requiring a ventilator, 62.3 million hospital bed days, and $163.4 billion in direct medical costs over the course of the pandemic. Add post-hospitalization costs for a year and the result would be a median cost of $214.5 billion.

On average, the cost of a symptomatic COVID-19 case is more than four times higher than that of a symptomatic flu case. COVID-19 patients also have a higher probability of being hospitalized and dying than sufferers from the flu and many other infectious diseases. Studies have shown that people who have survived major complications of COVID-19 such as respiratory disease and sepsis have considerable long-lasting physical damage requiring extensive follow-up care. This can include further hospitalization.

An 80 percent infection rate would cost 18.7 percent of the total national health expenditure of $3.5 trillion in 2017, while a 50 percent infection rate would cost 11.7 percent. The difference would be $460.6 billion.

Clearly, the cost of the burden of social distancing and masks needs to be considered in the context of the alternative high medical costs associated with not using these methods.

The models take into account the different outcomes that can be associated with COVID-19, from no symptoms or a mild infection that requires isolating, telephone calls with a doctor and lost work time to the patient and those quarantined with them, to a severe infection that progresses to hospitalization and even death. Hospitalized patients have a probability of being admitted to the ICU and then of having sepsis and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) that would require a ventilator. If they survive, they could require additional post-hospital care for lingering damage for as much as a year - further hospitalizations, skilled nursing facility stays, rehabilitation stays, outpatient visits to specialists, primary care providers and occupational therapists and pharmacy costs. Costs to families whose members die or are ill for a year can escalate exponentially from there depending on the deceased person’s age and position as a wage earner or care giver.

The models are believed to underreport costs, because they include only the direct cost of the virus, not other possible related medical costs or huge productivity losses to businesses because of absenteeism, long-term COVID, and premature deaths.

Other Associated Costs

In a growing pandemic, the cost of critical medical supplies also goes up, sometimes exponentially. Other associated health care costs include reductions in elective surgery and preventive health care, which leads to worse disease outcomes down the road. Pandemic surges result in health care professionals being diverted to focus on COVID-19 cases at the expense of treating patients with other illnesses. Such deferred costs could result in an additional impact on the U.S. health system of $125 billion to $200 billion, according to a study by America’s Health Insurance Plans. The deferred cost varies by patient. A cancer patient needs to receive chemotherapy or radiation treatment promptly, so delays can impact the outcome of their cancer. Deferring treatment for a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease could increase the cost by between 7 and 11 percent.

COVID-19 also can be hugely expensive for individual patients. The median charge for COVID-19 patients without insurance or who went out of network has been between $34,662 and $45,683, according to a study by FAIR Health. Patients with insurance usually paid a maximum of $24,012, with many paying much less depending on their insurance.

Economists have a standard term called a statistical life to measure how much it is worth it economically for people to reduce the risk of mortality or morbidity. If each statistical life is worth $7 million, a conservative value, the economic cost of premature deaths expected through next year is $4.4 trillion. About a third of survivors of severe COVID-19 have some form of long-term impairment. This could affect more than twice as many people as the number who die. Respiratory complications among these survivors could cause an estimated economic loss of $2.6 trillion through next year.

Mental Health Costs

Mental health is an area where economists and epidemiologists come together to advocate a balanced and nuanced approach to virus control. The longer and more extensive the pandemic, the more mental health tolls are expected to rise, both because of anxiety over the virus and because of economic insecurity, social isolation and lockdowns. There have been reports of a 21 percent increase in medication prescriptions for depression, anxiety and insomnia.

People diagnosed with depression, anxiety, alcohol abuse, and post-traumatic stress disorder have about four times the cost of health care of people without them. At least 35 million have developed a new behavioral health problem because of the pandemic and some experts say that figure could be as high as 80 million people. This could add hundreds of billions of dollars in health care costs in the first year after the start of the pandemic. This impact is expected to continue for years after the pandemic has subsided. Treating these problems will place additional demand on the health care system.

Health Insurance Weaknesses That are Helping to Spread the Virus

The cost of COVID-19 treatment has plunged many Americans, including some who have private insurance or Medicare, into debt, with many reporting debts of more than $150,000. This cascades down to people selling their homes or dipping into retirement funds and savings to pay medical debts.

In a situation where many people have lost jobs, the typical American system of linking health insurance to employment is shaky. A lack of health insurance makes many Americans hesitant, with good reason, to be tested for COVID-19 or to go to an emergency room if they develop severe symptoms. Although the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Acts mandate free testing, many people have been charged high rates for testing done at emergency rooms or other non-public sites. Some insurance covers only tests with positive results, and the price can range from $20 to $850. Uncertainties such as this deter people from getting testing and treatment.

Those who test positive and have symptoms have the same issues that are associated with American health insurance in general. They can be charged for the services of emergency room doctors who are employed by out-of-network outside staffing agencies. One study indicated that one in five emergency room patients get unexpected bills from providers they didn’t choose. Insurers also may deny coverage of some complications resulting from COVID-19.

This is typical of American health care, but the critical difference is that people who avoid COVID-19 tests and treatment because of these issues risk not only their own health, but passing the virus on to other people.

The Broader Economic Situation

Let’s look at the broader economy. Economists say the pandemic is the greatest threat to American prosperity since the Great Depression. Its costs in mortality, morbidity, mental health and direct economic losses far exceed those from conventional recessions - four times greater than the Great Recession - and from all of the wars the United States has fought since Sept. 11, 2001. The costs are considered similar to those associated with decreased agricultural productivity and severe weather events from 50 years of global climate change.

The estimated financial cost of the pandemic because of lost output and health problems is more than $16 trillion, or about 90 percent of the annual gross domestic product of the United States, according to Harvard economist David Cutler and Lawrence Summers, who published these figures in a paper in the journal JAMA. For a family of four, that would be nearly $20,000.

More than 60 million unemployment insurance claims have been filed in the United States, including 20 weeks with a million claims per week. The Congressional Budget Office projects that the United States will suffer a total of $7.6 trillion in lost output in the next decade as a result of COVID-19. An estimated 625,000 deaths associated in some way with the pandemic are expected to occur in the United States. Major industries such as travel, trade, retail, tourism and entertainment are experiencing billions of dollars in losses.

Focused Approaches

The huge effort to develop vaccines is one of the most promising measures, and looks like it may be much more successful than had been predicted. Pfizer announced today that it expects its two-dose vaccine to be 90 percent effective in those who receive it, a much higher percentage than was expected. However, it needs to be accompanied with both the majority of the population getting the vaccine and a better approach to pandemic prevention and control. That will be costly, but nowhere near what the pandemic has cost.

Cutler and Summers recommended spending millions of dollars in focused public health approaches to prevent infection.

Traditionally, pandemic control occurs in three phases – lockdown, gradual reopening and pandemic recovery. During lockdown, efforts are made to bring down the number of cases to a controllable level. To shore up the economy during lockdown, cash transfers, unemployment benefits, support for short-time work, temporary deferral of taxes and social security payments and liquidity support for business should be forthcoming from the government. Early lockdowns worked well in a number of countries and in some locations in the United States, but other areas didn’t lock down or their citizens were less than 50 percent compliant with lockdowns. As a result of this and the nature of the virus, this stage was not as successful in the United States as it should have been although it is believed to have saved many lives.

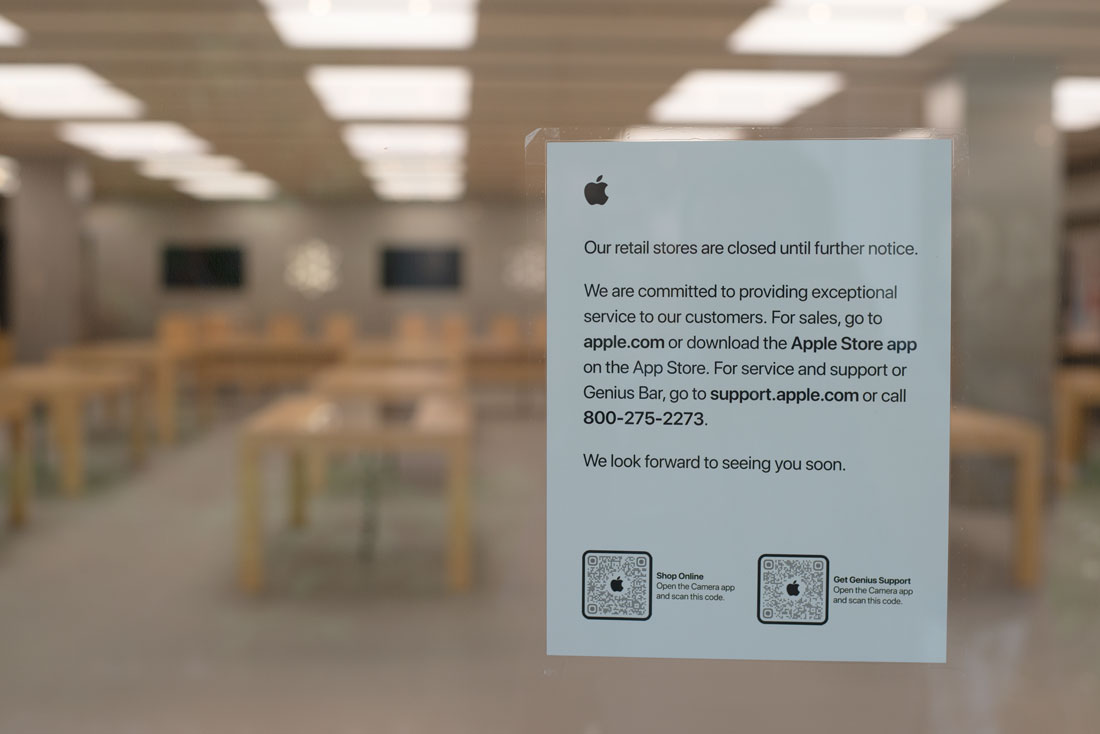

A closed Apple store during the initial lockdown. Lockdown is expensive and not effective enough if many people don't comply.

During the reopening second phase, the idea is to partially reopen with continuing social distancing, mask controls and targeted incentives focused on getting people back to work. Economists recommend that at this point, higher public investment should be made in companies with decent prospects, but there should be controls over their dividends and executive pay. This phase was attempted over the summer, but stymied by many people’s non-compliance with mask wearing and social distancing. Many epidemiologists and economists say the reopening came too soon and too drastically in many areas.

Social distancing and wearing a mask are crucial in the recovery stage to enable businesses to stay open.

The third phase, the post-pandemic period, is when reforms should be made with public investment and increased investment in not just economic recovery but also pandemic preparation to avoid a recurring surge of the pandemic. This process will be difficult and will require skilled and flexible policy making. Epidemiologists say it will be necessary for long-term control of this pandemic and prevention of other similar ones. Economists say it is well worth the required financial outlay because the economic cost of prevention, while high, is much less than the cost of dealing with a pandemic that has gotten out of control.

The Global Preparedness Monitor Board estimates that the cost of responding to the pandemic so far has been $11 trillion, with a future loss of $10 trillion in earning. Proper preparation and a quick response would have cost $39 billion. It would have taken the world 500 years to spend as much on preparedness as the world is losing because of the pandemic.

The lesson from this is that investment in pandemic preparedness, including emergency response, protecting the most vulnerable, greater support for research and quick development of vaccines and treatment, and equitable and effective distribution of them as well as sustained government leadership are crucial to controlling pandemics in the future.

High-level coordinators in various countries need to lead responses to pandemics and routinely conduct simulations to maintain pandemic preparedness. These simulations need to include decision makers, as epidemiologists have said that one of the major breakdowns in simulation exercises and training has been that while their science was sound, they didn’t take into consideration the possibility that government leaders would override them with bad decisions.

Engaged citizens will need to demand that their governments have health emergency preparedness in place and work to protect the most vulnerable within their communities. There will need to be greater coordination and support for research and development on health emergencies, including creating a sustainable mechanism to ensure vaccines and treatments are developed quickly, available early and distributed equitably and effectively.

Testing and Contact Tracing

A coronavirus test.

Epidemiologists agree that broad lockdowns are necessary amid high outbreaks to reduce mortality and prevent health care services from being overwhelmed. However, they believe that once case levels drop, the focus should change to widespread testing and tracing that detects and isolates localized outbreaks on an on-going basis.

Economics teacher Brian Bethune of Tufts University and Boston College says the cheap solution is to wear marks and socially distance during outbreaks while testing people, tracking cases and isolating the sick. Countries that went to universal mask wearing and isolated everyone who came into contact with a sick person have contained the epidemic and their briefly challenged economies have recovered quickly. The question is how much we want to pay for this pandemic. If we don’t choose the cheap solution, we will be forced into paying full price, which is enormous.

Both the economic and virus picture indicate that testing and contact tracing that reduce the virus’s early spread have massive economic value. So how much do they cost?

The cost of testing 100,000 people is about $6 million, according to Cutler and Summers. If 5,000 people, which is a conservative percentage in some areas, tested positive and at least 45 percent of them quarantined, that would translate to 2,750 fewer positive cases and at least 14 deaths prevented. The estimated economic value would be $96 million. About 33 critical and severe cases would be prevented, an estimated economic value of $80 million. Preventing these cases could lead to fewer future cases. The investment of $6 million would lead to prevention of $176 million in costs.

The Rockefeller Foundation has estimated that conducting 30 million tests weekly would cost an additional $75 billion during the next year. Adding the cost of contact tracing could cost about $100 billion, but it would be the highest return investment the government could make in light of the virus’s nature. As the pandemic recedes, testing, contact tracing and selective isolation based on them should be permanent to avoid a resurgence of it or a similar virus, economists and epidemiologist say.

Public deficits and debt will rise substantially, but economists say it is worth it to pump money into focused stimulus to prevent economies from faltering and getting caught in permanent lower growth patterns. Over time, governments can shift focus from rescuing the economy to sustainable growth. At that point, taxes may have to go up but economists say those who have prospered during the pandemic should contribute more.

Helping the Vulnerable

Half of the U.S. economy rebounded strongly as it reopened this summer and the other half continued to struggle. Overall, the economy is expected to recover normal levels of output by mid-2021. However, many individual businesses are closing and the large number of unemployed applicants is overwhelming the unemployment insurance system. Renters and landlords also are struggling. These are areas that economists say need targeted stimulus. Government policy makers are struggling to provide the relief to those who need it because they lack experience in this type of crisis.

The populations that are more vulnerable to COVID-19 overlap substantially with those that are being hit harder economically, partly because they include workers who have to do public jobs and can’t work from home and whose living situation doesn’t allow them to isolate if they are ill. Vulnerable groups include young workers; African Americans; Latinos; Native Americans and employees in industries that have been especially hard hit by the lockdowns and COVID-19 outbreaks. Women are more likely to lose their jobs than men, earn less, save less and are largely responsible for homeschooling children and caring for family members. There’s an overlap between the need to both control the virus among these groups and provide economic help to them, not an either-or conflict.

Masked people outside a restaurant in Park City, Utah. Keeping these businesses open provides jobs and income but places vulnerable workers at risk.

Conventional epidemiology suggests that protection should be focused on those most at risk from the virus while enabling children to continue going to school. This has proved difficult to manage because people of different generations live together, exposing vulnerable groups to younger groups that are mingling in society.

There are differences of opinion about how to go about focused lockdowns for vulnerable people as the world faces second and third waves of the disease. Figuring out how to do this is among the major challenges of the pandemic. Isolating at home favors the chances of wealthier better educated people who can work at home, have places to isolate and can order food delivery if they get sick. Poorer people don’t have those options, so measures need to be put in place so they aren’t at increased risk. Those measures need to include not causing breaks in the food chain that could push 135 million people into severe hunger and starvation globally by the end of the year, the United Nations Food Program says.

Social norms and an Engaged Citizenry

Pre-pandemic simulation exercises to train health personnel in controlling a pandemic didn’t take into consideration the resistance of the public to effective epidemic control.

In general, people have been very susceptible to taking unnecessary risks in a variety of settings because they lack long-term experience in coping with a pandemic. They are more likely to participate in riskier activities if other people around them are doing so. The new knowledge of the risks of the virus is competing with older established norms – congregating for social purposes, singing in church and standing close to each other when we carry on a conversation.

Some experts say the pandemic has similarities to smoking, which once was widely accepted and had a huge amount of social etiquette associated with it, but has come to be considered one of the leading health threats not just to smokers but those around them. This change in behavior lagged behind the science and health advice by years, sickening and killing many people.

People’s personal experience with COVID-19 has a huge influence on behavior, so that people from New York City and New Jersey who may have become infected or have known people who died early in the pandemic tend to support stronger controls to prevent its spread. In the absence of personal experience, people tend to fall back on clear messages from government leaders, which have been lacking in the United States and some other countries. President Donald Trump as well as some governors have played down the pandemic and Trump didn’t wear a mask in public until months after the pandemic began.

Clear messages from government leaders are important, because people depend on the government to protect them in situations where the threat is too large for them to personally understand and handle. Some epidemiologists point to the example of barriers at train crossings, which are installed because most drivers tend to misjudge trains’ speed because they lack experience with trains. People look to the government to protect them and trust it to do so in exchange for them paying taxes. Americans in general have tremendous respect for the law, to the point that many will defend a position that they personally oppose because it is legal. This makes it very important in a major crisis that they get clear information from national and state leaders as to how to function.

Psychologists say that everyone except people who suffer from clinical depression have a bias toward optimism, which normally is a critical coping mechanism to negotiate the world and make progress. When governments have optimism bias, however, it leads to bad crisis planning and decision-making. It is the government’s job to soberly sort out the data and help people understand which threats are major and which aren’t and what to do about them. People have a much stronger tendency not to believe bad news until someone in a position of authority delivers it. In the case of the pandemic, even many hospital CEOs weren’t convinced of its seriousness until the government told them. By that time, the pandemic was out of control.

The bottom line is that there isn’t a conflict between improving the economy and controlling the virus because the economy won’t recover until the virus is controlled and because the economic cost of controlling the virus is much lower than letting it run rampant. Bringing COVID-19 cases to very low levels and keeping them there also has been found to be far better for the economy than repeated lockdown and reopening cycles.

Check out these related items

Apocalyptic Outing

We take a (semi)-humorous look at what a Saturday afternoon outing is like in the fall of 2020.

Election Perspective

On a day that included both voting and getting tested for COVID-19, we look to the past for perspective on elections.

Making the Invisible Visible

The field of data-based infographics is helping the world see, understand and respond to the invisible threat of the pandemic.